In the town of Halberstadt, Germany, over 100 years ago, lived the gaon, Rav Binyamin Tzvi Auerbach zt”l. He grew up in France and served as a rabbi in Darmstadt for ten years after earning s’michah as well as a PhD in philosophy and Semitic languages. While living in Frankfurt, Rav Auerbach wrote the sefer Bris Avraham in memory of his father, and also spent much of his time editing Sefer HaEshkol, written by the Raavad of Norvona in the 13th century. Years later, when he became the Rav of Halberstadt, he published his work as a commentary named Nachal Eshkol.

Rav Auerbach was well respected by the Jewish community, as well as the local authorities, and was called upon time and time again to intercede with various agencies in times of crisis. His dignified manner, and his ability to converse with the gentiles on many differing topics, endeared the rabbi in their eyes. This came in handy on more than one occasion.

A Jewish child was kidnapped from his family and taken in by a nearby monastery. The priests and nuns did their best to brainwash the child and uproot any semblance of Judaism, and to a large extent, they were successful. The child became a practicing Christian, and studied diligently to understand the ways of the Church. However, the Jewish parents mounted a herculean search and rescue effort and although it took a number of years, they finally tracked down their child.

Finding the child was the easy part. The monastery adamantly denied any involvement in a kidnapping scheme, and objected vociferously to harboring a Jewish child against his will. Both sides hired legal representation, and the matter was brought before a magistrate to determine the facts. First the parents tearfully pleaded their case, detailing how their little boy was snatched away from his home and his family, and how it took much time, effort, and money to finally locate him, safe and sound – and Christian – in the folds of the Church. The convent, as represented by their glib attorney, denied everything and accused the Jewish family of imagining the whole charade. The proceedings became quite messy.

The judge finally issued a ruling. “I sympathize with the plight of the parents but until they have proof, I cannot remove the child from the monastery. However, I will allow them five minutes to spend alone with the little boy, and if they can convince him that he is their son, I will allow the boy to leave with them.”

The parents rushed to the home of Rav Auerbach and explained the situation. They asked for advice and what to say to make the child remember them. Rav Auerbach told them that he wished to accompany them on their visit. At first, the Church refused this request, but thanks to his good relations with the courts, his appeal was granted post-haste.

On the day of the fateful meeting, the parents together with Rav Auerbach, the chief rabbi of Halberstadt, entered the convent and were ushered into a small room where the boy was waiting for them. He was a Christian boy now, through and through, and had very little interest in meeting with these Jews. He was only there because the court forced him to spend five minutes with these people. The parents looked at the rabbi and he told them to be silent; he would do all the talking.

Suddenly, Rav Auerbach removed his outer coat, revealing a snow white kittel. He placed a white yarmulke on his head and stood facing the boy. He opened up a machzor and in a voice full of yearning and devotion, he began to sing the words of Kol Nidrei. The haunting melody filled the small room and his voice ranged forth, as the timeless tune, sung hundreds of thousands – millions – of times over the course of millennia, seemed to hang in the air, suspending time. Rav Auerbach continued to sing and did not stop until he had completed the entire paragraph. Three minutes had elapsed – two minutes were left.

The boy was sitting upright in his chair, as he had been taught to do in the monastery. Rav Auerbach looked deeply into his eyes and asked, “Do you want to come with us and merit the benefits of both this world and the next? Or do you wish to stay here in this monastery?” The boy’s face was a mask, but after hearing these words, his outer façade cracked.

He jumped out of his chair and ran into his mother’s arms. “Take me away from here! I cannot remain here one more minute! I remember that tune from the synagogue and I wish to go back there and hear it again!” The boy sobbed and left the convent with his parents.

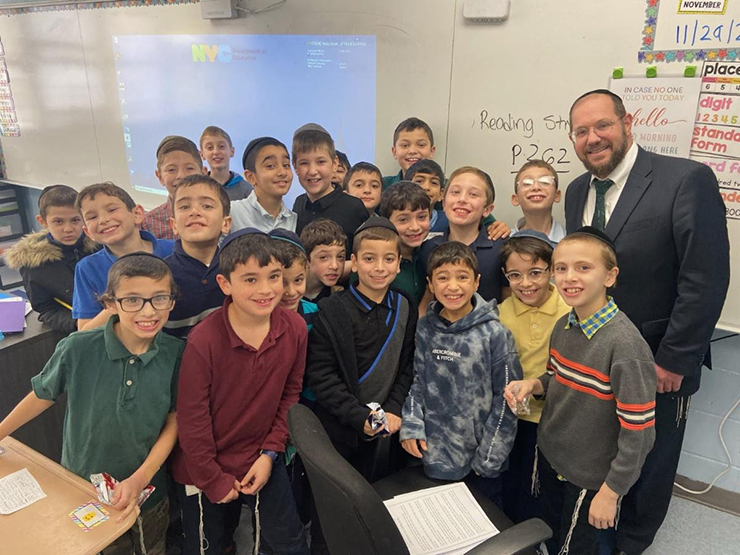

Rabbi Dovid Hoffman is the author of the popular “Torah Tavlin” book series, filled with stories, wit and hundreds of divrei Torah, including the brand new “Torah Tavlin Yamim Noraim” in stores everywhere. You’ll love this popular series. Also look for his book, “Heroes of Spirit,” containing one hundred fascinating stories on the Holocaust. They are fantastic gifts, available in all Judaica bookstores and online at http://israelbookshoppublications.com . To receive Rabbi Hoffman’s weekly “Torah Tavlin” sheet on the parsha, e-mail This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.