Lone gunmen aren’t necessarily motivated by extreme rhetoric, but the shooting in Pennsylvania should put an end to the “anyone I don’t like is Hitler” discourse.

(July 15, 2024 / JNS) At what point does angry political discourse cross the line between legitimate impassioned advocacy and direct incitement to violence? It’s a question that’s been all too common in both the United States and Israel for the past generation.

It’s one that would be difficult to answer for even the most objective observers. But given that few of us are truly objective about the issues and disputes that generate the greatest amount of heat, most tend to respond along self-interested lines, treating our own positions as inherently legitimate and those of the people with whom we disagree as clearly beyond the pale.

That is why acts of political violence—such as the attempted assassination of former President Donald Trump this past weekend—can just as easily exacerbate the tensions within societies rather than help heal them. In seeking to understand how Americans can transcend their political divisions and recover some sense of national unity, we need to remember that two things can be true at the same time.

One is that the responsibility for acts of political violence belongs to the perpetrators alone and not to those who may share some of their political positions. That’s especially true when one realizes that many if not most such crimes tend to be committed by lone extremists whose motivations are often complicated by their own struggles with mental illness.

Bromides aren’t enough

Yet there are also times when the tone and content of political discourse can rise to a level of white-hot intensity that can create an atmosphere in which violence is easier to imagine, even if not necessarily inevitable. This is probably more the case in the third decade of the 21st century than ever before, when extreme sentiments can be magnified by mainstream corporate press groupthink and amplified by social-media platforms that tend to reinforce their users’ sense of self-righteous indignation and intolerance of anyone who disagrees with them.

And when the entire focus of the arguments of one end of the political spectrum is based on treating opponents as illegitimate and their leader as the second coming of Adolf Hitler—as the Democrats have treated Trump–it isn’t good enough to respond to an act of violence with bromides about lowering the temperature.

So, if you’ve been nodding along with those calling Trump Hitler and the half of the country that’s planning to vote for him as fascists or “semi-fascists” who want to end democracy, then maybe your reaction to the attempted assassination ought to be one of sober self-assessment rather than an attempt to ignore the context of contemporary political discourse with “both sides are wrong” arguments.

Those who are currently calling for civility, after having spent the last few years declaring that Trump didn’t warrant that sort of respect, spewing contempt for anyone who supported him and warning that the world as we know it would end if he returned to the White House next January, aren’t just a little late to the party. Members of the chattering classes who’ve done the most to set the national discussion on fire need to be honest about what they’ve been doing and the potential implications of their speech.

They especially need to look in the mirror, since most of those now playing the “both sides” game have never hesitated to assign blame to their opponents for acts of political violence.

Different standards

For the Israeli left, the accepted narrative about the most traumatic moment in their country’s political history is that the heated rhetoric of the right, and specifically current Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu, killed Yitzhak Rabin in November 1995. In the same way, most liberals, especially liberal American Jews, regarded the tragedy of the Oct. 2018 Tree of Life—Or L’Simcha Congregation mass shooting in Pittsburgh as Trump’s fault.

Both claims were false. There’s no doubt that the debate about the Oslo Accords led to irresponsible rhetoric by some of Rabin’s opponents, though not Netanyahu. It’s also true that Trump’s hyperbolic public comments and social-media posts helped coarsen political discourse. But the desire to blame Netanyahu and Trump was rooted primarily in partisanship. Their political opponents sought to link them to actions they had nothing to do with in order to discredit them.

The shooter’s motivation and so much else about the attack on Trump remains yet to be determined. The failures of the Secret Service to safeguard him against the sort of threat that most Americans assumed would be accounted for is particularly troubling. Yet there is always a double standard when it comes to judging such sad chapters in history. The mainstream media, which is dominated by the political left in both Israel and the United States, never hesitates to assign guilt for political violence on the right.

One of the most egregious examples took place in 2011, when Rep. Gabby Giffords (D-Ariz.) was targeted by a lone gunman in Tucson. Six people were killed and the congresswoman suffered permanent injuries that forced her to give up her career. While the shooter was a deranged individual with no discernable political ideology, the editorial page of The New York Times linked the crime to former GOP vice presidential candidate Sarah Palin, whose political action committee had circulated a list of districts represented by Democrats, including that of Giffords, which they wished to defeat for re-election with cross-hairs.

Were the media now to use the same standards employed at that time, President Joe Biden—who once claimed that Republicans like Mitt Romney would put African-Americans back “in chains”—would be blamed for the attempted assassination of his opponent, since only a week before the shooting, he told Democratic donors that “it’s time to put Trump in a bullseye.”

Incidents like the 2017 shooting of congressional Republicans and the attempt on the life of U.S. Supreme Court Justice Brett Kavanaugh in 2022 were both politically motivated. Those crimes could also have been blamed on the left’s demonization of the victims far more easily than Trump was for the Pittsburgh shooting.

Democrats aren’t the only ones who need to be careful about inflaming their supporters. Trump’s comments about the 2020 election results certainly set the stage for the Jan. 6 Capitol riot, even if he also cautioned those who had come to the “Stop the Steal” rally in Washington, D.C. to demonstrate “peacefully and patriotically.”

When some of them didn’t follow that advice and, instead, fought with police and broke into the Capitol building, Trump didn’t speak as quickly or as forcefully about that as he should have. He has also sometimes downplayed it since then, even as Democrats inflated a disgraceful riot by a few hundred people into an “insurrection” in which much of the Republican Party was falsely implicated.

Yet the Democrats who cried foul about Jan. 6 had not been as scrupulous about condemning violence the previous summer. That’s when the “mostly peaceful” Black Lives Matter riots spread across the country, resulting in attacks on government buildings and far more violence, including deaths, than that which occurred on Jan. 6. To the contrary, many of them excused or rationalized the rioters.

The same can be said about the way much of the liberal media has normalized the violence against Jews and the surge of antisemitism that has taken place in the last nine months since the Oct. 7 Hamas attacks on Israel.

Pulling back from the brink

There are signs that both parties understand,in the wake of the assassination attempt, that the public won’t be as receptive to angry rhetoric and incitement as they have been in the past. It’s likely that Trump and Republicans realize that it is to their advantage to rise above the mud-slinging that has been directed at them, rather than to angrily answer back.

That was also reflected in the decision of the Democrats to withdraw their political advertising that targets Trump, and Biden’s attempt to calm the waters in his speech to the nation on Sunday, even though his remarks were carefully written to try and cast as much blame on Republicans for the current atmosphere as possible.

Another was the decision of MSNBC to take their “Morning Joe” program off the air for the week following the attempt on Trump’s life. “Morning Joe” is reportedly Biden’s favorite television show, though the program was once actually quite friendly to Trump during the early months of the 2016 presidential campaign.

But it has been a perpetual in-kind contribution, not just to Biden’s re-election campaign, but to the effort to demonize Trump as a criminal authoritarian. While, as social media revealed, the move outraged its fan base who felt it deprived them of their daily fix of Trump-hatred, the network clearly thought that allowing it to air under these circumstances would bolster criticisms that its programming had incited violence against him.

If, indeed, the temperature is about to be lowered in public discourse, it’s all to the good. But it needs to be understood that the current political climate in the United States is unique in American history. Democrats have derided the right for what they’ve termed a “narrative of victimization.” But their campaign of lawfare directed against Trump, with its attempt to both bankrupt and imprison him, is unprecedented and redolent more of banana republics or totalitarian and authoritarian states than that of American democracy. While each successive president of both parties in the last three decades has inspired their own derangement syndrome, the one surrounding Trump has been the worst.

The extreme invective against Trump hasn’t come from marginal figures. The “Trump is Hitler” meme has been driven by liberal political commentators on mainstream and cable-news networks and legitimized by publications like The New Republic, which featured a portrait of the former president as Hitler on the cover of its June issue devoted to smearing the GOP as attempting to inaugurate an era of “American fascism.”

Contrary to Times opinion writer David Firestone, this isn’t merely “sharp language” or “normal political criticism.” Once you go down the rabbit hole of Hitler comparisons, discussions about the legitimacy of violence not only become more prevalent; they are rendered defensible, since they invoke counter-factual fantasies of how history could have been changed for the better had only someone been able to kill the Nazi leader prior to his launching of the Second World War and the Holocaust.

Nor did the assassination attempt entirely damp down this kind of toxic commentary. Beyond the gaslighting from liberals about everyone’s being guilty for making the crime possible, a willingness to view the event through the most cynical of lenses was also not confined to the political fever swamps. The day after the shooting, the leftist Jewish paper The Forward’ published an article devoted to explaining the attempt to murder the former president as a “Reichstag Fire” event in which the GOP, like the Nazis, was using a crime to justify its suppression of democracy.

That a supposedly responsible Jewish newspaper, edited by a former Jerusalem bureau chief of The New York Times, would bolster a conspiracy theory in this manner isn’t just outrageous. It’s a sign of how difficult it will be to dial down the rage on the left even after the shooting.

Still, we should hope that the reality of political violence will tamp down the impulse on the left to justify its own “insurrection” against the election results, whether by riots, such as those that occurred in the summer of 2020, or legal machinations, if Biden is defeated.

Trump’s narrow escape from death, and triumphantly defiant attitude after it, may well solidify the trend that had him leading Biden even before last month’s debate, an advantage that only grew after the Democrats turned on each other, as many of them sought to replace the president on their ticket. If a Trump victory in November is now more likely, the events in Butler should stand as a warning that it’s time to stop treating contemporary America as a replay of Weimar Germany, as Jewish Democrats did in one 2020 anti-Trump ad.

Their warning that “Charlottesville” —a reference to the 2017 neo-Nazi rally— “was happening all over America” under Trump was ironic, since on Biden’s watch, the surge of Jew-hatred has reached a point where one could say with justification that we’ve experienced thousands of Charlottesville-style moments of antisemitic violence and intimidation.

In the next four months, we will see whether it is indeed possible to pull back from the brink and return to a more normal political life in which disagreements or even controversial candidates are not treated as an excuse for a “Civil War,” as one dystopian Hollywood liberal film fantasy that came out earlier this year illustrated.

I remain convinced that most Americans don’t view the world from the same perspective of “Morning Joe” pundits or the op-ed page of The New York Times—or even the most rabid pro-Trump conservatives. The fact that Trump is leading a race that many Democrats have said all along he has no right to participate in may be a sign of pushback against the legitimization of that point of view and the accompanying lawfare campaign, as much as a judgment on the qualifications and positions of Trump or Biden. If Butler can put an end to the “anyone I don’t like is Hitler” style of political commentary, then at least some good can come out of a tragic moment in American history.

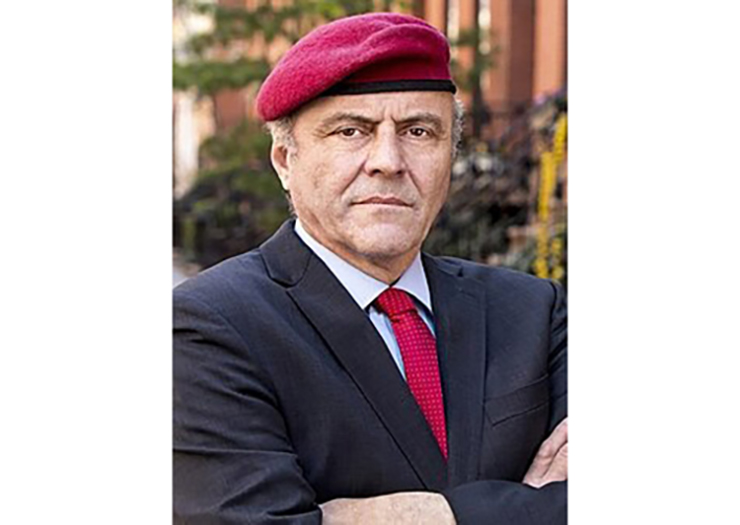

By Jonathan S. Tobin