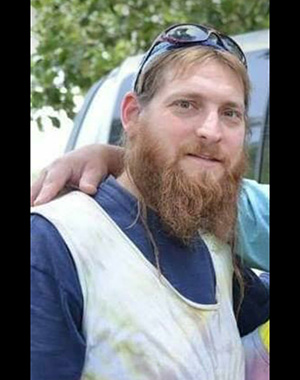

If there is a word that could encapsulate who Yitzchak Katzburg was, Sababa would be that word. He was ready for everything life threw at him, and at every turn, it was simply, “Sababa.”

Late last Friday afternoon, a tremor ran through Kew Gardens Hills as news started spreading that Yitzchak Katzburg was killed earlier in the week at his home in Tsefat. Yitzchak was only 38 years old but packed more into his short lifetime than most people do in 80 years.

Yitzchak was born and raised in Kew Gardens Hills. His parents made aliyah in the early 2000s and Yitzchak remained in Queens. Over the years, he occasionally spent time in Israel, but frequently returned to Queens, often for extended periods.

Yitzchak was an extremely creative person. He built LEGO cities as a kid, painted, blew glass, created fish tanks (some with menorahs inside), cooked, especially a good barbecue, and so much more. After he went to the army, Yitzchak used these abilities to create tie-dye tzitzis and learn safrus.

He used his creative mind to help his hometown of KGH as well. As a member of Hatzalah, Yitzchak (Q133 as he was known) would spend days driving around town learning all the streets and making notes of the best routes to take when on a call so that he could get to the scene seconds more quickly. He used his creativity to save lives!

Yitzchak’s love for sports was not exclusive to watching; he loved playing, as well. He loved softball and basketball, but his biggest love was tackle football. Yitzchak’s friends in Israel know him as the beast, starting defensive end and tight end for many years – on a bum knee!

At 16, Yitzchak decided that he wanted to join the Israeli Army but understood that his knee would be an issue. Undeterred, he started a strict workout regimen until he was confident that his knee was strong enough to enlist. He needed money, so he became a roadie for Jewish bands. He needed to learn Hebrew, so Yitzchak flew to Israel with Birthright and found a place to do Ulpan. Nothing got in his way.

His stint in the IDF started with Yitzchak doing Border Patrol and, eventually, he was placed with a group of soldiers doing secret missions in enemy territory.

Many of his missions were in small towns where his team needed to make an arrest. Of course, these were undercover missions, where if they were seen it could very easily mean death. He would recreate these moments so nonchalantly as we sat spellbound, focusing on each word. He would often joke, “I was so good with a gun in real life, but I couldn’t shoot a thing in the video game Call of Duty.”

For Yitzchak, the army was not just a thing to do, just another adventure; it was a purpose. When invited to speak to a chasidish class about the army, Yitzchak spoke about responsibility, discipline, and the mitzvah. Yitzchak felt his role, his place, at the time was to be fighting for Israel. Being in the Army was his mitzvah.

Yitzchak was also always looking to do the mitzvah of chesed. While living in Tsefas, Yitzchak would always cook for 15, as his home was open to anyone needing a meal, and he never knew how much he really needed to make. His dirah had an extremely big mirpeset and there was a stack of Israeli mattresses lining the wall, ready to be used for guests. If sleeping on the porch was not enough, Yitzchak would say “sababa” and give up his own bed.

His mirpeset also became a central location for his biggest chesed of all: his tie-dye tzitzis. Yitzchak wrote, “How did tie-dye tzitzis start? About ten years ago, at a Music Festival in Israel, a group of friends wanted to do something for the festival and they tie-dye colored tzitzis. Another few friends took them and gave them out at the festival. The first batch was 50 tzitzis garments. And it caught on right away. So, more tie-dye tzitzis were made and were given out in Zion Square in Jerusalem on Thursday night at the busiest time of the week with the youth of the Israeli nation packing town, enjoying the Jerusalem nightlife. About 150-200 tie-dye tzitzis garments were given out every Thursday night with the condition that the one receiving the tie-dye tzitzis would wear it over his clothes for the rest of the night. Suddenly you saw central Jerusalem filled with every type of Jew walking around wearing tie-dye tzitzis.”

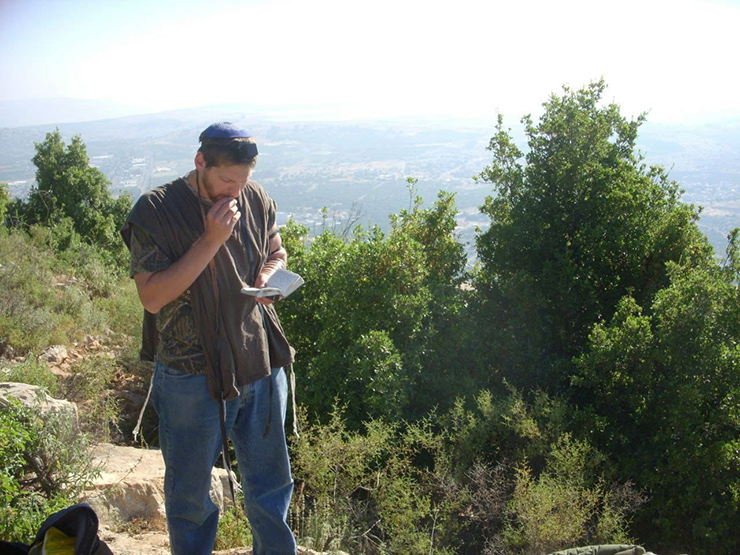

T’filah was very important to Yitzchak – especially hisbod’dus, where he would find a very private area, somewhere nobody would hear him, and talk to Hashem. Yitzchak would explain: “When you talk to Hashem like you talk to a friend, in your own language, holding nothing back, Hashem will talk back to you right away.” He would go with his rebbe in the middle of the night to Shmuel HaNavi’s kever and they would do hisbod’dus, or as he would say, “just talk to Hashem.”

Yitzchak loved Torah; however, learning was very difficult for him. Not one to give up, he started by using an English Tanach and went through it, book by book. Eventually, Yitzchak and I started learning the Gemara in Makos, and eventually, we were able to finish four masechtos together. For one masechta, Yitzchak would take a bus from his home in Yerushalayim to where I was learning in Ramat Shlomo, a 25-minute ride each way, just to learn for 30 minutes. That was his desire and love for Torah.

Whether it was a game of softball, a l’chayim after shul with vodka, cake, and sunflower seeds, playing Sheshbesh, making tzitzis, playing video games (even minesweeper), taking a cross-country road trip (using only the side roads and paper maps, of course), camping out on a random mountain, or just hanging out, you felt alive with Yitzchak around. He was not afraid of life, and he faced every trial and tribulation with tremendous emunah, faith that Hashem would take care of him. His emunah was tangible. Countless people told me that they never saw Yitzchak sad or down; rather, he was always happy and b’simchah.

Once, Yitzchak lost a lot of money, but he said to me, “Shloimy, it is only a few weeks until Rosh HaShanah, and before Rosh HaShanah, Hashem needs to balance his books from the previous year. I know for sure that I needed to lose that money, and this is a kaparah for me before the new year.” He wasn’t sad and depressed but happy and content.

Yitzchak was taken from us right before Chodesh Elul. Perhaps, this is Hashem balancing his books and giving klal Yisrael a kaparah before the new year. Yitzchak would not be sad or depressed; he would be happy and content, because when Hashem told Yitzchak that he needed his neshamah back, I’m sure Yitzchak’s answer was, “Sababa!”

Y’hi zichro baruch.

By Shlomo Teitz