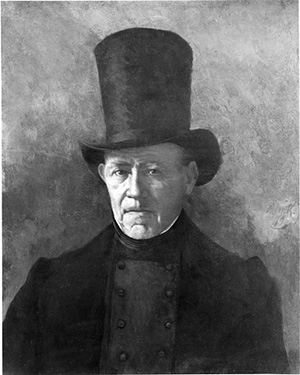

In the decade since I’ve begun teaching history at Touro College, which has since become a university with a new logo and headquarters, I’ve had plenty of time to think about its mission and name. Unlike many private universities, its namesake Judah Touro died more than a century before its founding, and none of his personal wealth had any impact on this university. Like any institution with a name, it tries to maintain some sort of a connection to that individual and highlight his contributions to this country.

In my classes, I’ve spoken about the duality of Touro’s activism and philanthropy towards Jewish and patriotic causes. Unmarried and childless, upon his death his fortune was distributed across a wide array of Jewish and secular causes, dubbed by reporters as the “will of the century.”

“When Jews are declared incapable of any sentiment above racial clannishness – that the Jew Touro donated ten thousand dollars towards the erection of the Bunker Hill Monument, intended to commemorate the second battle fought for American freedom,” wrote Henry Samuel Morais, in his 1880 book Eminent Israelites of the Nineteenth Century. “The private character of Mr. Touro was untainted. Simplicity, unostentation, and courtesy, qualities always reflected in the deeds of a true philanthropist.”

At a time when there was widespread anti-Semitism in American society, Morais served as the chazan of Mikveh Israel, the oldest Orthodox congregation in Philadelphia. Like his father Sabato, he was a defender of halachah against the rising tide of Reformism. Nearly a century earlier, this shul was in danger of defaulting on its debts in 1788. It was bailed out by that city’s leading patriot Benjamin Franklin, along with scientist David Rittenhouse, and future Pennsylvania governor Thomas McKean. Morais later served at the Touro Synagogue in Newport, Rhode Island, whose connection to the nation’s founders involved a letter written in 1790 by President George Washington that emphasized religious freedom.

“The Government of the United States...gives to bigotry no sanction, to persecution no assistance... May the children of the Stock of Abraham, who dwell in this land, continue to merit and enjoy the good will of the other inhabitants; while everyone shall sit in safety under his own vine and fig tree, and there shall be none to make him afraid.”

Touro’s father Isaac served as its chazan prior to the American Revolution, and it was among the beneficiaries of that massive will. Hence, Touro Synagogue became the English name for K’hal Kadosh Jeshuat Israel.

When Rabbi Dr. Bernard Lander zt”l established a new college in 1970, he was inspired by Judah Touro’s dual mission of strengthening the Jewish community while contributing to society. It is a university run under Orthodox auspices and open to people from all walks of life.

Like Touro, there is another Jewish patriot who has a university named for him. Louis Dembitz Brandeis was a consequential figure in Jewish and American history. A son of German Jews who valued culture, he grew up reading the works of Goethe and Schiller, and listening to the music of Beethoven and Mozart.

The Harvard graduate left an impact on American jurisprudence in regard to privacy law, freedom of speech, combating corruption, business monopolies, and the rights of employees in the workplace. He was the first Jew to sit on the Supreme Court, serving from 1916 to 1939. Brandeis was a latecomer to the cause of Zionism, having been raised with no formal Jewish education. His participation in the Zionist Organization of America demonstrated that one could be a patriotic citizen and at the same time a supporter of Jewish sovereignty. At the time, many American Jews were ambivalent or hostile towards a movement whose goals were regarded as unrealistic and the idea of supporting the independence of another country as “dual loyalty.”

Brandeis did not see any conflict between his duties as an Associate Justice and as president of the ZOA during World War I, when his friendship with President Woodrow Wilson ensured American support for the Balfour Declaration.

In 1948, the same year that Israel regained its independence, Brandeis University was founded in Waltham, Massachusetts. As was the case with Touro, the namesake died before its creation and was chosen for the honor because of his contributions to the Jewish people and American history.

Last week, Brandeis University was a subject of criticism for its full-page ad in The New York Times titled, “Brandeis was founded by Jews. But, it’s anything but Orthodox.” Unlike Yeshiva University and Touro University, which are run under Orthodox auspices while legally “nonsectarian,” Brandeis never had a religious identity. Its connection to Judaism was always cultural.

“It’s a natural mistake to make,” the ad added. “After all, Brandeis was founded by American Jews in 1948, including Orthodox, Conservative, and Reform Jews. But when we say that Brandeis is anything but Orthodox, we’re referring to its character.”

Online, prominent Orthodox voices on social media considered the ad “distasteful.”

“This kind of pun might be cute on a podcast or a JCC or even a Federation meeting. Not a cute pun as an advertisement in The New York Times,” tweeted NCSY leader Rabbi David Bashevkin. “I think a part of why I find this upsetting is that actual acceptances for Orthodox Jews at many of these colleges has cratered.”

He then shared a message from an Orthodox student who noted that Brandeis is respectful of its observant students regarding kashrus, minyanim, learning opportunities, and Jewish holidays.

Perhaps the school’s decision to point out that it is not Orthodox is a compliment to the visibility of Orthodox Jews in American society. It is the result of communities that value families, education, and the understanding of halachah. It is the latter element that enables Orthodox individuals to work in nearly every type of workplace without compromising our values.

At the same time, the ad cannot be dismissed entirely as an unintended compliment or an attempt at humor when there is a resurgence of anti-Semitic incidents across this country, particularly within higher education. The intolerance towards pro-Israel students was on full display at the CUNY Law School earlier this year, where students and faculty cheered on a graduating speaker’s tirade against Israel. Our values are under attack, as well, when Orthodox students’ faith is attacked for its views on gender identity and orientation.

As we celebrate the 247th year of the United States this coming week, we should reflect on our community’s contributions to the development of this country. For many individuals who have done their part, it involved changing their names, marrying out of the faith, and disparaging our traditions as outdated and out of line with society. Orthodox Jews in America offer a different message, one that Washington alluded to in his letter to the Newport congregation.

He spoke of individuals sitting in safety “under his own vine,” responsible to this country “as good citizens, in giving it on all occasions their effectual support.” The namesakes of Touro University and Brandeis University were loyal to their community and provided the highest examples of patriotism as citizens and public servants. Their example continues to inspire these respective institutions, and many other honors that carry their names.

By Sergey Kadinsky