At a time when some urban lawmakers are rallying to defund the police, their suburban counterparts voted last week to empower them. On Monday, August 2, the Nassau County Legislature voted to allow police to sue for damages against individuals who harass, menace, or injure members of this profession. “It is the judgment of this legislature that the recent widespread pattern of physical attacks and intimidation directed at the police has undermined the civil liberties of the community at large,” the bill’s sponsors noted.

Drafted by Joshua Lafazan, an Independent from Syosset, its co-sponsors included Democrats Delia DeRiggi-Whitton, Arnold W. Drucker, and Ellen Birnbaum. In a six-hour hearing ahead of the vote, civil liberties advocates and Black Lives Matter activists argued before lawmakers that the bill would discourage protest and silence critics of police abuses. Convinced of their views, Drucker withdrew his support and voted against the bill. Among the supporters were Councilman Ed Muscarella, a Republican who represents West Hempstead, and his fellow party member Howard Kopel who represents portions of the Five Towns. Birnbaum’s district covers Great Neck.

Westbury legislator Siela Bynoe argued that declaring a police officer as a protected class is not the same as a race, gender, disability, or religion. “They can hang up their uniform. I can’t hang up my Black skin. It’s a personal affront. It’s not right.”

Speaking for his members, Brian Sullivan, President of the Nassau County Corrections Officers Benevolent Association spoke in support of the bill. “I firmly support this legislation that will seek to protect the basic human rights of any first responder,” he told lawmakers. “I, for one, do not go to work every day thinking this is the day I’m going to get assaulted, bit, punched, stabbed, and, oh well, that’s just part of my job.”

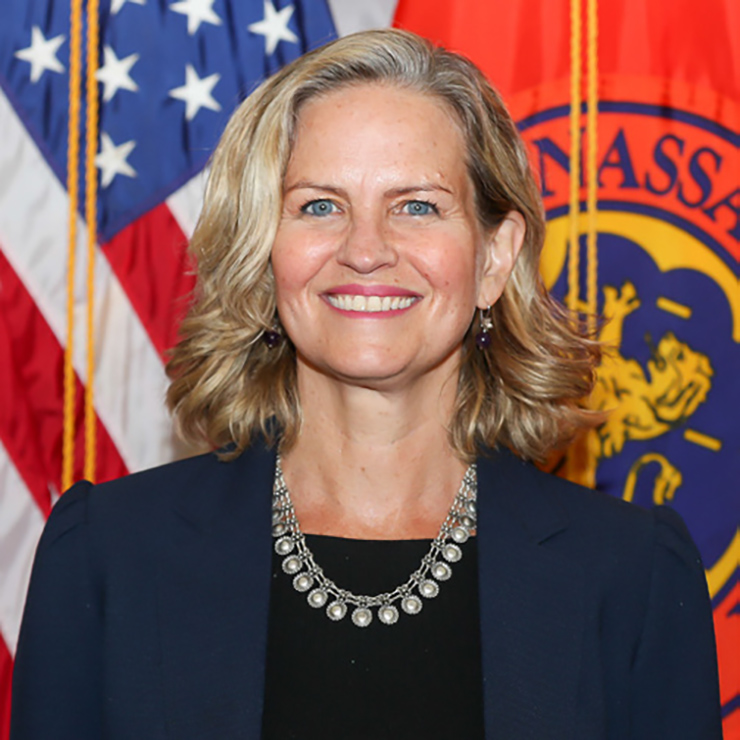

To become law, the bill must be signed by Nassau County Executive Laura Curran. While expressing support for police, she sent the bill to state Attorney General Letitia James for advice. “There were many speakers today who questioned this legislation,” she said. “Now that it has been passed by the legislature, I will be making an inquiry to the Attorney General’s Office to review and provide some advice.”

One can imagine the possibility of an aggrieved officer suing a demonstrator for using a slur against law enforcement and tossing insults during an arrest as examples where freedom of speech would be limited by the cop’s ability to sue for up to $50,000 in damages. Opponents of the bill noted that none of the Black Lives Matter rallies on Long Island had incidents of violence against the police.

Looking ahead, if the bill dies on Curran’s desk and fails an override by lawmakers, perhaps Lafazan’s goal was to generate a conversation by “trolling” the leftists on the meaning of “protected class” and “discrimination.”

The difficult work of first responders should not be aggravated by verbal harassment and abuse on social media. As protesters have their right to privacy, corrections and police officers should also be able to return to their homes after work with peace of mind.

As many of our readers who relocated from Queens to Nassau County are realizing, suburban politics may not receive as much attention in the press as the city and state, but the times are changing. Curran, a Democrat, won her seat in 2017, flipping it in favor of her party after decades of mostly Republican county leaders.

This year, she is up for reelection against Republican challenger Bruce Blakeman, a Hempstead town councilman. Unlike urban Democrats who often appeal to a progressive base, their suburban counterparts aim for a swing vote that is concerned about property taxes and public safety more than social justice concerns and redressing historical grievances.

By Sergey Kadinsky