When one depicts a university, images of a campus come to mind, a cluster of buildings situated around a quad, or common green space where the disciplines interact. This plan is one of many lasting legacies of President Thomas Jefferson, who called it an “Academical Village.”

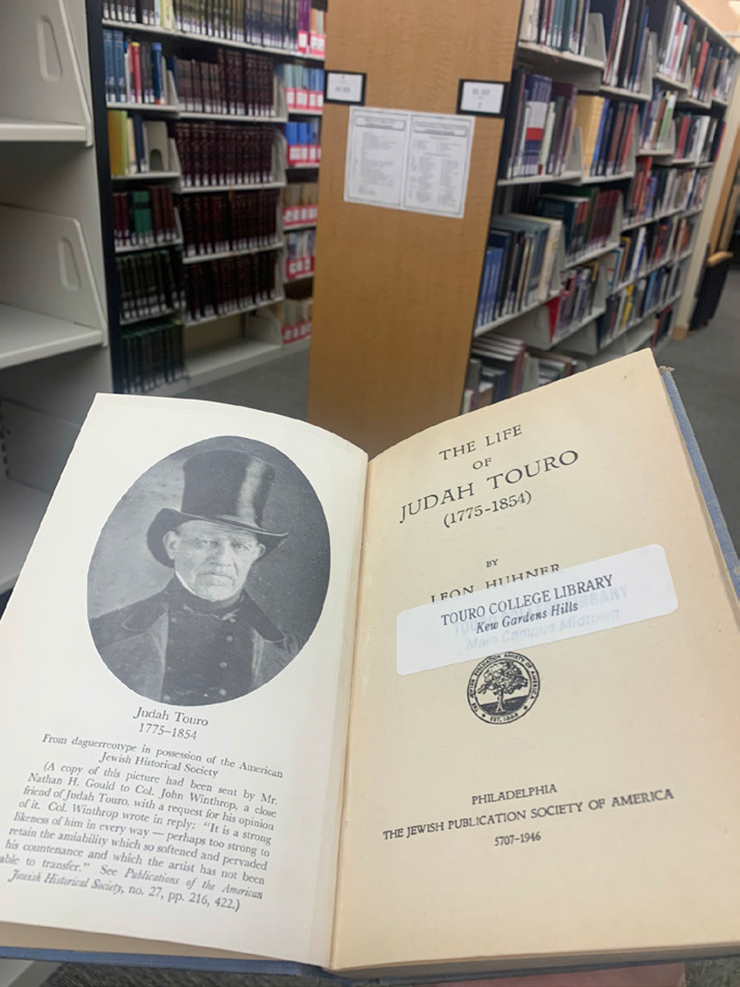

Touro University never had a central campus. From its inception in 1971, it has been an expanding galaxy of buildings sprinkled across the five boroughs, the state, the nation, and the world. Its first class in 1971 had only 35 students inside a Midtown office building, led by founder Dr. Bernard Lander. Unlike many colleges that carry the names of their founders or funders, Lander was inspired by history to name it after brothers Isaac and Judah Touro, who exemplified American and Jewish values.

The Jewish mission of Touro includes campuses in Berlin and Moscow, where there are no other colleges where Jewish holidays are respected and kosher food is served. The campus in Jerusalem offers classes in the center of the Jewish world, serving students from around the world. For an Orthodox campus environment, Lander College has separate campuses for men and women that have attracted students from across the country and abroad. For chasidim seeking to develop careers, the Brooklyn-based Machon L’Parnasa and School for Lifelong Education offer an education aligned with their values with a practical purpose.

As Touro grew from a college to a university, with branches in Nevada, California, and soon Montana, it also grew locally with beautifully designed facilities such as its Flatbush campus, the law school in Central Islip, and acquisition of medical schools that joined the Touro community. During that time, Dr. Lander never moved out of his modest house on Jewel Avenue in Forest Hills. A couple of blocks to its east is the Bnos Malka Academy, a girls’ school where two of the building’s floors host classrooms of Touro’s NYSCAS – the New York School of Career and Applied Studies.

That’s where my story at Touro College began, around the time when Dr. Lander died in 2010. NYSCAS already had a role in my family’s transition from immigrants to citizens. My mother earned her degree there and later worked at Touro as an advisor to students; my two cousins also received their degrees at Touro, and my aunt also took classes there. In high school and college, Prof. Solomon Belenky was my math tutor. He tried very hard to teach me functions, logarithms, sines and cosines, but math was simply not my strength. Rather, I was impressed by his books and poems.

His father Moisey was a Yiddish theater director and newspaper editor who was fortunate to have survived the 1949 purge of Jewish actors and poets, and later made aliyah. The son, Prof. Belensky, immigrated to New York, where he taught chemistry and math, while writing poems and tutoring students in his spare time.

After graduating from CUNY, I kept up with Belensky and also met Prof. Jacob Lieberman, who served as the director of academics at NYSCAS. When there was an opening for a history adjunct at his division, Lieberman handed me a syllabus and a textbook with the confidence that I could teach the class. With my journalism background, I was not satisfied teaching a class about the past, so I inserted news articles on how modern Egyptians felt about their ancient history, and examples of public art across the city that are inspired by the Greeks and Romans, and how they relate to their artists, locations, and the public.

In the decade since I’ve begun teaching at NYSCAS, my portfolio contains classes in Jewish history, art history, and American history. Recognizing that many colleges require a doctorate in these fields even for a part-time position, I made sure that my lessons were detailed, used credible sources, and provided practical skills to students. None of them took my classes to become art historians, but they learned how to research a topic, deliver a presentation, and understand how events and individuals changed the course of history.

This semester, one of my classes is American Cultural History, which sounds like a history class but with lessons specializing on things that were unique to this country: its constitution, flag, anthem, and innovations. In themes of three: On transportation, we began with canals, then railroads, then highways. In yeshivish parlance, highways are the avos. The tolados are drive-through restaurants, suburban development, and fast food. For sports: baseball, football, and basketball. For music: jazz, rock and roll, and hip-hop. It is as much a class in citizenship as it is in understanding popular culture. The term paper topics are chosen by the students.

“Don’t do it because it is required; do it because there’s an element of American culture you would like to know more about,” I tell them. “This is your opportunity to research it.”

The student body mirrors our diverse society. This semester I have Jonathan, a Bukharian Jew; Enkelejda from Albania; Euskadi, Mexican of Basque ancestry; Oleksandr from Ukraine; Volha from Belarus; and Christine, an African American, among others. Their term paper topics include the women’s suffrage movement, drive-in movie theaters, the transcontinental railroad, and the death penalty.

In my American Jewish history classes, non-Jewish students often sign up out of curiosity. As New Yorkers, they see Jewish culture around them. Likewise, yeshivah graduates, who previously knew nothing of Jewish history on this shore of the Atlantic, emerged with an appreciation of how this society has shaped our people, and how we contributed to it in return.

My class serves as their introduction to Haym Solomon of the American Revolution, Judah P. Benjamin and Joseph Seligman of the Civil War, the labor movement, Meyer Lansky, the rise and decline of Reform Judaism, and the revival of Orthodoxy.

Looking ahead, I am expanding my portfolio with a proposed class in Eastern Jewish topics, stories of communities outside of the Ashkenazic and Sephardic experience, such as the Jews of China, India, Ethiopia, Iran, and Bukharian Jews. The majority of Jewish students at the NYSCAS Forest Hills campus come from the latter category. Thanks to local rabbis, yeshivos, and kiruv organizations, most of them are religiously observant. But as most books on Bukharian Jews are written in Russian or Hebrew, the English-speaking youth know how to put on t’filin and keep kosher, but are not aware of their history, language, and ancestral lands.

This class explains how their ancestors arrived in Central Asia, how their traditions developed, how they maintained their identity during the Muslim, Russian, and Soviet periods, and what inspired them to immigrate en masse to America and Israel. With many years of experience translating Bukharian writings to English, I look forward to sharing them with my students.

As Touro University expands its global footprint, so have my lessons. At the same time, as Dr. Lander lived in his home on Jewel Avenue, my classes also feature a local angle that relates to students of the surrounding communities.

While Touro has its historic dinner on Monday, December 5, honoring its President Dr. Alan Kadish, board member Dovid Lichtenstein, Vice President and Dean Dr. Robert Goldschmidt, Vice President Shelley Berkley, and honorary doctorate recipient Dr. Albert Bourla of Pfizer, I have my own personal list of honorees. They entrusted me to deliver lectures with confidence in my teaching abilities and encouraged students to sign up for my classes.

They are the late Prof. Belenky, Department Chair Dr. Jacob Lieberman z”l, my mother Galina Kadinsky z”l, Art Department Chair Atara Grenadir, Site Director Naum Volfson; Profs. Richard Niness, Howard Feldman, and Ronald Brown; Tatiana Portnova and Laura Rusakova, among others. As they read this column, I thank them for their support and advice over the years.

By Sergey Kadinsky