This is the third consecutive week I am writing a column from Israel.

Two weeks ago, I wrote about the war up until then for me, including guiding in Poland. Last week, I wrote about my son Matan who was injured (Baruch Hashem, he is doing much better).

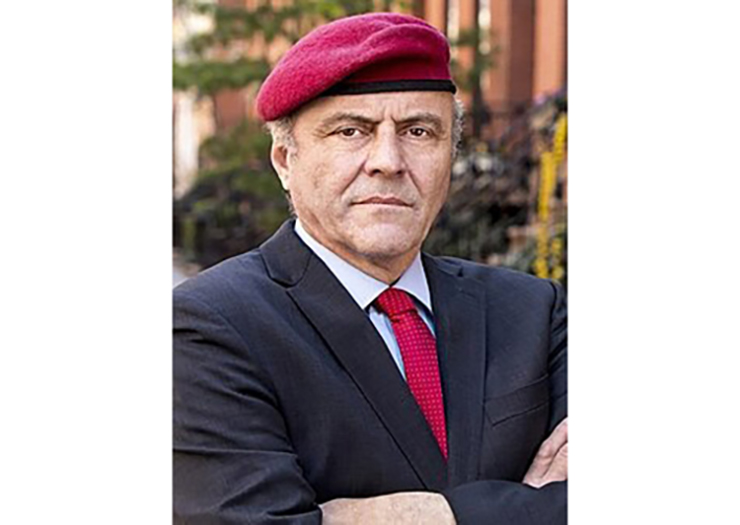

Sadly, this week is with the background of death, of funerals, and of shiv’ah. On Tuesday, ten fighters were killed in one day, including eight from Matan’s Golani unit. One of those was Moshe Bar-On, his commanding officer, pictured here congratulating Matan (who is wearing a flag) at the end of his final masa kumta (beret march) a month ago. This 23-year-old hero from Ra’anana commanded 100 soldiers and led them into battle, sacrificing his life in the defense of his country, in Gaza. His funeral was devastating, like the other nine recently, and the hundreds more that we have witnessed since October 7. Y’hi zichro baruch.

It shook us to the core, and sent us, like so many, to play the role of comforter. When an injured soldier forgets his need to rest and spends the time traversing the country comforting families and friends, aching to get back to the front lines, it is clearly an awful, terrible, heart-breaking week. Any other week, the sirens that sounded as we were saying Barchu for Maariv on Friday night, sending us running for the miklatim, would have dominated our thoughts – now that barely registers.

There is no question that Israel has been irrevocably changed since that fateful Simchas Torah, a mere 11 weeks ago. We will never return to “normal,” and, im yirtzeh Hashem, when the war ends, we will start living with a new reality. War is a sad reality of human interaction, a strange situation that makes different people out of us. It changes the normal to the abnormal and brings out both the hero and the animalistic nature of people.

From the moment the war broke out, and my son was called in on chag, and I was told that I was too old to return to my unit, I have felt that change. Not only is the country different, but the baton has been passed and the younger generation is now protecting us. After so many years of carefully protecting my son as he grew up, the tables have been turned.

So much has been written by so many people on a plethora of topics during this war. For me, the very act of writing is therapeutic, stops my feeling of guilt, delays any slide into panic, steels my resolve, and hardens my inner strength. Writing this column was not part of the plan for this war, yet here I am.

So thank you, QJL, for allowing me to express myself, when I – along with so many others – are so wildly unpredictable. Especially when the most mundane things have become like an ice pick through the heart: A simple knock at the front door has become one of the most terrifying sounds of my life.

Knock-knock. For those who are not aware, that is the way that people find out, chas v’shalom, that their loved one has been killed in the IDF fighting. It is a scene I experience regularly in my nightmares, which wake me up in a cold sweat: two or three soldiers at our door, at least one an officer, with grave yet practiced expressions of extreme concern on their faces, wearing a blue and orange ribbon signifying their unit, telling us the worst news possible.

Knock-knock. Thousands of people have had that sound change their lives forever over the past few weeks – tens of thousands since we took our first hesitant steps towards independent statehood.

Knock-knock. Baruch Hashem, I live in a neighbourhood where my kids have lots of friends who come over, and many tz’dakah collectors regularly frequent – but how can I possibly tell them what their knocking does to me? How can I tell them that, what was until 11 weeks ago the most normal sound in the world, immediately sends my heart into palpitations, adrenaline rushing, shortness of breath, and the worst thoughts to my mind. It’s hard to adequately describe how much that sound changes my mood instantly to pure fear and panic. Is this how all Israelis live?

Knock-knock. If I had to guess: For the rest of my life, that sound will bring with it a level of fear, maybe less as time goes by. I have, bli ayin ha’ra, four other sons, all of whom also intend to go to elite combat units when their time to draft comes. I can’t complain about that – that’s how we brought them up, with a love of both Torah and the State, and the knowledge that it is our responsibility, and the biggest mitzvah we will ever do, to protect our country from the evil that seeks to destroy us. Does it mean that I will always be listening for that knock with one ear?

And what do I do, every time I hear a knock? The only thing I can do – I steel myself, walk towards the door and open it. And, bli ayin ha’ra, breathe a sigh of relief, and continue my day. That is the response: the Jewish response, the Torah’s response.

As, l’havdil, that is exactly what happens at the start of this week’s parshah, VaYigash. Yehudah knows he is overstepping his boundary; he is facing someone who could kill him as easily as squashing a bug. I imagine his heart must have been pounding, sweating profusely, his adrenaline at a peak, as he stepped towards an unknown fate. I can very much empathise with that. Yet he did it. VaYigash eilav Yehudah – Yehudah takes that step forward and overcomes his fear, because that is the right and brave thing to do.

That’s what we do – as Israelis, as soldiers, as fighters. We respond to danger by shouting Kadimah! (Forward!) and we move forward, no matter the consequences, no matter the fear.

That’s what Moshe Bar-On did.

My blessing to myself is that I should not need to write a column next week.

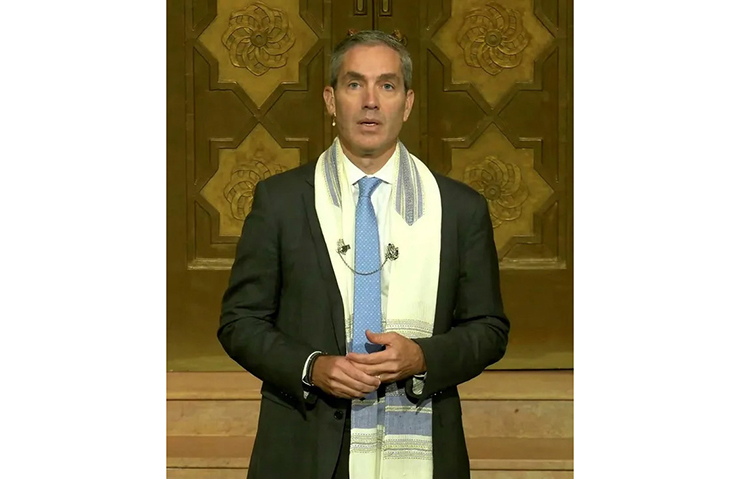

By Betsalel Steinhart