When flying, some people prefer aisle seats, so they don’t have to bother anyone else when they want to get up. Other people prefer the window seat so they can enjoy the incredible views outside. But I don’t know anyone who prefers a middle seat. It’s the worst of all worlds. From the middle seat you can’t really see out the window and you don’t have direct access to the aisle. In addition, it seems to be an unwritten rule that the person in the middle doesn’t have dibs over the armrests. He must defer to his seatmates on either side.

In my younger years, I was very much a window seater. I was, and am, fascinated by the wonder of flying and love looking out the window. As I’ve gotten older, I’ve begun to prefer aisle seats so I can stretch my legs at will. On my recent trip to Eretz Yisrael, however, I apparently booked my seat too late and was designated a middle seat. Although it definitely wasn’t what I would’ve chosen, it was worth the discomfort to get to Eretz Yisrael.

When I boarded the plane and arrived at my seat, there was an elderly man already seated in the aisle seat and an elderly woman in the window seat. The man got up to allow me to go to my seat. Two minutes after I sat down, the man on my left turned to the woman on my right and asked her something, and she replied. A minute later she asked him a question, and he replied. I realized I was seated between a married couple. He wanted the aisle while she wanted the window, and I was stuck in between. They were very pleasant, but it was a bit of an awkward ten hours.

A few days later I saw the same couple on the side of the road in Geulah. They hadn’t seen me yet, so I walked in between them and announced, “This feels familiar.” They looked up with confusion. Then they saw me and laughed.

It brought back memories of the middle seat in the front row of a car. Today, that seat doesn’t exist. But in my youth, I remember many occasions sitting in the middle seat between my parents. I can’t even imagine driving anywhere today with one of my children sitting in the front between my wife and me. Aside from the discomfort, how would my wife and I discuss anything if a child was sitting between us, instead of trying to eavesdrop from the back?

I am grateful to my younger two siblings who rescued me from being a middle child. Middle children often feel that they get lost in the shuffle and have various gripes that include feeling somewhat forgotten.

In my early days of rabbanus, a veteran rabbi explained to me that in most congregations, 10 percent of the congregation will love the rabbi and back him almost regardless of what he says or does. Another 10 percent of the congregation will disdain the rabbi and challenge him almost regardless of what he says or does. The middle 80 percent fluctuate.

It’s to them that the rabbi should focus his efforts. The wise rabbi doesn’t waste too much time trying to convince the naysayers; their minds are already made up. Instead, he seeks to maintain a warm and positive relationship with the wavering mass in the middle.

In classrooms there is a constant tension that all teachers must contend with: whom to cater their primary efforts towards. Do they focus more on the quicker students of the class or on the students who need added explanation to grasp what is being taught. No matter which the teacher chooses, he/she should always be mindful of the students in the middle who often slide through the system.

Middles get a bad rap. But there is great significance and value of the middle.

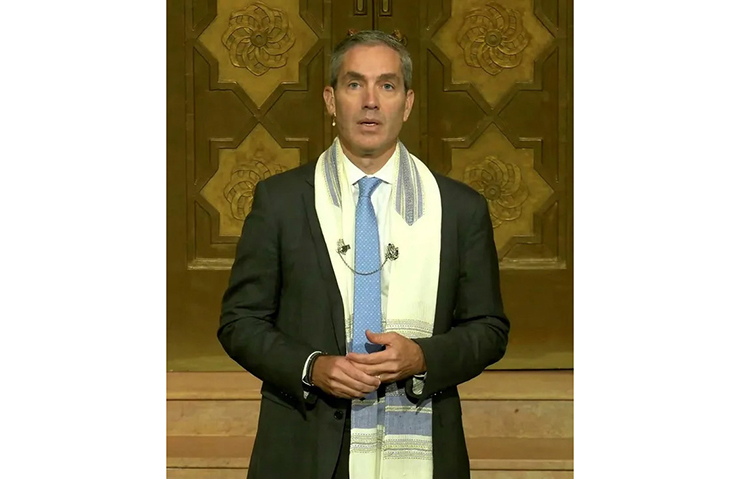

The Gemara (Megillah 21b) notes that the Menorah in the Beis HaMikdash had three branches on either side of the middle branch. The flames atop each of the branches faced the middle one, while the middle one faced the Holy of Holies, where the Shechinah was. Rabbi Yochanan noted that the middle candle atop the Menorah demonstrated that the middle is special.

Beginnings are challenging but they are also exciting. We gear up for new challenges and prepare for them. Endings are also special, fostering feelings of accomplishment and/or closure.

We celebrate book ends. We have Siddur and Chumash parties for our children when they begin davening/learning. We also have graduations to celebrate and mark the completion of their studies. In between, there is a long stretch of unremarkable learning and studying. But it is there, in the elongated, uncelebrated middle that the real learning and growth takes place.

The Mishnah (Avos 3:7) states that if a person is walking on the way and he interrupts his studies and declares, “How beautiful is this tree” or “How beautiful is this plowed field,” the Torah considers him as if he is liable for his soul.

What is so pretty about a plowed field? In addition, why is a person liable for his soul for admiring beautiful landscapes?

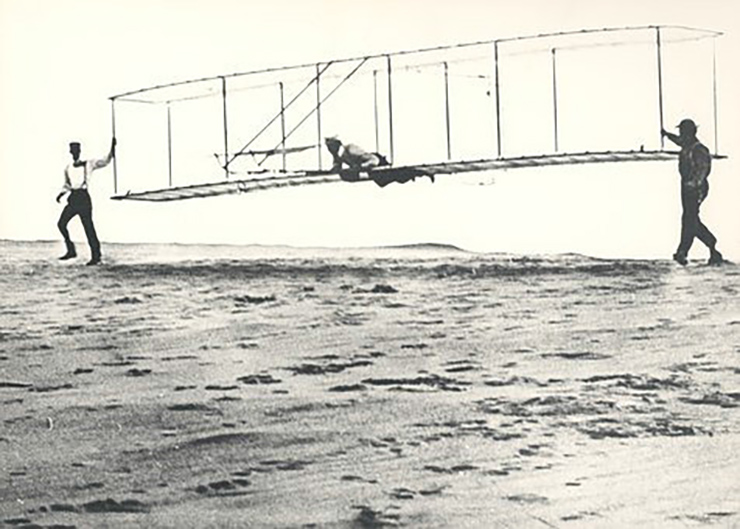

Rabbi Label Lam suggests that the beauty of a plowed field lies in its potential. Only a farmer who appreciates how much produce and profit can be generated from a yet uncultivated field would see it as beautiful. A plowed field represents potential waiting to be actualized, the coveted initiation of a potentially profitable process. In contrast, a beautiful tree represents actualization and accomplishment. A blooming tree stands regally, bearing its luscious fruits, waiting to be picked and enjoyed.

We all travel the paths and roads of life. Rabbi Lam suggests that the subject of that mishnah is trying to accomplish and grow but feels that his growth is stymied and stagnated. He admires young children, analogous to plowed fields bursting with potential. He recalls when he himself set out on the path of growth, wide-eyed and confident, before he became burned out. He also admires those who have accomplished and brought their dreams to fruition, analogous to beautiful fruit-producing trees. He sighs, feeling that his own dreams will never be actualized.

The mishnah warns that such a defeatist attitude destroys the soul. It depletes confidence and squashes dreams.

We are always in the middle of the paths of life. The middle may not feel exciting. But that is where one’s main efforts must be invested. As long as one can stay the course and maintain a sense of mission and direction, that is a success.

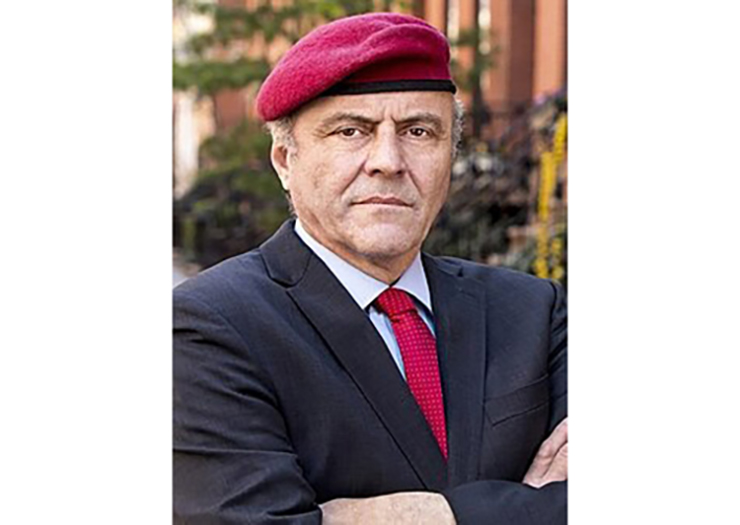

Rabbi Dani Staum, LMSW, a rebbe at Heichal HaTorah in Teaneck, New Jersey, is a parenting consultant and maintains a private practice for adolescents and adults. He is also a member of the administration of Camp Dora Golding for over two decades. Rabbi Staum was a community rabbi for ten years, and has been involved in education as a principal, guidance counselor, and teacher in various yeshivos. Rabbi Staum is a noted author and sought-after lecturer, with hundreds of lectures posted on torahanytime.com. He has published articles and books about education, parenting, and Torah living in contemporary society. Rabbi Staum can be reached at This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it. . His website containing archives of his writings is www.stamTorah.info.