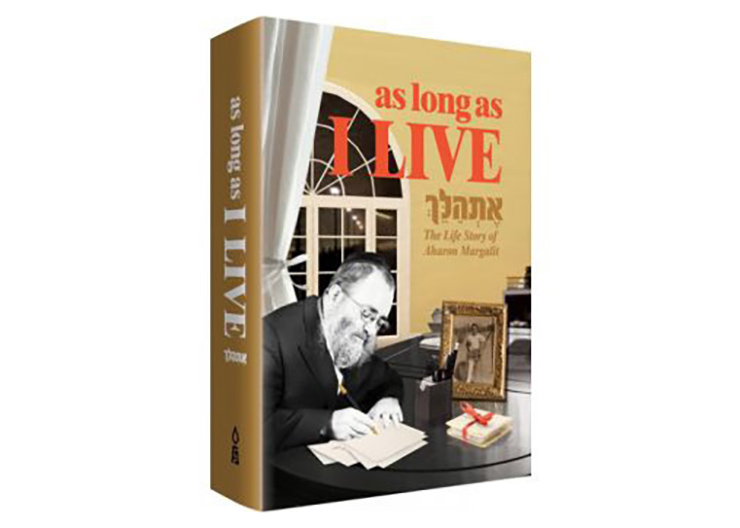

Rabbi Aharon Margalit’s autobiography, As Long As I Live, is an incredible story with many layers. This book reads like a novel with all the literary elements. The author builds the suspense, his writing voice is strong, and the descriptions of the setting are vivid and add to the story. On a deeper level, this book teaches the reader emunah and bitachon through the writer’s real-life examples. The lessons in emunah in this book are life-changing. Rabbi Margalit’s life is a lesson in believing in brachos from tzadikim, davening, and a positive attitude that Hashem is here and whatever challenge He gives us is for the best to help us grow. He shows how he learned these important lessons in bitachon from his parents, both Holocaust survivors who built a new family and life in Eretz Yisrael in a moshav after World War II. They both taught Rabbi Margalit unwavering trust in brachos from tzadikim and in Hashem’s presence in their lives. He begins the story with his early childhood, growing up on a religious moshav in Israel.

His descriptions of the moshav transport the reader there while also creating suspense. “We went to bed early, waking every morning to the sound of the roosters crowing, heralding another busy day.”

“My life stretched out before me, clear and cloudless as the blue skies that shone above on that sunny day that started out so beautifully. All I needed to make me the happiest boy on earth was a few friends and some dirt. And that’s indeed how I spent that morning: playing in the dirt, in my shorts and T-shirt, having fun. This was to be my last morning as a normal child.”

He shares how, as a small child in the early 1950s, he contracted polio, which was rampant in Israel at that time. He had to live in an iron lung, and then he was transferred to a sanatorium. He vividly describes his experience when he couldn’t move and he was in an institution with nothing to do but stare at the white walls for years. The reader is amazed at how, as a young boy, he felt no bitterness but gained maturity. It was very difficult for his parents to come visit, as it required a long bus ride from the moshav, and he understood and appreciated their effort when they could come. Shabbos was difficult, because others had visitors then, and he didn’t, and they would express pity, which really upset him.

He describes a turning point when he learned to cover himself with his blanket and thus avoid their pity, and he could use his imagination and visualization to escape to happier scenes and places. This visualization helped him later in life when a speech therapist used this technique to help cure his stuttering.

He takes the reader through his painful, arduous journey of learning to sit up and eventually to walk. He shares his thoughts and his incredible, positive, tenacious attitude that refused to accept failure or the proclamations by the doctors that he would never walk. From the beginning of the disease, when his mother went to the Belzer Rebbe for a brachah for him, this brachah stood as a shield against any negative realistic prognosis proclaimed by human doctors. The reader witnesses clearly the yad Hashem that enabled Rabbi Margalit to conquer polio. He eventually was able to walk, and he also vanquished the stutter he had developed from a childhood trauma. He takes the reader through the process and shows the reader how to tap into emunah and bitachon in the face of what appear to be insurmountable challenges.

He describes the painful experience of his bar mitzvah, when his speech impediment became like a mountain he couldn’t climb, and his embarrassment at his inability to recite a brachah in public. He shares his determination and emunah that helps him to conquer this fear and this disability to the point that he becomes a teacher and eventually a speaker.

The next challenge he faces is a frightening diagnosis of advanced stage cancer. He leads the reader through his process and the actions he takes to fight this next battle in his life. The reader goes with him to speak to the doctors to do everything humanly possible to get the best medical advice and expertise. He demonstrated how he followed his belief that “a patient must never put himself blindly at the mercy of his medical team.” He became a full partner, asking to receive all the medical information. The way he keeps fighting and doesn’t give up or surrender ever to depression or despair is so uplifting. Armed with his incredibly positive attitude, with brachos from tzadikim, and with fervent prayer, he defeats this devastating illness.

This book portrays Rabbi Margalit’s humanity, as it portrays his struggles and his times of feeling lost and discouraged, but also his ability to pick himself up in the face of so many difficulties and to rise above with iron emunah. When he received his second cancer diagnosis, he realized that Hashem had given him a mission to be in the treatment rooms, giving chizuk to others. “Here’s your task: to connect more truly with each patient, to actually feel what he’s feeling in his deepest soul: his pain, his worries, and his fears. You will tread in place of fear that threatens to extinguish every glimmer of hope.” He continues, “I will do everything I can to bring some happiness to patients in the wards, in the clinics, in the treatment rooms.” He shows how, with each difficulty, he found the mission that Hashem wanted him to accomplish. In both of his books, Rabbi Margalit teaches us that it’s not the events but our perspective – how we view those events that can bring us joy and peace of mind. “It’s a matter of making a decision. Anyone can fall into the arms of despair. But only someone who’s made a conscious decision can rise up out of the abys – in which case, even if his “wings” are punctured with IVs, nothing can stop him from soaring to freedom.” These books are so popular because we need these tools in our time more than ever.

Rabbi Margalit’s newest book, The Impact of As Long As I Live, is a follow up to his first book. It has 14 incredible stories of different individuals who used the tools and insights for life from his first book and applied them to their lives. He states in this book: “Throughout the challenges in my life, I’ve maintained the following motto – which I highly recommend to everyone: Don’t surrender to that internal voice telling you that if you feel hurt or sad or angry, it’s because of external factors such as the events and circumstances of your life. That’s a myth. I have verified the following rule hundreds, perhaps thousands, of times – and it always proves true: It all depends on a person’s perspective. In every situation, Hashem gives us the ability to choose. We can feel good or bad, we can enter a cycle of negative feelings or choose to view situations as notes from Shamayim –and then we must decipher the notes’ code in order to figure out what Hashem wants from us at that moment.

“I’ll let you in on a secret: The right answer is never ‘to be miserable,’ ‘to feel insulted,’ ‘to be callous,’ or ‘to bury myself under the covers.’ If you believe that even a seriously ill person on his deathbed still has a G-dly mission to carry out as long as he is in this world, how can it be different with regard to a person embroiled in an interpersonal crisis or any other bleak scenario? A person can always find the reason why Hashem created each particular situation. It’s not that a person can function within any situation; rather, the situation was designed with the express purpose of creating a challenge and a mission. And what are the challenge and the mission? To remember that you are master of your feelings and are therefore responsible to choose whether to wallow in misery or to forge ahead and refuse to allow the event or words to affect the way you feel…”

Both books are filled with spiritual power that will uplift the reader. In addition to the riveting story in the first book and the gripping stories in the second book, these books will gift the reader with tools and attitudes that will enhance and strengthen his emunah and bitachon.

Hashem should bless Rabbi Margalit with continued good health and strength to carry out his holy mission.

By Susie Garber