Strolling in the Beis David neighborhood in Yerushalayim, this writer and her husband passed a building with a plaque and stopped to read it. We discovered it was the Rav Kook House Museum. When we stepped inside, we were transported back in time to explore the life of the great tzadik, Rav Avraham Yitzchak HaKohen Kook.

Rav Kook was born in September 1865, on 19 Elul. He was niftar in 1935, on 3 Elul. Rav Kook – the first Ashkenazic Chief Rabbi of Israel – was one of the most influential rabbis and Jewish thinkers of the modern era.

Our private tour began in a large room that our lovely Israeli tour guide said was the room where Rav Kook met with anyone who wished to speak with him. The house was always open, except for one hour a week when he learned privately with his chavrusa.

Our tour guide pointed to a long table and chairs which – like his house – are about 150 years old. There is a shul and a beis midrash adjoining the house, and the shul is still used for Shabbos davening.

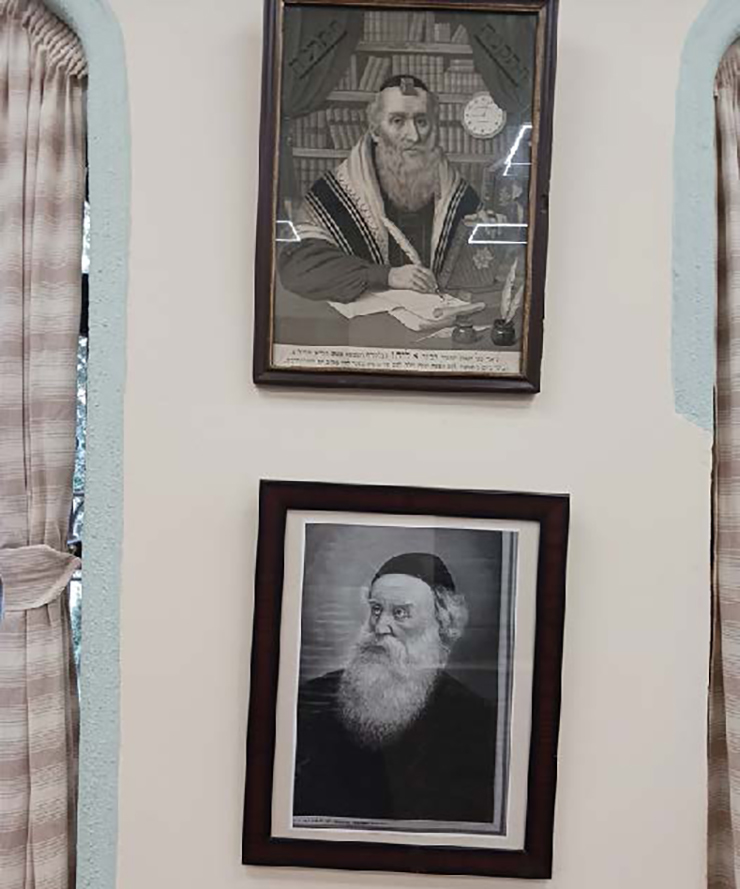

The photos of great rabbis on the wall in this room tell the story of Rav Kook’s philosophy. There is a picture of the Vilna Gaon and, near it, a picture of the Baal HaTanya. Rav Kook said, “They are together on the same wall as they are together in my heart.”

There are photos of various famous people with whom he met. Among them is a photo of Albert Einstein, the King of Iraq, and various noted writers and artists. He had an incredible gift for seeing the good inside each person and loving every Jew. He saw the pioneers’ secular agricultural work as part of a Divine process of redemption, even if they themselves were not observant.

There is also a photo of Eliezer Ben-Yehuda, founder of the modern Hebrew language, who was not at all religious. The tour guide shared an incredible story about their relationship. Ben-Yehuda would come to consult with Rav Kook about various Hebrew words.

Once, he entered during the usual private time when Rav Kook was learning with his chavrusa, Rav Yitzchak Arieli. Rav Kook patiently answered his questions about the etymology of some words in the Gemara. After he finished helping him, Rav Kook looked up and asked quietly, “Mr. Ben-Yehuda, when will you do t’shuvah?” Mr. Ben-Yehuda replied, “Ulai (perhaps).”

The next day, Ben-Yehuda was niftar. A question arose about where he could be buried. Since he said “perhaps” about doing t’shuvah, he was permitted to be buried on Har HaZeisim (the Mount of Olives).

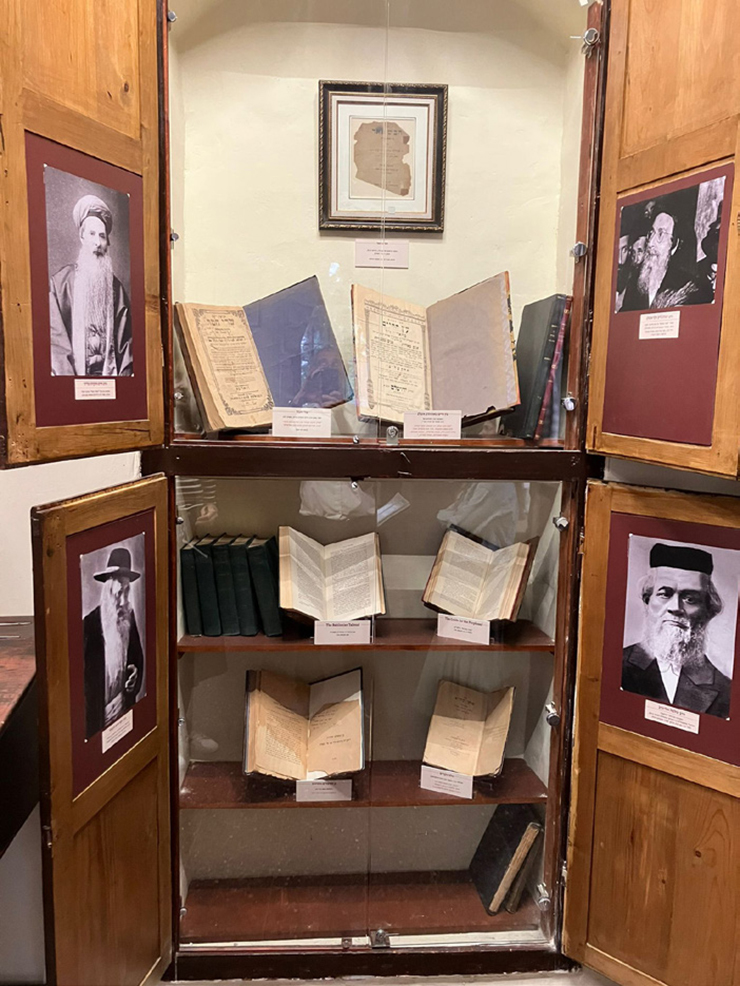

The tour guide showed us Rav Kook’s private study, including his original chair, desk, and s’farim. She also showed us a case with some of his personal effects. There was a pipe that, she said, he smoked Motza’ei Shabbos to calm himself as the neshamah y’seirah of Shabbos departed.

The shul displays photos of his famous talmidim, including Reb Aryeh Levin zt”l, Rav Yaakov Moshe Charlap, Rav David Cohen (the Nazir), and others.

He is considered the father of religious Zionism. He started a yeshivah adjacent to the house, which grew so large it is now located in Kiryat Moshe and is called Mercaz HaRav. Today, Yeshivat Mercaz HaRav is one of the largest Torah centers in Israel, with over 600 talmidim.

We asked about a carpet in a glass frame mounted on the wall. The tour guide told us that it was given to Rav Kook when he spoke at the opening of the Bezalel Academy of Arts and Design. Rav Kook told a story then about a little girl named Shoshana who was lying sick in bed with her eyes closed. One day, she opened her eyes, and the first thing she asked for was her little doll. Rav Kook explained the parable: Am Yisrael has been sick all these years in galus. The first thing to open is an art school – because am Yisrael needs all aspects of life.

His daughter once saw him writing on a paper on his shtender. After he filled the paper, he continued to write on the shtender. He told his daughter, “The paper finished, but the idea continued.”

It took his son, Rav Tzvi Yehuda Kook, 20 years to organize his father’s notebooks for publication. Some of Rav Kook’s famous works include: Orot (“Lights”) – his central visionary work on redemption, Torah, and Zionism; Orot HaT’shuvah – a spiritual and poetic exploration of repentance; and Orot HaKodesh – collections of his mystical and philosophical teachings.

In 1929, when Arabs rioted and massacred Jews, Rav Kook took survivors from the riots into his home. He also took in two sifrei Torah that were rescued. A donor paid for the scrolls to be repaired, and those Torah scrolls are used every Shabbos now in the shul.

At one point, Rav Kook traveled to the United States and visited the White House. There is a photo of him shaking hands with President Calvin Coolidge.

When he died 90 years ago, just two weeks short of his 70th birthday, one-quarter of the entire population of the land – and even Arabs – attended his l’vayah. During the l’vayah, stores closed out of respect.

Rav Kook’s son, Rav Tzvi Yehuda, carried on his teachings, especially in the Yeshivat Mercaz HaRav in Yerushalayim.

Rav Kook didn’t have an easy life. His first wife died when their first child was a year and a half old. That child later died of tuberculosis. He married again and had three other children: a son and two daughters; one of the daughters died in childhood as well. In addition, he had to deal with much controversy during his lifetime.

This writer asked our young Israeli tour guide what sparked her interest in Rav Kook. Her eyes lit up as she shared that she started learning his sefer Orot, and it opened a whole world for her.

On your next trip to Israel, which, im yirtzeh Hashem, will be very soon with the coming of Mashiach, I recommend that you stop off and tour the Rav Kook House Museum. It is truly inspiring to learn about Rav Kook’s life and legacy.

By Susie Garber