The toughest basketball player he had to guard was Shaquille O’Neil. The greatest player he ever saw play was Kobe Bryant. But Mike Sweetney’s greatest struggle was battling depression.

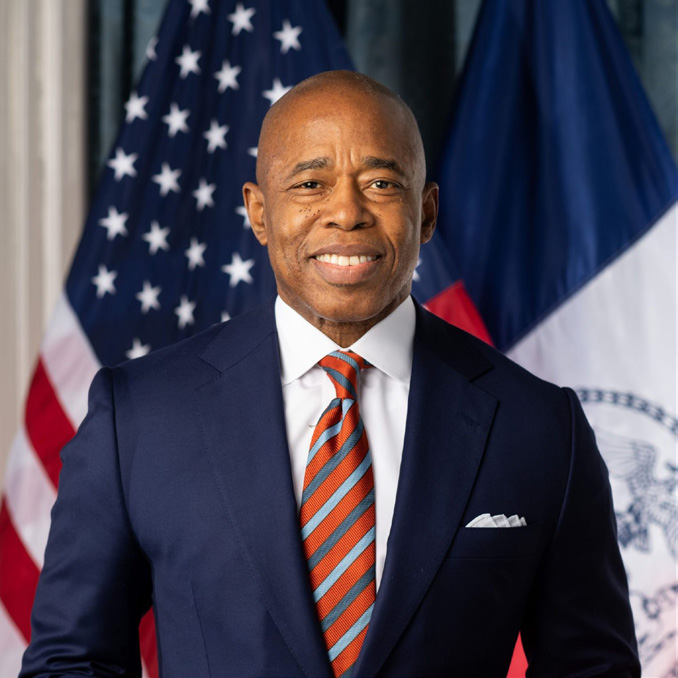

The former power forward for the New York Knicks spoke after a hot kiddush at the Young Israel of Forest Hills this past Shabbos. Rabbi Ashie Schreier gave a sermon of Torah and chizuk during services as part of the synagogue’s “Mental Health Shabbos.”

Sweetney was living his dream. His idol, Patrick Ewing, visited Sweetney in high school, encouraging him to play basketball and learn with legendary coach John Thompson at Georgetown University.

Mike’s father taught him love of the game starting at age nine. After Sweetney was a first-round draft pick for the Knicks, he found out rookies didn’t start, so he was going to spend a lot of time on the bench. Nonetheless, Sweetney was playing well and training camp was about to start. Then, his father died suddenly of a heart attack. “I felt like I didn’t belong there.”

Sweetney never had time to properly grieve nor were there adequate mental health services available to him. Sweetney kept his grief, doubts, and insecurities about his basketball abilities to himself. “I tried to hurt myself twice; let’s leave it at that.”

Sweetney was traded to the Chicago Bulls, where he played alongside Scotty Pippen. He was then offered to play for the Phoenix Suns but declined. He tried to hurt himself again. At times, he slept in parking lots and underneath bridges.

Throughout it all, his high school sweetheart, whom he married, stuck by him. He met with his first mental health therapist for about a year, but it wasn’t a good match. Then he found another therapist whom he talked with often, who made a difference.

Sweetney knew Tamir Goodman, “The Jewish Jordan,” for a long time. They played together at an All-Star tournament in high school. Goodman is Orthodox and was upfront with his struggles with depression and playing in the NBA.

Goodman asked Sweetney to coach at Camp Ramah, which Sweetney accepted. Sweetney had played basketball in Uruguay while Goodman had played in Israel.

Mike Sweetney is now the coach of the Ramaz High School basketball team and Assistant Couch of Yeshiva University’s Maccabees college basketball team, where they have a 35-game winning streak. In 2020, the Maccabees reached the Sweet 16 of the NCAA’s Division III national tournament before the pandemic shut down the rest of the event.

Sweetney said he now loves helping other people. He was forthright, open, and took questions from the more than 100 people listening attentively.

After coming out with his struggle with depression, the Knicks’ Stephon Marbury became a good friend and very supportive. Irwin Reiser, a member of the Young Israel of Forest Hills, said to Sweetney how he grew up and attended Lincoln High School with Stephen Marbury’s older brother, Eric, who also played basketball. Reiser knew the parents, Don and Mabel.

Reiser said of Sweetney, “My hat’s off to him. That’s a difficult thing to overcome, a medical issue like that of depression. He seemed to be energetic and quite happy about what he is doing.”

Rabbi Ashie Schreier of the Young Israel of Forest Hills discussed his sermon after Shabbos. “We are commanded to love others as we love ourselves. A prerequisite to loving others is to make sure we love ourselves.”

While we shouldn’t judge others, we are told to judge others favorably. “We should give ourselves the benefit of the doubt. Our mentality is to make sure we give ourselves a break.”

“There are many thoughts in the head of man,” which is from the morning prayer, Y’hi Chavod, before Ashrei. “Much of that can be doubt and anxiety,” said Rabbi Schreier. Quoting Rav Wolbe, the advice of Hashem is to get up, keep moving, push through, and try to make sure that one is forgiving towards one’s self. “We have to be able to forgive ourselves and continue moving forward. We can be our own worst critics.”

A Harvard study asked people on top of a mountain how steep a decline looked. Those alone on the mountaintop saw the decline much steeper than those not alone. “When you’re able to be there for people and with people, it’s a profound impact,” said the Rabbi.

“Many people go through so many things and have these types of struggles, and as a community, we need to be able to support.”

“The feeling of isolation is one of the most devastating parts of mental illness and that’s for the person struggling and for the family. So try to do our part to make sure people don’t feel alone, and understand that you’re not alone.”

The Hebrew word for desolation and destruction are spelled the same way as neshamah (soul) in Hebrew. The differences are the vowels underneath the Hebrew words. “If you change the patach vowel to a kamatz vowel, if you give it a little bit of support, all of a sudden it goes from desolation to the loftiest thing in the world, which is a neshamah. Support makes all the difference.”