This Yom Kippur marked fifty years since the tragic war that broke out on Yom Kippur in 1973. Fifty years is a significant time - half a century, to be exact. A jubilee according to the Jewish calendar. A lot has changed since; however, many of the changes we are experiencing today started as a result of the Yom Kippur War. This includes the disastrous Oslo Accords, or rather the Oslo Surrender, which took place exactly thirty years ago, and also the recent turmoil and waves of civil violence waged by a progressive minority that are bringing Israel on the cusp of civil war.

The Yom Kippur War was a critical turning point in the history of the State of Israel. Though Israel defeated several armies in a matter of six days during the historic Six-Day War in 1967, in 1973 things looked dismal for the State of Israel. Along the many planning failures at the military and home front levels, came the death of David Ben Gurion, the first Prime Minister of Israel.

In 1967, the majority of the ruling elite of the country was blind to Hashem’s hand in the miraculous victory and defeat of four enemy armies. They would just not hear of it. Ezer Weizman, the Deputy Chief of Staff at the time, proclaimed that the next war “would be over in six hours.”

In the aftermath of June 1967, Israel suffered from “la folie de grandeur,” or overconfidence. One compelling set of explanations can be found in the Nobel Prize-winning research of two psychologists who identify ways in which the human brain is hard-wired to systematically err by relying on mental shortcuts over “rational,” probabilistic judgment under certain conditions. Incidentally, these psychologists, Daniel Kahneman and Amos Tversky, were Israelis who left their academic posts in America to serve in the 1973 war. Research shows that feelings of confidence do not necessarily correlate with accurate judgments. “Organizations that take the word of overconfident experts can expect costly consequences,” writes Kahneman, adding, “An unbiased appreciation of uncertainty is a cornerstone of rationality—but it is not what people and organizations want.” Unfortunately for Israel, its generals in 1973 were uninterested in uncertainty. As some of them testified after the war, “The best support that the head of military intelligence can give the chief of staff is to provide a clear and unambiguous assessment . . . the clearer and sharper the estimate, the clearer and sharper the mistake—but this is a professional hazard.”

“The Blunder,” as the Yom Kippur War came to be known in Israel, was not merely an intelligence failure, but also a failure of preparation. The Israelis were wildly outnumbered on both the Sinai and Golan, and not entirely for lack of resources. Rather, Israel’s stunning victories against Arab forces in 1948, 1956, and 1967 had produced among its leaders an impression of Israeli military superiority and of Arabs as poor fighters. Chief of Staff Gen. Elazar summed up this dynamic when he told his staff, “We’ll have one hundred tanks against [Syria’s] eight hundred. That ought to be enough.”

Everything changed in the aftermath of the heavy casualties of the war and with the death of Ben Gurion for the secular citizens of Israel. Ben Gurion and Theodor Herzl were secular Jews, yet they had messianic qualities. Herzl’s bar mitzvah sermon was all about the commentaries and the interpretations by Rav Judah Alkallai on the Torah subject of the week. Rav Judah Alkallai had a deep influence on Herzl’s grandfather which trickled down to Herzl’s consciousness even though he was assimilated at the practical level of Judaism. Ben Gurion made sure to gather the Jews spread across North Africa and the Middle East and brought them to Israel. Ben Gurion declared as follows: “I am a Jew first, and only then an Israeli. The thing that sustained the Jewish people throughout the generations and led to the creation of the state was the Jewish vision of the prophets of Israel, a vision of Jewish and human redemption. The State of Israel is now an instrument for the fulfillment of this messianic vision.”

As a result of the near-defeat during the Yom Kippur War and following Ben Gurion’s death, the idea of the new Jew that Ben Gurion wanted to create became questionable to the seculars. Many seculars questioned their presence in the land of Israel, and the need for a state altogether. Suddenly, the new Jew is no longer a strong soldier and its motivation to defend its land is dissipating. They suffered a real pogrom in their new country. The new Jew has a low morale, can’t relate to his brothers that have Middle-eastern roots, and now accepts the dictates of the world and aligns himself according to the pressures that are exercised upon him. He questions his rights to the land of Israel. Some of them even prefer to destroy the state than to see it become more faithful and traditional.

This is how the Peace Now movement was born, which then gave birth to Oslo, and then to the disastrous withdrawal from South Lebanon, which was followed by the unilateral retreat from Gaza, which have brought Hamas and Iran to Israel’s doorstep. Moreover, the dangerous gambles taken by various governments and the defeatist mindset that have taken over Israel’s military and foreign policy have turned Israel into crisis after crisis, where difference of opinion is a reason for deep hate and animosity among fellow Jews. Israel, as a result, is unable to detangle itself from the aspirations of sovereignty by a terror entity inside its borders. This most corrupt and anti-Semitic entity has been created by the defeatist mindset of the new Jew that came forth in the aftermath of the Yom Kippur War through its own policies. But it got worse. On the domestic front, Israel is now a country were at anti-government demonstrations citizens call elected officials, including its Prime Minister, “Nazis” - and go unpunished. A political debate about judiciary reforms has become a platform for elitist pilots to turn their F-16s against their own country by refusing to serve if and when called upon. Moreover, Jews with a kippah and beard are no longer safe in the streets of Tel Aviv. If Israel was located in Europe, it would be the most anti-Semitic country.

How a country such as Israel has turned into one that can turn ordinary citizens in repeat violent mobs is best explained by Mattias Desmet, the brilliant Belgian expert on the theory of mass formation, in his work “The Psychology of Totalitarianism.” When people lose their sense of purpose and freedom as many in Israel sadly have, as a result of their lack of belief and understanding as to why they as a people have a right to an independent country, they become captive to the grips of mass formation - a dangerous, collective type of hypnosis that forbids dissident views and relies on destructive groupthink.

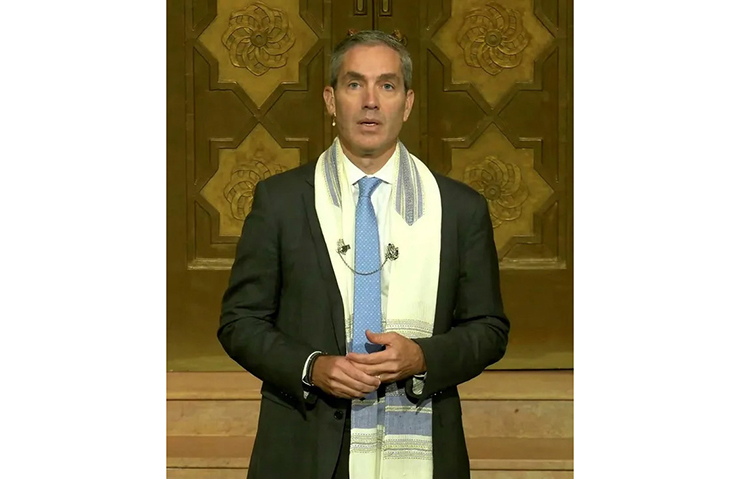

Twenty years after the Yom Kippur War, I had he immense privilege to commence my advanced Judaic studies in the Yeshivat Hesder of Ma’aleh Adumim, which was founded by Rav Chaim Sabato.

“The one thing I was certain of was that the world would never be the same.” Twenty-one-year-old Chaim Sabato goes to the battlefront in the Yom Kippur War, brimming with confidence. Israel had defeated the Syrian army in just six days a few years earlier, he had gotten a blessing the previous night from an elderly Chassidic Rebbe, and he was traveling together with his childhood best friend and study partner, Dov Indig. Chaim expects everything will follow according to plan; the good guys will win, the righteous will be protected, and he and Dov will continue to study Talmud and Tanach together. In Adjusting Sights, published in 1999, Sabato relates what happens next.

As Dov and Chaim arrive in the Golan, panic and disorder meet them at the door of their bus. Even though they had always been in the same tank, desperate and unprepared commanders were grabbing soldiers right off the buses, adding them to makeshift crews. Chaim goes with one crew, Dov with another, and enters one of the most violent tank battles in the history of warfare. Chaim’s crew is saved from certain death at the last moment, but Dov never returns from battle.

The rest of the book is filled with Chaim’s singular quest to find out “what happened to Dov?” Chaim has lost his best friend, and in his grief, he searches for a way to reconcile his own optimistic faith with an ugly world that has detached itself from G-d – one that can instantly claim the life of a righteous man like Dov.

I read Adjusting Sights during a painful period in my own life, after the loss of friends during the Second Lebanon War and again after the loss of my mother this past year. The year of mourning for the loss of my mother was when all chaos erupted in Israel, and when I started to ask, “What happened to our beloved State of Israel?” It was and remains a frightening period for the Jewish people in Israel and worldwide. An Israel that detaches itself from G-d is going against its nature, and a country that goes against its nature has no merit.

Let us hope that fifty years later we remember the sacrifice of the over 2,400 holy soldiers who faced death in their eyes and fell to defend our land and our people. Yom Kippur is when Jews confront the Angel of Death. As we look forward to the coming year, we are uncertain what our fate will be. To emphasize this, we read the words of the Unetaneh Tokef prayer: “Who will live and who will die... who by water and who by fire, who by sword and who by beast, who by famine and who by thirst…” And at that very moment, we think about our death. Franz Rosenzweig notes that the kittel, the white coat worn on Yom Kippur, is intended to be a dress-up of the burial shroud, because the purpose of Yom Kippur is to have everyone roleplay their death, by fasting and abstaining from physical pleasures. There are times when we all must turn to death before turning back to life.

When the book of death is open, one immediately understands what a privilege it is to be inscribed in the Book of Life. May we all also recognize the privilege to live in times when we have a Jewish country. May we mortals be able to set our differences aside for the sake of seeing our beloved State of Israel live forever, for our future generations.

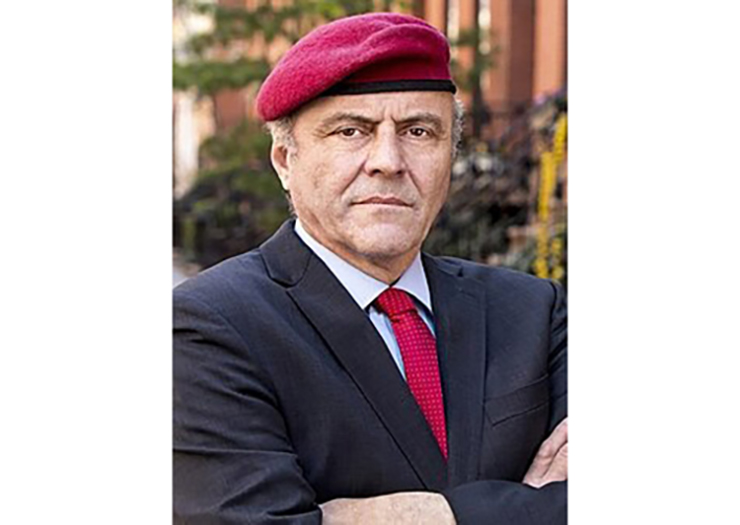

By Jacques R. Rothschild