The most diverse borough in the world twice hosted the World’s Fair - in 1939 and again in 1964. The first Fair was the largest in the history of such expositions, but it was overshadowed by World War II, in which the Czechoslovak and Polish pavilions were orphaned as their homelands were snuffed by Nazi Germany. The second Fair, at Flushing Meadows, had its own controversies, which related not as much to war as the rules governing a World’s Fair.

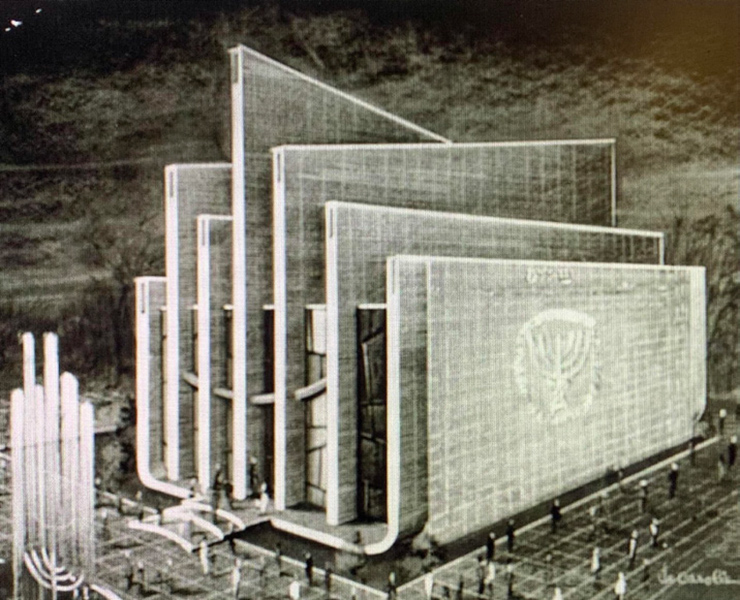

In the collection of the New York Public Library are the records of the 1964-1965 New York World’s Fair Corporation, which was given a lease on Flushing Meadows to host the event. Among the photos and illustrations is a sketch titled Proposed Israel Pavilion. It had no date, and the artist’s signature is difficult to read. Making up for the lack of words is its majestic design.

Inspired by a six-branched menorah, the building’s facade has seven panels of concrete connected by glass, surrounded by a moat. The tops of these panels appear jagged from above, seemingly like sheets of paper from the People of the Book. On the outermost panel would be a relief of the State emblem, the menorah that appears on the Arch of Titus in Rome. Finally, in front of this pavilion there would have been a menorah sculpture fountain.

It was an ambitious modernist design comparable to the chapels of JFK Airport and the palatial suburban Jewish centers associated with architect Percival Goodman. This proposed pavilion did not have to fit stylistically with its neighbors. The Bureau of International Expositions, the governing body of official World’s Fairs, refused to sanction this fair, citing World’s Fair designer Robert Moses’ leasing conditions as unreasonable and the fact that Seattle had an approved World’s Fair in 1962.

Moses invited private companies to step in and any government willing to defy the BIE. Britain, France, and Canada refused to participate, and the communist bloc also had no interest in sharing space in a fair where the majority of pavilions represented private corporations.

As it occurred during a period of decolonization, young countries such as Indonesia and Sudan were eager to introduce their cultures, economic potential, and tourism, to fairgoers. In Israel, there was debate in the governing cabinet on whether to participate. That was when this architectural rendering was drawn, but it was not the final design. Israel was a young and poor country, and it approved the modest pavilion by Brazilian-born oleh David Resnick over the massive concrete menorah. Resnick’s design echoed the Bauhaus style of Tel Aviv: white, curvy, and made of concrete.

In October 1962, Prime Minister David Ben-Gurion’s cabinet rejected participating, citing the high lease costs imposed by Moses on the pavilions. As Israel was a member of the BIE, it complied with its decision.

Pro-Israel organizations expressed dismay, fearing that in the battle for American public opinion, the Fair was an important venue in presenting the case for Israel. “It would be a great loss if Israel, a bastion of democracy in the Middle East, were unable to exhibit at the World’s Fair,” Rabbi David H. Hill wrote to Ben-Gurion, in his role as president of the National Council of Young Israel.

In contrast, Egypt and Jordan, at the time sworn enemies of Israel, had their pavilions. Jordan even had a mural of Palestinian mother and child, refugees displaced by “strangers from abroad” who were “buying up land and stirring up the people.”

Hill’s letter argued that if Israel couldn’t afford to participate, “We will find wholehearted response among individual Americans.” Rabbi Hill’s threat was formulated by a group of activists and philanthropists, the American-Israel World’s Fair Corporation, chaired by Harold Caplin.

A year after Ben-Gurion’s rejection of the fair, ground was broken on the American-Israel Pavilion. The ceremony was attended by Sen. Kenneth Keating, Moses, with an invocation delivered by Rabbi Harold H. Gordon, who served as the executive vice-president of the New York Board of Rabbis and a co-founder of the International Synagogue at JFK Airport. He spoke of the shared values of the United States and Israel.

In his remarks, Moses spoke of the recently discovered Dead Sea Scrolls, desalination, atomic energy, and the Technion Institute. Caplin then presented a stone from Shlomo HaMelech’s mines in southern Israel to Moses.

The design of this privately funded pavilion, by architect Ira Kessler, involved a circular structure with a spiral wall evoking a scroll. “This pavilion will be a sculptural expression of the Hebrew concept of ‘aliyah,’ the surging impulse of hope rising over despair,” Keating said. “The eternal dynamism of those laws on which our western culture is still based underlies the architecture of this pavilion.”

Upon the closing of the Fair, the pavilion was demolished and its site was covered with grass and trees. Israel officially returned to the World’s Fair scene with Expo 67 in Montreal, and most recently at Expo 2020 in Dubai. Its next appearance among participating countries will be at Expo 2025 in Osaka, Japan.

By Sergey Kadinsky