As we begin the new Torah cycle, let’s take a moment to contemplate the deeper purpose of Torah. Some may refer to the Torah as a history book; others may think of it as a book of law or a source of Jewish wisdom. While these are all true, they only scratch the surface of the Torah’s true nature.

Torah is not simply a guide to living a life of truth within this world; it is the blueprint and DNA of the world itself. Our physical world is a projection and emanation of the deep spiritual reality described in the Torah. This is the meaning behind the famous Midrash: Istakel b’Oraisa u’bara alma — “[Hashem] looked into the Torah and used it to create the world” (Bereishis Rabbah 1:1). Torah is the spiritual root of existence; the physical world is its expression.

Imagine a projector: The image that you see on the screen emanates from the film in the projector, so that everything you see on the screen is simply an expression of what’s contained within the film. So too, every single thing that we see and experience in the physical world stems from the spiritual root — the transcendent dimension of Torah. To illustrate further, the trees you see outside originally stemmed from a single seed. Similarly, each and every one of us originated from a zygote, half a male and half a female genetic code. From that single cell ultimately manifested a fully developed and expressed human being. You are the expression of your original seed, just like the world is the expression of its original seed and root — the Torah. Thus, the world in which we live is an avenue to the spiritual; we can access the spiritual, transcendent world through the physical world because the two are intimately and intrinsically connected.

To relate to this concept, think of the way in which other human beings experience and understand you. All they can see of you is your physical body. They cannot see your thoughts, your consciousness, your emotions, or your soul. All they can see are your actions, words, facial expressions, and body language — i.e., the ways in which you express yourself within the world. They cannot see your inner world, but they can access it through the outer expressions that you project. The same is true regarding human beings trying to experience Hashem and the spiritual. We cannot see the spiritual; we cannot see what is ethereal and transcendent, only that which is physical. However, we can use the physical to access the spiritual; we can study the Torah’s expression in this world to understand its spiritual root.

To fully grasp the depth of this concept, we must understand the nature and purpose of a mashal. A mashal is an analogy, an example one gives in order to explain an abstract, conceptual idea to one who does not yet understand it. If a teacher wants to share a deep principle with his or her students, they might share a story or analogy that depicts the idea through a more relatable medium. While the mashal does not fully convey the idea itself, it leads the listener toward it, aiding him or her in the process of understanding. Deep ideas cannot be taught, as they are beyond words. They can only be hinted to and talked about. The job of the teacher is to guide the student toward the idea until the idea falls into the student’s mind with clear understanding. A mashal serves as a guiding force in this process, leading the student toward an understanding of that which defies simple explanation.

This process itself can be understood through a mashal. You cannot teach someone how to ride a bike. You can only help them, holding on while they practice, and perhaps showing them an example of how it is done. Ultimately, though, you must let go, and the student will have to learn how to ride independently. (This is a mashal to help explain the concept of a mashal. Think about that.) Once you learn how to ride a bike, it’s hard to imagine not being able to ride one. We often can’t understand what took us so long to learn. Yet, despite the fact that we now know how to ride a bike, we will not be able to explain how to ride a bike to someone else. It is simply beyond words.

A mashal is the only tool a teacher can use to teach spiritual truths; the learning and understanding must be done within the inner mind of the student. If this is true, how can we relate to and understand the spiritual world? We cannot see, touch, or feel the spiritual. Thus, if all learning occurs through the use of analogy, what mashal did Hashem give us to help us access spiritual truths?

The ultimate mashal is the world itself. The physical world guides us toward deeper, spiritual truths. Everything in this world is a mashal — a tool guiding us toward a deeper reality. Every physical object, every emotional phenomenon, every experience in this world is part of a grand mashal leading us toward the root of all existence. With the Torah as our guide and teacher, we can navigate the physical world and understand how to trace ourselves back to our ultimate Source: Hashem.

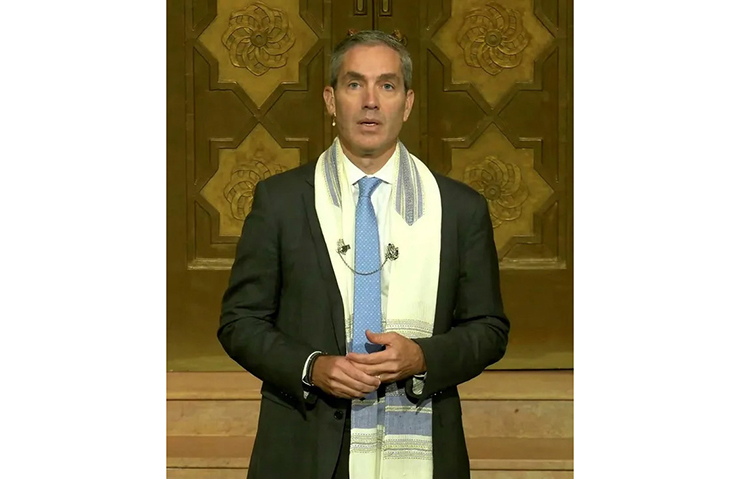

And as we begin the new parsha cycle, I invite you to get a copy of my parshah sefer, The Journey to Your Ultimate Self, and take this journey with me into the deepest and most inspiring ideas of Torah thought. This sefer serves as an accessible and inspiring gateway into deeper Jewish wisdom, living a life of higher truth, and achieving your ultimate purpose. It is organized according to the weekly parshah, providing a consistent framework for learning and spiritual growth. The ideas in this sefer are rooted in the full range of Torah wisdom, spanning Tanach, Gemara, Midrashim, and the writings of classical Jewish thinkers, including the Maharal, Ramchal, Nefesh HaChaim, R’ Tzadok, and Sfas Emes. Each chapter concludes with a summary to help you remember the main concepts and ideas, as well as action points and discussion questions to help close the gap between intellect and action. I can’t wait to embark on this journey with you as we continue journeying to our ultimate selves!

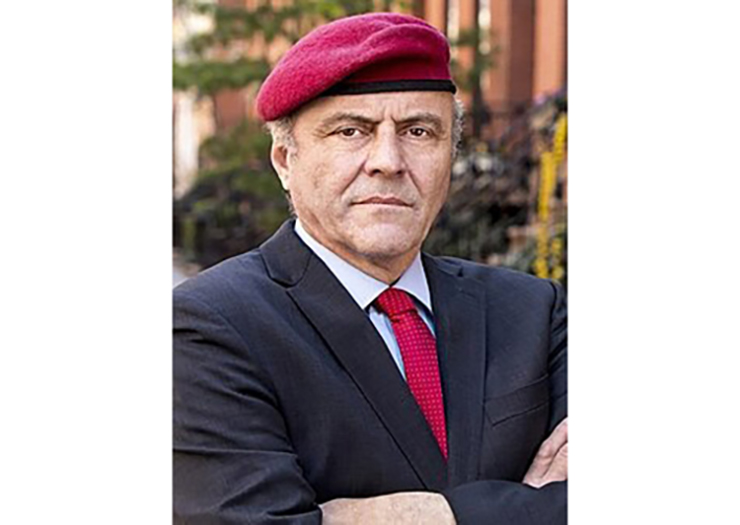

Rabbi Shmuel Reichman is the author of the bestselling book, The Journey to Your Ultimate Self, which serves as an inspiring gateway into deeper Jewish thought. He is an international speaker, educator, and the CEO of Self-Mastery Academy. After obtaining his BA from Yeshiva University, he received s’micha from RIETS, a master’s degree in education, a master’s degree in Jewish Thought, and then spent a year studying at Harvard. He is currently pursuing a PhD at UChicago. To invite Rabbi Reichman to speak in your community or to enjoy more of his deep and inspiring content, visit his website: www.ShmuelReichman.com.