On Yom Kippur in 1967, thousands arrived at the Western Wall for the concluding prayers and to hear the long-awaited sound of the Shofar.

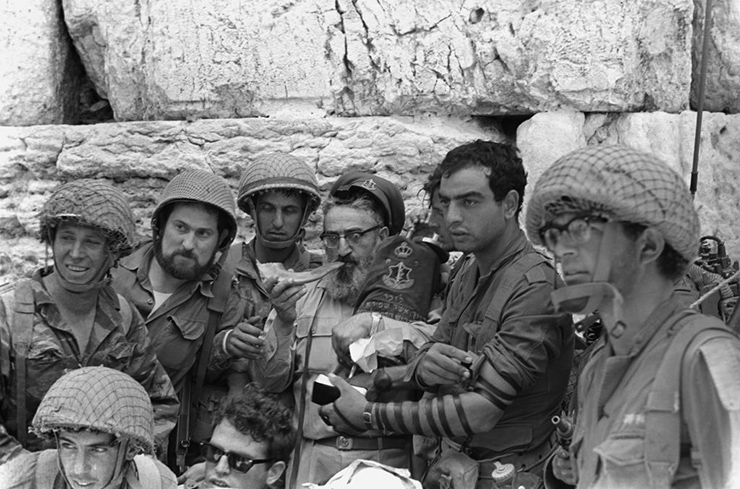

Prior to the advance of Israeli paratroopers into the Old City of Jerusalem in June 1967, during the Six-Day War, the Western Wall area had occupied a narrow space between houses just a few yards away, which restricted the size of the crowd. The Jewish presence there was also subject to intermittent restrictive regulations.

The 20th century was a transitional time for the Land of Israel, and the Western Wall was under many rulers from the Ottoman Turks to British Mandatory rule to the Jordanians - and then Israel.

Yom Kippur of 1929 followed the devastating pogroms in the land of Israel. Death and destruction were incited largely by the vehement anti-Zionist Mufti of Jerusalem, Amin Al-Husseini. In the aftermath, British authorities allowed the mechitzah (dividing screen between men and women) at the Western Wall, which was prohibited the prior year, but the sounding of the Shofar was now prohibited, due to pressure from the Mufti and his cohorts. That decree remained in effect through the duration of the British Mandate.

Despite the restrictions, the sounds of the shofar were sounded at the conclusion of Yom Kippur in accordance with tradition and as an act of defiance against British rule. Most of the “perpetrators” did not manage to elude authorities. They were swiftly arrested and given prison sentences, up to several months.

At the conclusion of Yom Kippur 1947, just two months prior to UN Resolution 181 partitioning Palestine into a Jewish and Arab state, and less than one year before the establishment of the State of Israel, seven youths were arrested and imprisoned without trial at the Latrun Prison.

The independent State of Israel was declared on May 14, 1948, and was preserved only through desperate defense from the invasion by five Arab nations. But valiant efforts to hold on to the Old City did not succeed and it fell to Jordanian forces. The Western Wall was then declared off-limits to Israelis by the ruling Jordanians. The State of Israel arose, but the Old City of Jerusalem was devoid of its age-old Jewish population. Visits to the Western Wall by non-Israeli Jews were restricted.

For the next nineteen years, the Western Wall remained off-limits. When Yom Kippur arrived, it stood in solitude, devoid of its faithful. Jews could only gaze from afar from the Israeli side of the armistice line.

However, that would soon change.

Upon the victory of Israeli forces in the 1967 Six-Day War and the liberation of the Old City of Jerusalem, the Jews once again had access to the Western Wall. That Yom Kippur, thousands arrived to the recently expanded Western Wall plaza to pray.

As the concluding neilah prayers began, the crowd had grown to 10,000.

Many had arrived to participate in the concluding prayers and to hear the sounds of the once-forbidden shofar at the end of the holy day. Joining in attendance were Knesset members, rabbis, and the mayor of Jerusalem.

As the neilah prayer concluded, the blast of the shofar was sounded by Rabbi Moshe Segal who, in 1930, was the first Jew to defy the British ordinance. The crowd burst out, singing the prayer, “Next Year in Jerusalem,” which immediately follows the neilah service.

After the conclusion, the crowd in unison began chanting “HaTikvah,” the Israel national anthem, and then “Ani Maamin” (I believe), the statement of faith as enunciated by Maimonides on the eventual arrival of the Mashiach. It was a declaration for the present and a prayer for the future. Despite the crowning achievements of the recent past, prayers were also offered for the ultimate fulfillment of Jewish destiny-the complete redemption of Jewry.

Over the centuries, Jews could only dream of the observing Yom Kippur like that of 1967 at the Western Wall.

By Larry Domnitch