On the morning of the fast of Asarah B’Teves a few weeks ago, I wanted to speak to my ninth-grade class about the reason and significance of the fast. I began by asking them, “So, what sad event happened today?” One of my students explained that the previous night during an NFL game between the Buffalo Bills and the Cincinnati Bengals, Damar Hamlin of the Bills went into cardiac arrest and had to be resuscitated on the field before being rushed off to the hospital.

That wasn’t quite the tragedy I was referring to.

Nevertheless, it is worth noting that Hamlin’s injury was a major national event. The fact that it had occurred in front of thousands of people, in the middle of a game after a routine tackle, added to the shock it sent to the NFL faithful. Some players were in tears while others walked around dazed afterwards. The game did not resume.

As of this writing, Hamlin has been making an astounding recovery.

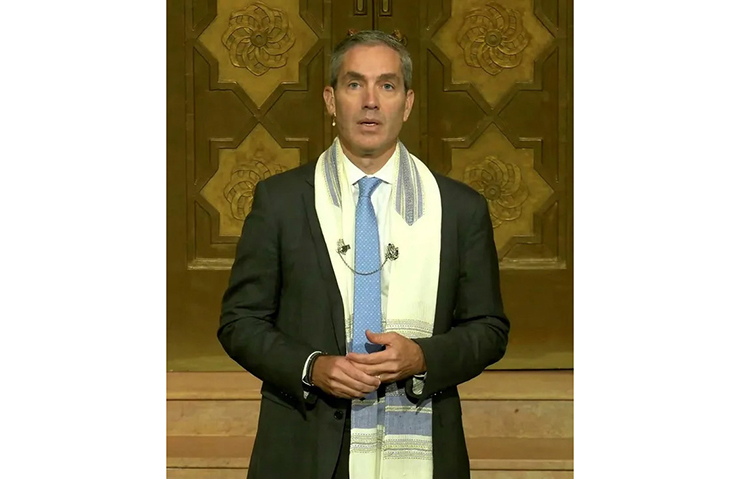

A few days after the event, while the incident was being discussed on ESPN’s show “NFL Live,” Dan Orlovsky, a football analyst, interrupted the show to offer a 50-second prayer to G-d. He did not use terms like a “higher power” or a “greater force.” He did not suffice with the general statement of our “thoughts and prayers are with him.” He went all in. He stopped the show, acknowledged G-d, closed his eyes, bowed his head, and led a full-fledged prayer session in the middle of a sports show on national TV.

It was a daring move and one that easily could have cost him his job. Our society has sought to undermine G-d and prayer, even abolishing it from our public schools. Surprisingly, the reaction to Orlovsky’s prayer was positive. In fact, it has been described as one of the “most powerful TV moments ever.”

For us, as believing Jews, prayer is a cornerstone of our faith. In fact, the two are synonymous – Jew and prayer.

Rabbi Shabtai Yudelevich (Drashos HaMagid 1) recounted a story that appeared in the secular newspapers. It was about a seven-year-old boy from Bogota, Colombia. His parents were so destitute that they couldn’t provide for his basic needs. They left him on someone’s doorsteps, hoping that he would be cared for there.

Although the boy was taken in and his basic needs were cared for, he missed his parents terribly and wanted to be reunited with them.

The boy wrote a letter...to G-d. He wrote about how painful and difficult things were for him, and how badly he wanted to go home. He asked G-d to give his parents the money they needed to care for him and to help him find them. The boy addressed the envelope to G-d and dropped it in the mailbox.

When the letter arrived at the post office, it was brought to the director of the post office. Not knowing what else to do, he opened and read the letter and concluded that it was written with sincerity. He decided to try to track down the author of the letter so they could help him.

After a long search and much advertising in local papers, they discovered who the child was. They helped the parents purchase a home and reunited the boy with his parents.

Afterwards, the director asked the boy why he hadn’t written a return address on the envelope. The boy replied honestly that he didn’t think to do so because G-d knows where he lives.

Rabbi Yudelevich concluded that we don’t need to write letters to G-d. Every sincere prayer we utter is accepted from wherever we are, as long as we call out faithfully.

Rabbi Shimshon Pincus noted that to daven to Hashem and have one’s prayers heard doesn’t require that one be righteous. At the same time, even a sinner should never assume his prayers won’t be accepted. There is only one requirement for prayer – that one call out to God with sincerity and faith. “Hashem is close to all those who are close to Him, to all those who call out to Him with sincerity.” The goal of prayer is that we should feel like we have an ongoing and deep connection with G-d.

In Parshas B’Haaloscha, when Hashem chastises Aharon and Miriam for speaking unbecomingly about their brother Moshe, Hashem states, “My servant Moshe, in My entire House he is a ne’eman.” Ne’eman is loosely translated as trustworthy or faithful.

Ibn Ezra comments that a ne’eman is like a ben-bayis, a quasi-resident of a home, who enters whenever he wants, even without prior permission, and feels comfortable to speak his mind if he needs or wants anything.

Growing up, my neighbor Eli was a ben-bayis in our home. He would pop in literally whenever he wanted, shmooze with whomever from the family was around, take snacks from our cabinet, and enjoy whatever book or gadget he found. My family loved his visits and appreciated the fact that he could come and go as he pleased and truly feel at home.

There is a certain endearment with having a ben- (or bas-) bayis who has that feeling of comfort.

A Jew is supposed to feel that he is a ben-bayis of Hashem, in the sense that he is comfortable turning to Hashem in prayer whenever and wherever. He doesn’t have to wait for times of prayer or for when he is in a shul. Beyond set times and places of prayer, he knows that G-d is never out of earshot. On the way into a meeting, on the way to work or school, or on the way home, he is constantly praying to G-d for assistance and guidance. He knows that he and his prayers are always welcome.

Prayer is not limited to times when someone is in cardiac arrest or other moments of crisis. Prayer is foremost about connection. In the words of David HaMelech, “I love that Hashem hears my voice, my supplication – that He inclines his ear to me, and in my days I call.” When it comes to prayer, a Jew should always feel at home.

Rabbi Dani Staum, LMSW, a rebbe at Heichal HaTorah in Teaneck, New Jersey, is a parenting consultant and maintains a private practice for adolescents and adults. He is also a member of the administration of Camp Dora Golding for over two decades. Rabbi Staum was a community rabbi for ten years, and has been involved in education as a principal, guidance counselor, and teacher in various yeshivos. Rabbi Staum is a noted author and sought-after lecturer, with hundreds of lectures posted on torahanytime.com. He has published articles and books about education, parenting, and Torah living in contemporary society. Rabbi Staum can be reached at This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.. His website containing archives of his writings is www.stamTorah.info.