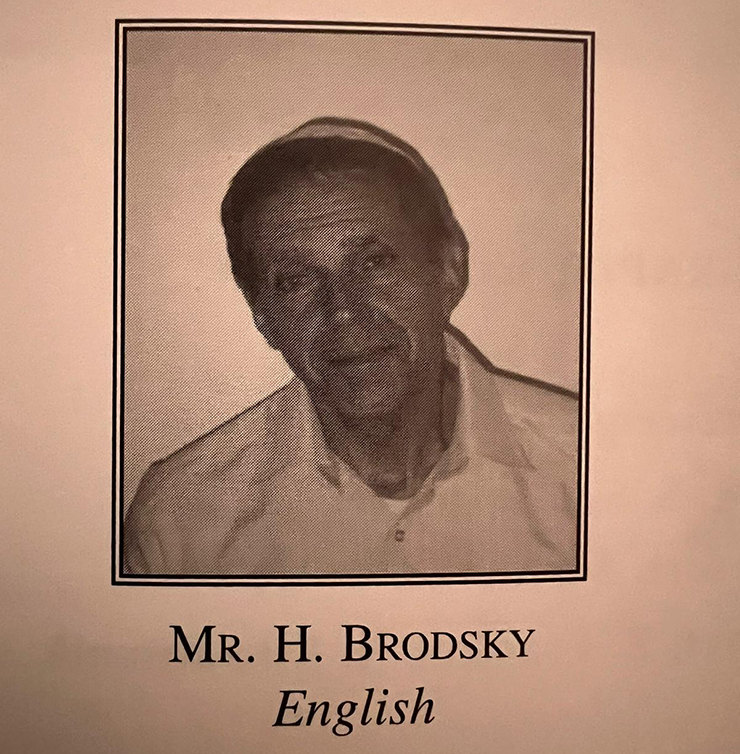

Being an English Language Arts (ELA) teacher in an Orthodox Jewish all-boys school isn’t exactly the easiest teaching gig in the world. I should know – I did it for two years. The difficulty stems from the idea that the main skill you must impart on your students is critical thinking, a skill the boys tend to hone throughout their Judaic studies curriculum starting in the fifth grade. However, some people were born for such a position.

Harvey Brodsky was such a man.

With the rise of a teacher’s strike in New York City public schools, which began in May 1968 and continued through the start of the next school year, out-of-work teachers looked for alternative opportunities. A friend told Mr. Brodsky about an opening at a Kew Gardens yeshivah. That same year, Mr. Brodsky started teaching at Yeshiva Tiferes Moshe. The rest is history.

Mr. Brodsky continued teaching in a part-time role once the strike was over, and after his retirement from the public school system, he came back to teach four classes – two seventh-grade and two eighth-grade classes – until his retirement in 2014.

So, what made him so great? How was he able to take a difficult subject for adolescent boys and make it meaningful and worthwhile enough that decades of students sing his praises? Perhaps that answer is best given by his last principal in Tiferes Moshe, Rabbi Herbert Russ, who served from 2000-2014: “He was a phenomenal teacher who taught kids how to write. He used every kind of educational method he could think of to help the student be confident in writing.” You see, critical thinking was only part of the equation. Thinking was the easy part. Imparting those thoughts cohesively through writing – that is where Mr. Brodsky shined.

Barry Simanowitz (class of ’77) explained, “He never allowed us to be dumbed down. He demanded the best and taught a bunch of yeshivah boys how to get by through communication and writing. I learned more from him in seventh and eighth grade than I did in high school and college. And as a father, I was more than pleased to know that my sons were going to have the same level of education.”

Actually, there were a few instances where Mr. Brodsky taught a third generation, but he certainly had many examples of teaching multiple members of the same family. Yona Zweig (class of ’04) told me that “Mr. Brodsky was a skilled and passionate educator who taught generations of students about the beauties of English, both the language and its literature, and who emphasized the importance of critical thinking in all things, a skill that applies across all areas of life.” Yona’s uncle, Uri Kaufman (class of ’77), echoed these sentiments. “He was a great teacher who genuinely cared about us. He taught us lessons about literature and about life.”

We could probably fill several books with the praises Mr. Brodsky’s former students have for him, each one thanking him for the gifts he had bestowed upon them. This very newspaper has at least four contributors who credit Mr. Brodsky with teaching them how to write: Shabsie Saphirstein, Rabbi Yaakov Abramovitz, Managing Editor Naftali Szrolovits, and me. Each of us knows where our journey to writing began, and each of us is probably still terrified that he will have us add a word to our individualized spelling list every time we submit a piece.

Mr. Brodsky never had children, but through his 46 years of teaching, he has left his indelible mark on the world. He was one of the most remarkable teachers this world has seen, and he will be missed sorely.

Izzo Zwiren

Class of 2000

Izzo Zwiren works in healthcare administration, constantly concerning himself with the state of healthcare politics. The topic of healthcare has led Izzo to become passionate about a variety of political issues affecting our country today. Aside from politics, Izzo is a fan of trivia, stand-up comedy, and the New York Giants. Izzo lives on Long Island with his wife and two adorable, hilarious daughters.