Question: Should a person only learn what he enjoys?

Short Answer: While learning what you enjoy has special power, there are certain limits to this principle.

Explanation:

I. Topics To Learn

The Shulchan Aruch (Yoreh Dei’ah 246:4), based on the Rambam who understands that a person is learning nine hours a day, holds that a person should spend a third of his day learning Torah, a third of Mishnah (explanation of Torah), and a third of Gemara (reasoning behind the halachos). After he progresses in his learning, he may spend the bulk of his day learning Gemara. The Rama adds that what we call “Gemara” nowadays is sufficient to satisfy all three types, even at the beginning of a person’s learning.

The Shach (5) cites the Drishah who holds that a person learning just three hours a day should not only learn Gemara, Rashi, and Tosafos, but should make sure he devotes time to learn straightforward halachah.

II. Loving Learning

The Gemara (Avodah Zarah 19a) states that a person only learns “from a place” that he wants to learn from. Rashi explains that this means that a rebbi should teach his student the masechta of the student’s choosing, as the Torah will remain with the student when he learns a topic he enjoys or is interested in learning. This fits with the next story in the Gemara, where Levi looked for an excuse to leave shiur when they were not learning what he wanted. Rabbeinu Chananel has a slightly different girsa: a person only learns what his heart desires.

Both Rashi and Rabbeinu Chananel are clear that there is an inyan to learn what you want. What are the guidelines of such a concept? How does it fit with the Shulchan Aruch (above), which sets direct guidance on what a person should learn?

III. The Sefer Tachlis Chochmah

The sefer Tachlis Chochmah (Rav Aharon Zev Gottesman, p. 176-177) addresses this question. He strengthens his question based on the 1700’s sefer Sheivet Musar who writes that, practically, a person should only learn what he desires. Indeed, it is likely that the topic he desires to learn stems from a previous neshamah who failed to learn this topic and now is a gilgul to learn this topic. So, how come the Shulchan Aruch rules that you should split your learning into three parts, seemingly regardless of whether you want to learn these topics? Further, the Shulchan Aruch HaRav (Talmud Torah 2:1) codifies this tripartite learning schedule.

The Tachlis Chochmah suggests that perhaps this machlokes is based upon a similar machlokes: what a person should learn on Shavuos night. Some Acharonim hold he should learn Torah SheB’al Peh, while others hold he should specifically learn the Tikun designated for Shavuos night. He cites the Or L’Tziyon who explains that they disagree whether the rule of learning what you desire (i.e., Torah SheB’al Peh) is trumped by some other reason, here, the importance of Tikun. According to those who hold that it can be trumped, so too, the tripartite system trumps learning what you desire.

Regardless, the Tachlis Chochmah suggests that perhaps these two concepts – learning what you want and the tripartite system – are not contradictions. Within each part of the three, a person may choose which sefer to learn based on what he desires. In other words, you can learn Maseches Megillah instead of Z’vachim. Indeed, the Chayei Levi (10:131) appears to agree, as he rules that the “learning what you desire principle” means that a person may choose whether to begin a new masechta or to “chazer” the old masechta again.

IV. Other Answers

This author suggests a few more answers, based on certain limitations to this principle of learning what you desire, as found in sifrei Rishonim and Acharonim.

First, Rashi (Avodah Zarah, ibid) appears clear that this principle only applies in the context of a rebbi teaching a student. This is similar to the answer of the Tachlis Chochmah, that the principle only applies with respect to choosing which masechta to learn. Moreover, Rav Lazer Yehudah MiPshaworstock (cited in B’didi Hava Uvda, p. 300-301) further limits this principle: It only applies when the rebbi and talmid want to learn different masechtos, but of the same genre. Certainly, if a rebbi wants to learn Maseches Shabbos but the talmid wants to do Z’vachim, Shabbos takes precedence because it includes halachos – which fits with the Shulchan Aruch’s tripartite system.

Second, the Meiri (as cited in Avodah B’rurah, Avodah Zarah, p. 413) writes that the principle of learning what you desire only applies at the start of each learning session or topic. The Avodah B’rurah elaborates based on the Chofetz Chaim, who wrote that Rabbi Yisrael Salanter said that a person should skip parts of a masechta that he finds uninteresting when starting to learn a topic, and come back to them when he is more interested. See also sefer Nefesh Chayah (p. 166).

Third, the Aruch HaShulchan (Yoreh Dei’ah 246:17) notes that even though the Shach and others hold that one should learn Gemara and poskim in order to fulfill the tripartite system, one should not stop baal-habatim who insist on simply learning their one daf a day (without halachah). He implies that the reason for such leniency is that if they are forced to learn halachah – something they are not interested in learning – they will learn nothing at all. Accordingly, perhaps the “learning what you desire principle” is only a b’dieved for people who otherwise would not learn at all. Similarly, Rav Harfenes (Yisrael V’Oraisa, p. 293) learns that it is only a b’dieved, if you are not matzliach at learning what you are supposed to, you may learn aggadeta or other learning you desire.

Fourth, Rav Shmuel Genuth shlita (MeiRei’ach Nicho’ach, 5773, p. 863) cites the Steipler who understood that a person has the ability to learn what he desires during bein ha’zmanim, when there is less of a “requirement” to learn and one is not bound to a set structure of learning.

Fifth, the Vilna Gaon (Megillas Esther 1:8) explains that this “learning what you desire principle” only applies l’asid lavo, in olam ha’ba. In other words, in olam ha’ba, our reward is that we will learn and understand our favorite part of Torah.

V. Application To Children

Does this “learning what you desire principle” apply to children?

The sefer Michtam L’David (cited in Avodah B’rurah, ibid) holds that it does not apply, as a child has no “daas” to decide what he desires.

On the other hand, Rav Chaim Segal (Gam Ani Odecha, p. 184) holds that you may learn Torah with a young child on Erev Tish’ah B’Av, because otherwise the child won’t learn anything. Certainly, the child is not interested in learning the “bad topics” normally learned on Tish’ah B’Av, and thus the “learning what you desire principle” trumps him not learning. Rav Segal apparently holds that this principle applies to young children as well.

VI. Final Words

The Chofetz Chaim (Sheim Olam, perek 13) shares a beautiful idea. The phrase “v’sein chelkeinu b’Sorasecha” that we recite in davening means that every person davens that we are fortunate to uncover the hidden portion of Torah that is reserved uniquely for us. This is the part of Torah that we will desire the most. In other words, we must introspect to discover what area of Torah to which our hearts are most drawn, thereby enabling us to pursue such area and achieve our goal of learning “chelkeinu b’Sorasecha.”

Separately, the P’nei Menachem of Gur (cited in Daf al Daf, Avodah Zarah 19a) notes that the word “she’libo” is roshei teivos for “v’atah banim shiru la’melech,” highlighting that the key point is that the learning be with joy and happiness.

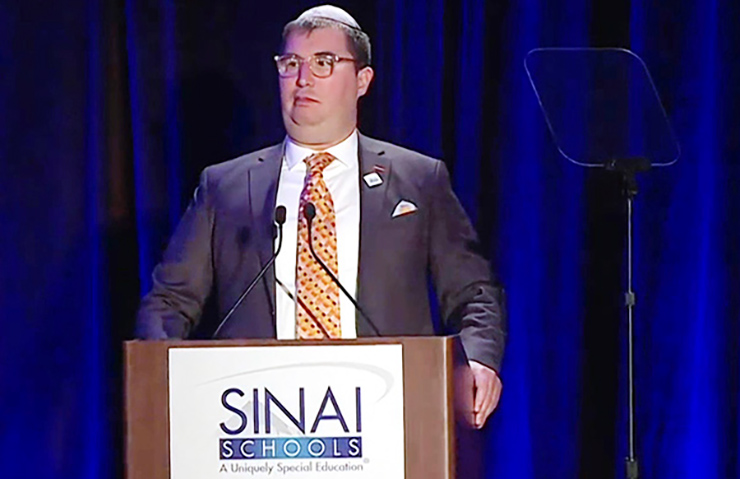

Rabbi Ephraim Glatt, Esq. is the Associate Rabbi at the Young Israel of Kew Gardens Hills, and he is a Partner at McGrail & Bensinger LLP, specializing in commercial litigation. Questions? Comments? Email This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it..