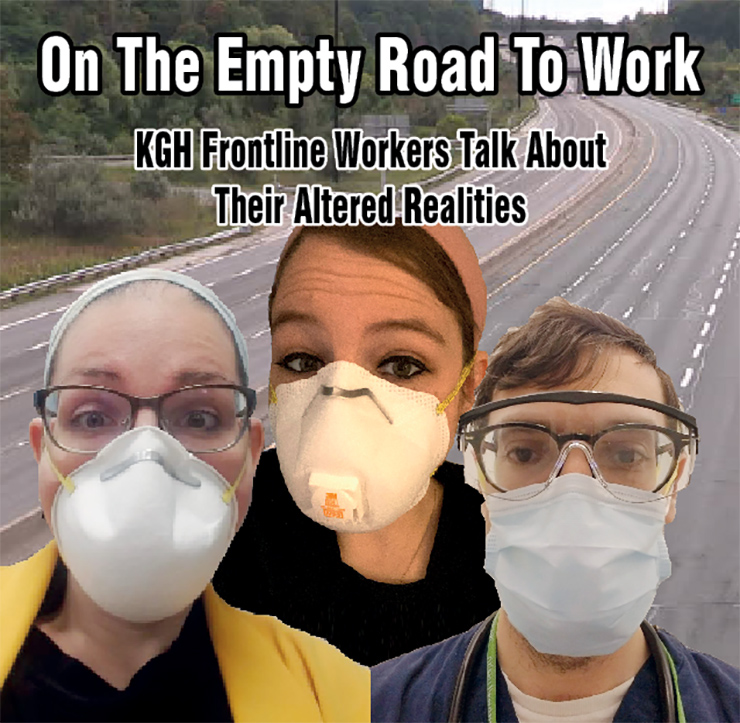

When highways across the city have electronic signs with messages urging the public to stay home, Zev Nirenberg rushes from Kew Gardens Hills to his office in Brooklyn. He looks at the other drivers on the road and wonders how many of them are essential workers with occupations directly connected to combating the coronavirus pandemic. “Where are they going?” he asks. “What are they doing?”

Nirenberg is a pharmacist at an infusion pharmacy, where staff size has been reduced, and those remaining on site work in 12-hour shifts. “You never see your colleagues. You leave them notes and messages.” On the home front, his wife Gabriella balances working at home with the coursework of their two daughters.

Perel Lubel Saklad also lives in Kew Gardens Hills and takes the commute on nearly empty roads to the Montefiore Hospital in the Bronx, and its affiliated facilities. “I provide creative wellness for hospital staff and new mothers. I hear the trauma that they are experiencing. It is a lot to hear every day,” she said.

Saklad works as an art therapist, hearing the fears of medical professionals who work on the frontline of the virus, and in turn developing and speaking about her own fears. “We recently had training from a therapist who went to war zones to conduct mental therapy. It is like a war. The scariest thing is that we do not know why some people get it.” After a long day of work, she returns home, showers, changes her clothes, and catches up with her husband Shmuely. “When I drive, Waze sends messages not to drive unless absolutely necessary. It feels weird that I am not staying at home.”

Ariella Goldhammer must leave home to provide infusions to her clients. She initially described the experience of a traffic-free commute as a novelty; but it is also tiring, as it includes disinfecting three times daily after meeting with each patient. “I work in a small room and can only see two patients at once, where it was previously three or four,” she said. “I disinfect myself between each patient. My clientele is immunocompromised.” The toll that the work has taken on her is the fear that any action could result in a positive diagnosis – for example, turning a doorknob, or being too close to an infected individual. Her husband Marc works from home and takes care of their two daughters.

Moshe Verschleiser never experienced the ease of commuting from Jewel Avenue to Borough Park in half an hour, describing it as the most positive element of his workday. “I manage a home for adults at Ohel,” he said. “We serve dinner in two shifts; the staff wear masks and take their temperatures,” he said.

Nearly two months after workplaces across New York began shutting down, Verschleiser shared his fear that anyone could be a carrier of the virus. “I personally was not feeling great after Purim, but the symptoms that I had were not those for COVID-19. I tested negative.” Later, he was tested for antibodies that develop as a result of the virus and was found to have them. “It takes a toll on care providers. You know what’s waiting for you the next day and it’s not getting any better,” Verschleiser said.

He mostly misses the social life that has been upended by the quarantine. “My social life is at home,” he said. His wife Chaviva supervises their two sons and their online learning, while balancing her own work from home as an occupational therapist. “The kids hear everything. They know the news. They’re stressed, and they ask questions.”

Dr. Yoni Garellek commutes east, splitting his work between the Northwell-affiliated Long Island Jewish Hospital in New Hyde Park and North Shore University Hospital in Manhasset, working as an infectious disease fellow. “Usually we all share an office and discuss specific situations,” he said. “Now you can’t have lunch with a colleague. We have media platforms for communicating.”

Eight weeks into the quarantine, Garellek said that from his experience, and as noted by Governor Andrew Cuomo in his daily presentations, the number of infected New Yorkers is flattening. The number of vacant beds has increased, and patients are coming in for problems unrelated to the virus, but nobody knows when the “plateau” will decrease in a sustained manner for enough days to satisfy lifting the quarantine. At home, Garellek’s wife watches their three children. “The change in learning has been hard for them,” he said.

These are only a few of the drivers whose presence on the road is related to their essential work of keeping fellow New Yorkers healthy during the pandemic. They are all married and have children, with their own set of difficulties adjusting to the quarantine. Readers who miss the commute and break from children can be thankful for having the time to personally educate them when other parents cannot, as a result of their designation as essential workers.

By Sergey Kadinsky