The ongoing coronavirus pandemic has shaken many long-held assumptions about the Jewish community as it confronts a crisis of leadership, finance, and faith. In Queens, the divisions within the Jewish community were laid bare last Monday when Governor Andrew Cuomo declared in a press conference, “We’re going to close the schools in those areas tomorrow, and that’s that.”

His terse statement followed a phone call that he had with Mayor Bill de Blasio, City Comptroller Scott Stringer, City Council Speaker Corey Johnson, and Michael Mulgrew, the president of the city’s teachers union. Along with the closing of schools in areas designated as red and orange on the state’s coronavirus cluster map, synagogues were reduced to a minyan, with a $15,000 penalty for violating this extremely low threshold.

As a Yeshiva of Central Queens parent, I felt that my daughter’s school did everything right to comply with state guidelines, only to see the goalposts moved further away with a talking-down by the governor, speaking like a father to unruly children. Our son attends a class of six students at Positive Beginnings preschool, where it would have been easy to isolate a class with a test-positive case from the rest of the student body and faculty.

Why weren’t representatives of private schools and yeshivos on that phone call? Wasn’t it bad enough that the teachers union kept pushing off the reopening of public schools that our schools must also suffer the same consequences?

Concerning synagogues, how did a governor, who claims to be following science, decide that ten men should be the maximum capacity at any synagogue within the red zone, regardless of its size? Cuomo held a phone conference with Orthodox community leaders on Tuesday, but one Queens rabbi who was invited to participate called it a “soliloquy” where only pre-approved softball questions were heard before the operator ended the conversation.

“What Governor Cuomo did now isn’t tough love or diplomatic. It’s a blindside and likely unconstitutional,” wrote Agudath Israel board member Chaskel Bennett. “There was NO discussion of reducing houses of worship to ten today. Religious and communal leaders did NOT agree to this!”

The national Agudah filed a federal lawsuit to stop the harsh decree, with Agudath Israel of Queens Valley and Queens Jewish Link reporter Shabsie Saphirstein as co-plaintiffs. Their legal effort was shot down within two hours of Yom Tov on Friday afternoon. “How can we ignore the compelling state interest in protecting the health and life of all New Yorkers?” said Federal District Judge Kiyo Matsumoto. She held that the executive order was not targeting Orthodox Jews, and that as synagogues had complied in March, they can do so again without suffering irreparable damage.

While this judge was deliberating, Borough Park experienced violent protests, and in Crown Heights messianic Chabadniks danced in the streets on Simchas Beis HaShoeivah in defiance of rabbinic and secular authorities. As I watched social media flare up in disgust at the flagrant disregard for public health, safety, and potential backlash, I sought to express my dismay with a governor and mayor who exercised unprecedented power over our schools, shuls, and businesses, while mindful that our community has a share in the blame for the local uptick in positive cases.

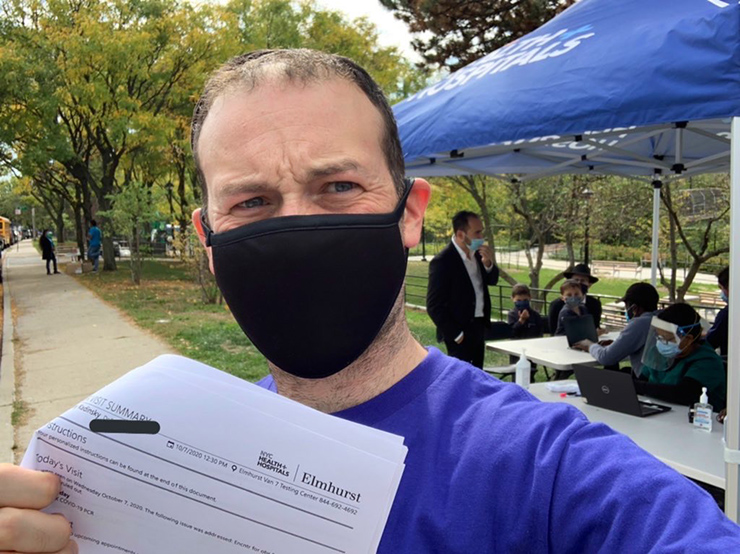

I protested on my own by making a short video statement and sharing it on social media. Bennett shared it in a tweet, and he has thousands of followers who listened to my 57 seconds describing the absurd situation where ten men sign up to daven, but only nine appear, precluding them from reciting Kaddish and leining from a sefer Torah. “Having an eleventh man here runs the risk of a $15,000 fine,” I said.

This point was also made by Tablet reporter Yair Rosenberg, who grew up in Kew Gardens Hills. “Rather than shutting them down, they need to create a pathway for these Jews to celebrate their holy day in a safe manner,” he wrote. “By working with the Hasidic communities rather than against them, and treating them as partners rather than as problems, the city can change the trajectory of this looming disaster.” Rosenberg has more than 83,000 followers reading his tweets.

For good measure, his father, Rabbi Moshe Rosenberg, published his own view of the situation in The Forward, urging compliance while expressing dismay with the guidelines. “We have the mazel to be in a red area, so now we must limit our services this Sukkos and Simchas Torah to ten people, while other, less careful synagogues will have larger services – all because of a line drawn on a map. It’s frustrating. It’s angering. It isn’t fair. But we’ll do it anyway.”

At Kehillas Torah Temimah, the online sign-up for Simchas Torah filled up within an hour of the email being sent to shul members. It was frustrating, and considering the ample outdoor space of the YCQ schoolyard, the ten-person limit made no sense.

Although my synagogue is on the red side of 150th Street, my apartment is on the orange side, where shuls are allowed a greater capacity with fewer restrictions. I took advantage of my place on the map by calling a rabbi in the orange zone. “Do you have room for one more?”

At Yeshivas Madreigas HaAdam, everyone was masked and sitting at a distance. Participants had a choice between davening indoors or outdoors. To my surprise, there was an outdoor ezras nashim and children were also invited to attend and sit with their parents. Rabbi Moshe Faskowitz, the Rosh Yeshiva, spoke in support of communities protesting the guidelines, while wearing his mask. He then had a kiddush, where the adults carefully picked their food and ate them at their seats. People socialized while keeping their distance. My wife and children had their first shul experience since Purim. Best of all, we were not breaking any laws.

After a meal at home, I took the children to Vleigh Playground, where I asked other fathers where they davened and how many people at their minyanim were wearing masks. The reality of noncompliance made for a disappointing late afternoon after the spiritual high of davening at Madreigas HaAdam.

There are still too many individuals in our community who do not take masks and social distancing seriously, while the compliant majority suffers the consequences of a shutdown. I cannot accept collective punishment as a policy, but I also recognize collective responsibility. This is why we must continue to follow the guidelines, even as we protest them.

By Sergey Kadinsky