Recently, I came across a word I was unfamiliar with: defenestrate. I had to look up the definition to find out that defenestrate means to toss out of a window. I’m not really sure why throwing something/someone out of the window needs its own word. Just say it was thrown out of the window. But then there are many strange things about the English language.

I found that the word originates from two incidents in history, both occurring in Prague. In 1419, seven town officials were thrown out of a window in its New Town Hall, precipitating the Hussite War. In 1618, two Imperial governors and their secretary were tossed from a window in the Prague Castle, sparking the Thirty Years’ War. The incidents were referred to as the Defenestrations of Prague.

The truth is that a far earlier defenestration is mentioned in Sefer Melachim (II 9:30-33) when Yehu ordered the evil Queen Izevel to be defenestrated, killing her.

Apparently, I am not the only person who found the word amusing. The English poet RP Lister wrote a poem called “Defenestration”: “Why, then, of all the possible offences so distressing to humanitarians / Should this one alone have caught the attention of the verbarians?”

I’m sure it’s no coincidence that the Yiddish word for window is fenster.

When I shared the word with my family, I knew immediately what it would remind them of. Several years ago, one of our children – who shall remain nameless – went to the bathroom in the middle of the night. Just then, the alarm on a watch belonging to one of his siblings began beeping. In his half-asleep state, he could not figure out how to turn off the alarm. As the beeping relentlessly continued, he did what any other thinking person would do: He opened the bathroom window and chucked the watch out. (No, it was not because he wanted to see time fly.)

We found the watch the following day on the ground outside, decimated when it was defenestrated.

We state every day in P’sukei D’Zimrah that Hashem “heals broken hearts and dresses their wounds.”

It’s notable that the pasuk doesn’t say that Hashem removes wounds and broken hearts, but that He heals and dresses them. Whenever we are placed in a challenging situation, it forces us to draw on inner capabilities and strengths we may have been previously unaware of.

In Parshas VaYishlach, when Yaakov Avinu went to retrieve small jugs from across the Yabok River, he encountered an angel with whom he struggled throughout the night. The Rashbam explains that the angel came to stop Yaakov from escaping, to ensure that Yaakov would remain to face Eisav, so that Yaakov would experience great salvation. According to the Rashbam, Yaakov Avinu wanted to escape the cause of his fear and had to be divinely restrained from doing so.

After a challenge has passed, we need to remember it, so we can hold onto the growth we gained from the experience.

In recent years, there has been much discussion in the world of psychology about a phenomenon called Post-Traumatic Growth. It is when negative experiences spur positive changes, including recognition of personal strength, exploration of new possibilities, improved relationships, a greater appreciation for life, and spiritual growth. Many people who have endured war, natural disasters, bereavement, job loss and economic stress, serious illnesses, and injuries find that they have become better people as a result. Despite the trauma of their experiences, which must be dealt with, there is also a silver lining of personal growth.

We do not move on from challenges and tragedy. Rather, we seek to move forward.

That is why Hashem doesn’t remove our wounds, but rather dresses them with bandages to help them heal. Scars can become proud symbols of growth and maturation.

Life often settles into routine, and we proceed on autopilot. Then, suddenly we are faced with an unexpected challenge or difficulty that jolts us out of our routine. Those are the unwelcome alarms that ring.

If it were up to us, we would defenestrate our troubles. But doing so would rob us of the growth that inevitably occurs. It may not be pleasant, and it surely isn’t welcomed. But, amazingly, afterwards many people assert that they wouldn’t trade the experience.

One of my teachers shared a great quote: “The only way out is through.” That doesn’t mean that the only way out is by defenestrating. Rather, the only way to deal with our troubles is to face them to the best of our ability.

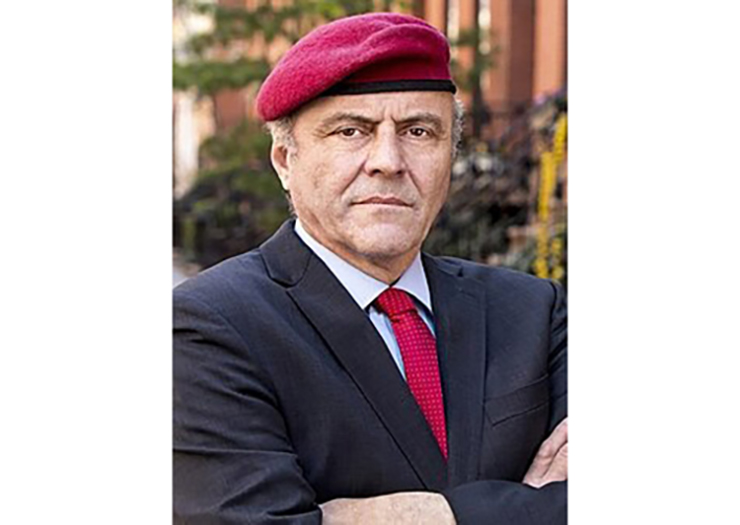

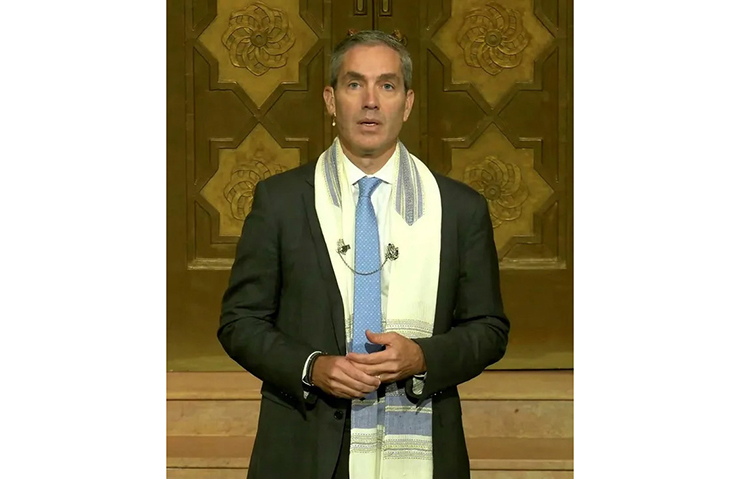

Rabbi Dani Staum, LMSW, is a popular speaker, columnist, and author. He is a rebbe at Heichal HaTorah in Teaneck, NJ. and principal of Mesivta Orchos Yosher in Spring Valley, NY. Rabbi Staum is also a member of the administration of Camp Dora Golding. He can be reached at This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it. and at www.strivinghigher.com