It was customary for people to travel to Radin to consult with the Chofetz Chaim, Rav Yisroel Meir Kagan zt”l, on any and all matters pertaining to Jewish life and halachah. In his later years, the Chofetz Chaim was quite old, and most people could not get more than a few minutes to spend with the tzadik, although they will tell you that those few minutes were worth more than the greatest treasure in their lives. Reb Leib, the son of the Chofetz Chaim, relates one notable exception. A talmid chacham came to Radin and asked to spend the holiday with his family; the Chofetz Chaim agreed to allow the man to stay.

On the first day of the holiday, the Chofetz Chaim was infused with simchah and spoke a great deal of Torah and words of musar to his scholarly guest, delving deeply into subjects pertaining to ahavah and yir’as Hashem (love and fear of Hashem). Throughout the day, however, the man hardly uttered a word in response. He would simply listen and nod his head, seeming to signal that he agreed with what he was hearing. Those present, including Reb Leib, thought that perhaps the man was not able to grasp the depth of meaning in the Chofetz Chaim’s words. The next day, however, to their surprise, the guest reviewed almost every point that the Chofetz Chaim had made the day before, and together with the tzadik, they discussed the subjects even more thoroughly, expanding upon what was said the previous day, and elaborating further.

The third day, though, was a repetition of the first. The guest simply sat there listening, barely saying a word, and occasionally nodding his head as if in agreement. In turn, day four was like day two. Once again, the talmid chacham seemed to spring to life. He discussed with the Chofetz Chaim everything that had been said on the previous day, and then added and expounded the points further. So went the cycle for the rest of the holiday: The man seemed to be “on” one day and “off” the next day.

The members of the Chofetz Chaim’s household thought that the guest’s behavior was very strange, and after he had departed, Reb Leib asked his father what it all meant. Rav Yisroel Meir smiled and explained everything by means of a parable.

In rural villages, each homeowner plants his own vegetable garden next to his house, and builds a protective fence around it. Sometimes, the fence is not high enough, so it fails to stop goats and other animals from jumping into the garden and doing damage. Seeing the problem, he builds the fence higher. If it happens that, one day, someone in his household forgets to close the fence’s gate, and as a result an animal gets in, he scolds the negligent one, including a warning to be more careful about keeping the gate closed in the future. If animals continue to intrude, what will become of the vegetable garden, which is a major source of sustenance for the entire family? What happens if the same thing happens over and over again, until the sheep and goats of the town feel at home inside the fence? The homeowner has no choice but to board up the gate, so that when someone or another has to enter the garden, there is no choice but to jump over the fence. It is a bother, true, and very inconvenient. As a result of the jump, there is also a risk of falling hard, spraining an ankle, or getting pricked by a thorn. Still, the homeowner feels he has to take such an extreme precaution as no one in his household can guarantee that the gate will not be left open again!

So it is, explained the Chofetz Chaim, regarding the needs of the human soul. Guarding one’s tongue is an essential need of the soul. A man can foresee all sorts of problems arising from not guarding his tongue properly. Frivolity can sneak in, nivul peh (filthy language), as well, not to mention the very real occurrence of lashon ha’ra and r’chilus. To prevent damage to his soul, he builds a protective fence around his mouth, to guard what comes in and out. If he sees that the steps he is taking are not “tall” enough, he decides upon a more drastic measure, in which he sets aside times when he only listens and thinks, and does not speak at all. This type of “fence” carries difficulties and, with it, all sorts of discomfort and even embarrassments, because he often has to resort to winks, hand signals, and body movements to communicate and signal his understanding. Still, since he cares for his soul, he is not afraid, for it is worth such inconvenience to avoid the damage to his soul that can come from words spoken without proper consideration. Better to suffer embarrassment in this world than in the next world!

Reb Leib concluded: In the end, we learned that the talmid chacham came to ask for advice about the yeshivah he was opening and, with wisdom, skill, and yir’as Shamayim, for which he became renowned, his yeshivah grew into a fabulous mekom Torah.

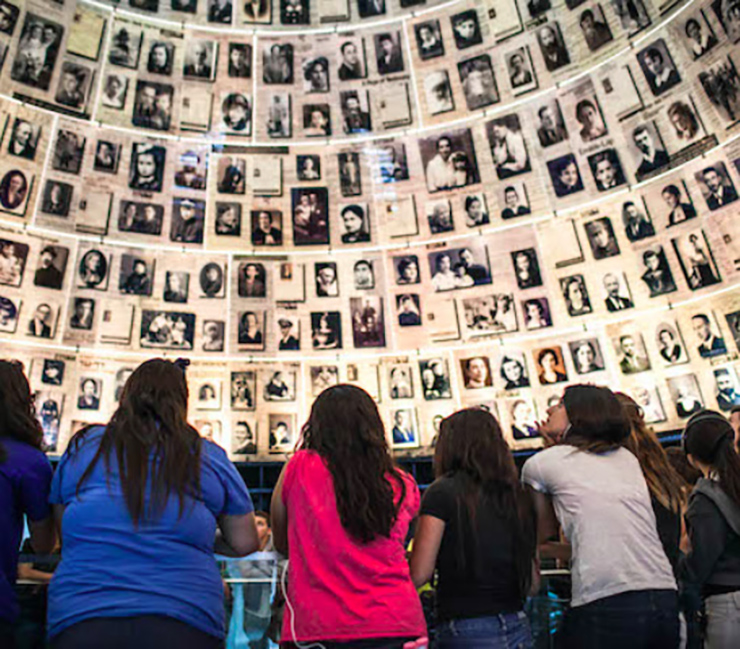

Rabbi Dovid Hoffman is the author of the popular “Torah Tavlin” book series, filled with stories, wit and hundreds of divrei Torah, including the brand new “Torah Tavlin Yamim Noraim” in stores everywhere. You’ll love this popular series. Also look for his book, “Heroes of Spirit,” containing one hundred fascinating stories on the Holocaust. They are fantastic gifts, available in all Judaica bookstores and online at http://israelbookshoppublications.com. To receive Rabbi Hoffman’s weekly “Torah Tavlin” sheet on the parsha, e-mail This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.