Throughout the entire parshah, we continuously read how Yosef, the favored son of Yaakov Avinu, suffered horrible humiliation, debasement, and extreme degradation. From the moment he was whisked away from his home and family to the abject slavery of an Egyptian master, finding himself thrown into jail for no fault of his own, it would have been logical for Yosef to become absorbed in his own pain, angry at the world. But Yosef did not become bitter. He remained sensitive to others and to his Divine mission in life. Not only did he perceive the anguish of Pharaoh’s servants, but he also reached out to help them. To Yosef, the fact that Hashem had arranged for him to notice someone in need indicated that it was his duty to help.

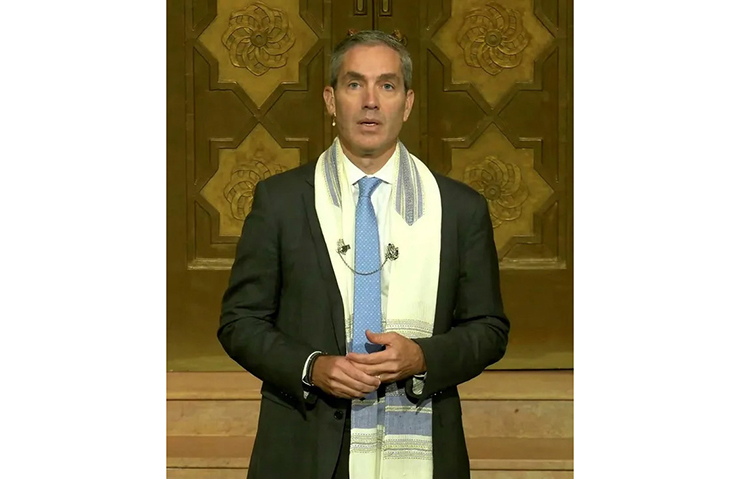

In his inimitable style, Rabbi Hanoch Teller vividly relates a story that he personally witnessed, which took place in his neighborhood in Jerusalem. It was Erev Yom Kippur, and as is the custom, men and boys flock to the nearby mikvah to prepare for the holy day. As Rabbi Teller tells it: In a mikvah, nothing is concealed! A young man by the name of Jamie, a newcomer to this mikvah, was a student at the nearby Ohr Somayach yeshivah. No one actually knew him, but with a ponytail and an earring, it was safe to assume that he was a recent baal t’shuvah, or at the very least, in the process of becoming one.

There was yet one other identifying mark that set Jamie apart, a dead give-away that he would have done anything to eradicate at that moment. His tattoos. All he could do was spread his hands over himself to cover his shame. His attempts at concealment, however, proved to be ironically effective at accentuating the very thing he wished to hide. Jamie gingerly made his way through the crowded room, arms folded over his biceps. It didn’t take a rocket scientist to realize what this beginner to Judaism was hiding. Many of the mikvah regulars gawked at him, insensitive to his predicament; Jamie met no one’s gaze.

And then it happened: Just a few feet from the water, Jamie lost his footing and slipped on the wet floor. In a reflex reaction, he lunged for the railing to avoid a collision with the mikvah’s steps. The muffled voices and cheery greetings came to an abrupt halt as all those present fell silent. Jamie’s biceps, decorated with gaudy tattoos, were exposed to public view, tattoos he had once proudly displayed not only as examples of the most artistic and skillful workmanship of the famed tattoo parlors of Hong Kong, Singapore, and other points east, but as a symbol of his toughness. Now, his shame was magnified.

For long seconds, a roaring silence enveloped the room. In a room that was loud and jovial just a mini-second ago, one could now hear the proverbial pin drop; imagine a boisterous Erev Yom Kippur mikvah reduced to a tomb-like absence of sound.

Jamie’s flailing hands reached out and his fingers thankfully found purchase on the metal banister that leads down into the water. He contemplated if breaking his fall by exposing his tattoos was a provident move. His mind wrestled with his instinct. Perhaps tumbling into the water and never emerging was the preferred route – anything not to suffer this humiliation.

The awful silence intensified, and the air became even heavier than before. Just then, an elderly man made his way towards the sacrificial goat as he held onto the railing. The slip-slap of his rubber bathing thongs thwacking against the damp marble floor created an eerie effect upon the throng waiting to resume breathing. Suddenly, Jamie felt the cold, wizened hand of the septuagenarian grip his shoulder. Slowly, hesitantly, he looked up at the stranger. Jamie saw something flickering far back in those moist deep eyes, which revealed the sensitivity of a Torah scholar, and all at once his fear left him.

In heavily Yiddish-accented English, the elderly man pronounced, “Look here, my boy, I also have a tattoo. In case I should ever forget what those monsters had planned for me.” He pointed to the row of numbers etched into his skin, an everlasting symbol of the Nazi method of shame and dehumanization for millions of Jews. “It seems we’ve both come a long way.”

Stretching out both hands, Jamie’s savior feebly attempted to help him straighten up. Others immediately rushed over to join in the effort, the spell of silence that had held them captive now broken. Jamie smiled gratefully and nodded to the old man, who patted him on his hands. And with that, the Erev Yom Kippur sounds of the bustling mikvah resumed as one after another called out to each other – and to Jamie – “G’mar Chasimah Tovah!”

(adapted from It’s a Small World by Rabbi Hanoch Teller)

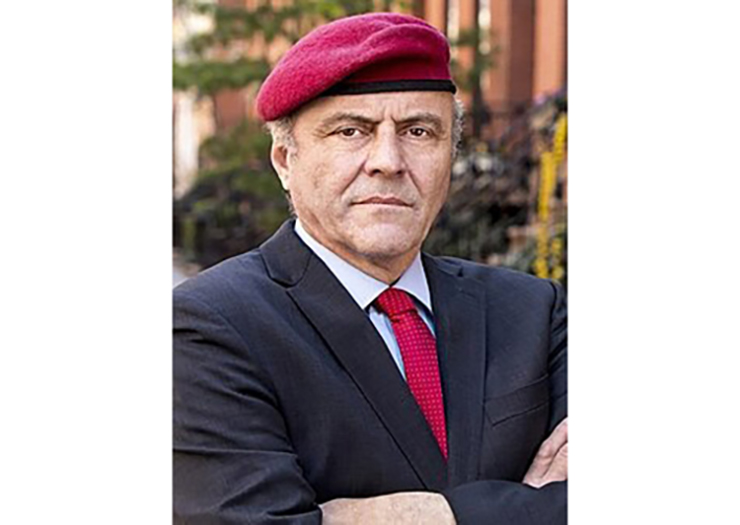

Rabbi Dovid Hoffman is the author of the popular “Torah Tavlin” book series, filled with stories, wit and hundreds of divrei Torah, including the brand new “Torah Tavlin Yamim Noraim” in stores everywhere. You’ll love this popular series. Also look for his book, “Heroes of Spirit,” containing one hundred fascinating stories on the Holocaust. They are fantastic gifts, available in all Judaica bookstores and online at http://israelbookshoppublications.com. To receive Rabbi Hoffman’s weekly “Torah Tavlin” sheet on the parsha, e-mail This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.