In the “world’s borough,” every language can be heard, and for Jewish languages, the epicenter of this diversity is Rego Park. I experienced it in my youth, in which the barber spoke Bukhori, the baker spoke Hungarian, the rabbi spoke German, elders spoke Yiddish sprinkled with Romanian and Ukrainian words, classmates spoke Russian, and many other such anecdotes within a short walking distance.

Manashe Khaimov recognized the proximity of these linguistically diverse restaurants, shuls, and businesses as an opportunity to highlight endangered Jewish languages.

“I’ve been giving walking tours in Rego Park since 2017. The idea is to touch all five senses. You hear it from the musician, touch it in the museum, smell and taste it in a restaurant, and see it all around,” he said. “We had a lot of students and academics on this tour, 45 participants in total.”

An adjunct professor of Jewish history at Queens College, Khaimov founded SAMi, the Sephardic American Mizrachi Initiative to promote the cultures of non-Ashkenazi Jews on college campuses. His tour of Rego Park last month was in partnership with the Jewish Language Project, an initiative of Hebrew Union College.

“It is an effort to document all the Jewish languages around the world,” said Sarah Bunim Benor, the project’s founding director. “We had experts speak of their efforts to document Judeo-Shirazi, Judeo-Isfahani, and Judeo-Georgian.”

The first two of these were the result of the immigration wave that arrived in Queens following the 1979 revolution in Iran. To outsiders, their language was Farsi, but among Persian Jews from certain cities and regions, there were words and phrases specific to those places. Likewise with Georgian Jews, whose speech is understood by ethnic Georgians while it includes elements of Hebrew and Aramaic.

“Are they languages or dialects? It’s open to debate. It’s about mutual intelligibility. To me it doesn’t matter. It’s the way that Jews have spoken Georgian throughout history,” Benor said. “I’m interested in how they insert Hebrew words, as a secretive measure. It’s worthy of analysis.”

Khaimov’s tour usually ends at the Bukharian Jewish Museum, founded by Aron Aronov inside the Jewish Institute of Queens. The collection began in Aronov’s basement more than 20 years ago, and with support from philanthropist Lev Leviev, space was allocated for his collection within the yeshivah on Woodhaven Boulevard. Because Aronov was not available this time, the museum was skipped, but there was plenty to see across so-called “Regostan.”

“We visited the Rokhat bakery on Austin Street where we saw how tandoori bread is made. We showed them the ovens and explained kashrut,” Khaimov said. They then went two blocks east to the Paras synagogue on 67th Avenue. “They initially did not want the attention of a tour group.”

Fortunately, the group included fluent Farsi speakers, including Habib Borjian, a scholar of Iranian languages who contributed towards the online Encyclopedia Iranica project. “He published a short booklet on the Bukharian language, and he spoke about Persian Jewish languages such as Teherani and Shirazi.”

Inside the oldest Persian synagogue in Queens, Khaimov noticed a lot of mirrors. “It’s the influence of Persia and Zoroastrianism, reflecting back and kicking out the evil eye. It was good that we had a Persian speaker in our group.”

Sam Miller was born in Rego Park, where he heard his grandparents and uncle speak Lishan-Didan, the Jewish Aramaic dialect of northwestern Iran. “My mother is a fluent speaker; she grew up in Urmia. She left in 1986, as soon as they started issuing travel visas to get out. The family claimed that it was a vacation, with a two-way ticket. An organization helped them receive asylum on religious persecution grounds, and they settled in Queens,” Miller said.

They davened at the Sephardic Jewish Center on 67th Drive, which is led by Rabbi Sholem Ber Hecht, who helped thousands of Persian Jews immigrate to New York following the 1979 revolution. Miller lamented the loss of minhagim as Jewish immigrants either assimilated into the secular culture, or blended into larger streams within Orthodoxy, such as modern, yeshivish, or Chabad. He spoke of preserving Lishan-Didan on academic and personal grounds.

“There is a scholarly aspect to it, adding to the general knowledge base of humanity. As a speaker, it is important to me for cultural continuity. It’s paying respect to my ancestors. This language is my inheritance.”

His father is Ashkenazi, which he said gives him perspective from the cultural majority and minority. “I’m an AI researcher, that’s my day job. At night, I document endangered languages and I want to bring them together. I want to keep these languages alive.”

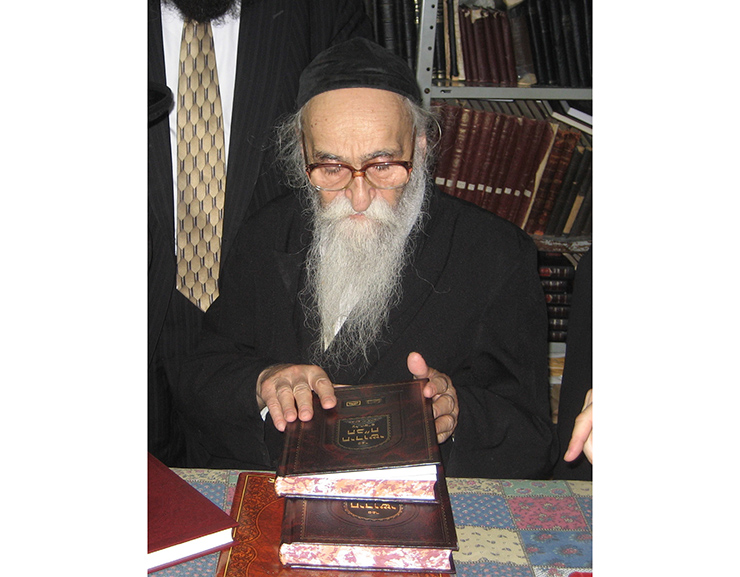

At the Bukharian Jewish Community Center in Forest Hills, the tour group could not go inside the beis k’neses, as there was a l’vayah taking place; so Khaimov took them to the fifth floor offices, where paintings of Bukharian rabbis lined the hallway. “I was asked by tour participants if they are arranged by chronology or geography. It’s very Ashkenazi to have structure,” he said.

The tour finished with lunch at Art of Grill next to the 63rd Drive subway station. While they waited for the food, the interior offered a feast for the eyes, with pointed arches, latticework, and carpet-like tapestries hanging on the walls. “I try to give a chaykhana type of feel,” Khaimov said, referring to the Central Asian tea houses where people meet. “A lot of connections came out of it, the desire to collaborate and work on college campuses.”

Among other scholars who took the tour with Khaimov were Ross Perlin of the Endangered Languages Project, Wikitongues cofounder Daniel Bögre Udell, and Tamriko Lomtadze, who studies the Jewish dialect of the Georgian language.

“Young people are interested, but there’s not enough access to the information,” Khaimov said. “Every day, I get a message about a book, or a family, and it’s not for school; it’s for their own personal research.”

By Sergey Kadinsky