On Wednesday evening, April 27, Dr. Rafael Medoff, historian and author, shared a virtual lecture to commemorate Yom HaShoah in memory of Martin Dov Berger.

Mr. Ephraim Berger emceed and introduced the speakers. Rabbi Yoel Schonfeld, rav of the Young Israel of Kew Gardens Hills, greeted everyone and introduced the program. He shared that action from American Jews was needed during the Holocaust and they did not rise to the occasion.

Rabbi Shmuel Marcus, rav of the Young Israel of Queens Valley, spoke next. He noted that when Jews of Satmar returned to their shul after the war, the shul was intact, amazingly, and, on the wall, the parshah was Acharei Mos-K’doshim: fitting words for what happened during the Holocaust. He shared that “with shuls in Queens coming together in achdus, we should merit to live holy lives because we come together.” We remember the lives of k’doshim to inspire us to live lives of k’dushah.

Next, Dr. Medoff related that, in 1943, 400 rabbis marched to Washington, DC. We are used to 1960s Civil Rights protests in Washington, the anti-war movement protests, and the rallies for Israel and for Soviet Jews. The idea of Jews protesting at the White House is more recent. This is why people are surprised that during the Holocaust (1941-1945) there was only one Jewish march to Washington. However, he pointed out that it was a consequential march. It was omitted from popular accounts of the period. “It was in a sense written out of history.”

The Jewish community’s knowledge of this march is a recent phenomenon. Many family members of the rabbis who took part didn’t know that their father or zeide took part in the march. In the 1940s, American Jews did not stage public protests in Washington. It was an atmosphere of open anti-Semitism, and Stephen Samuel Wise, Reform rabbi and Jewish political and Zionist leader, felt it was inappropriate for Jews to publicly protest President Roosevelt’s policies. Wise was a big admirer of FDR and close to the Democratic Party.

The idea of a march came from a Zionist activist named Hillel Kook (also known as Peter Bergson) who was raised in British Mandate Palestine. He was a nephew of the Chief Rabbi, Rav Kook. Bergson didn’t have the manpower to organize a march of rabbis. He recognized the need to shatter the curtain of silence around the Shoah. He sponsored newspaper advertisements and lobbied in Congress for help to save the Jews in Europe. In 1943, he turned to the Vaad Hatzalah, which was associated with the Agudath Israel of America. These were mostly European rabbis who spoke Yiddish. They supplied the manpower for the march.

In 1943, during the week leading up to Yom Kippur on October 6, 400 rabbis participated in this march on Washington. The trip from New York to Washington, DC, in those days was slower and more arduous. Going right before Yom Kippur was also a difficult time for rabbis to travel, since it’s a busy time for them. Their goal was to impress President Roosevelt with the urgency of the situation in Europe for Jews.

Jewish War Veterans participated as honor guards, and the only other Jewish organization that helped was Hadassah. No other Jewish organization cooperated. Some were opposed to this form of protest.

The rabbis marched from Union Station to the Capitol. They were greeted by Congress members and the Vice President, Henry Wallace. Rabbi Eliezer Silver read a petition at the Lincoln Memorial. The petition asked for food shipments and a request for a special government agency to act at once on a large scale to rescue the Jews trapped in Europe. At the Lincoln Memorial, they sang the National Anthem and HaTikvah, and they recited a prayer for American soldiers in Europe.

The main obstacle for Jews to come to America to escape the Nazis was the polices of the President, which were implemented by the State Department. The laws for immigration were strict and harsh and made it impossible to come.

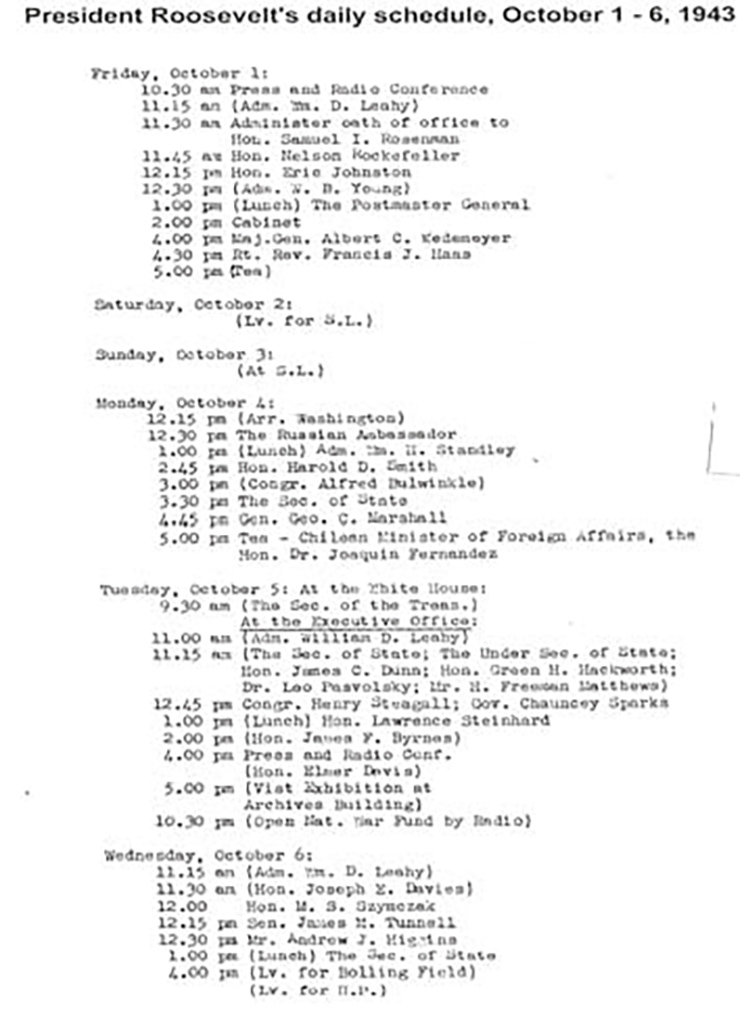

After the Lincoln Memorial, the rabbis marched to the White House. Most of the participants waited across the street, and a small delegation went to seek a meeting with the President. Before the march, telegrams were sent to secure the meeting. The President was the target of the march. It is clear from his schedule that day that he had ample time to meet with the rabbis. He was free from 1:00 p.m. until 4:00 p.m. that day, but he chose to leave the White House through the back exit and avoid them. They were told by a low-level official that President Roosevelt was too busy to meet with them.

His primary reason for avoiding them was that if he met with them, he would draw attention to their cause. He didn’t want to give them prominence or respect, as it would mean pressure to do more to help Jews.

In the diary of the President’s Post War Secretary, William Hurst, he wrote that on October 6, the President knew about these rabbis coming and he wouldn’t see them.

Judge Samuel Rosenman, the chief advisor to the President on Jewish affairs, felt it was inappropriate for Jews to petition the President. He told the President that this group was not representative of the most thoughtful element of Jews and that the Jewish leaders of his acquaintance opposed this march. He found their appearance embarrassing.

The day after the march, the headline in the Washington Times Herald was: “Rabbis Report Cold Welcome at the White House.”

At that time, the Jewish community supported President Roosevelt. Eighty percent of American Jews voted for him. So, this criticism by the rabbis was remarkable. The delegation was deeply disappointed by what had happened. They left feeling their mission was a failure because the President refused to meet with them. “The above-mentioned article and others made the march a success.” The President saw this press coverage and suddenly this issue of Jews challenging the President was in the public eye.

Dr. Medoff explained that politically this march was significant. The press coverage of it sent out a ripple effect. In 1944, the Bergson group went to congressional leaders and requested they introduce a resolution to create an agency to rescue Jews in Europe. This congressional lobby by Bergson set in motion events that FDR couldn’t stop. At the beginning of 1944, the rescue issue was a subject of controversy and discussion. It was hashgachah pratis that, at this time, senior aides to Henry Morgenthau, Jr., Secretary of the Treasury, discovered that the State Department had been suppressing news about the Holocaust and stymying rescue efforts. In June 1944, Morgenthau asked Congress to create a new agency. He pleaded for it.

FDR was a master politician. Politically, he realized he had to do something for the Jews, so in January 1944, he created an agency, which is what the 400 rabbis had wanted. It was called the War Refugee Board. FDR was forced to do it. He only gave it token funding. Ninety percent of the funding came from the Joint Distribution Committee. This agency enlisted Raoul Wallenberg to rescue Jews. It funded his work. Clearly, the process of events leading to Wallenberg rescues includes the march of the 400 rabbis.

Dr. Medoff shared that he has a list of 250 rabbis who were on the march. “I interviewed a handful of surviving marchers ten years ago,” Dr. Medoff stated. He recorded eight oral interviews. Rabbi Levi Horowitz, the Bostoner Rebbe, was one of the interviewees. He went to the march with his father. There are 12 existing photos of the march. (See photos). He was 18 years old, and they had not registered in advance, so he wasn’t listed.

The Bostoner Rebbe explained why families didn’t know that their family member had participated in the march. Part of the reason was that they were humble, and part was that they felt they had failed because the President snubbed them. They didn’t know how the march was really connected to the formation of the War Refugee Board. He shared that the march had an impact on him. In 1967, when Israel was under attack, he thought about that march in 1943, and he realized he needed to do something like that again. He hired buses and urged his congregants to go with him to Washington to pressure President Johnson to help save Israel. Many people had come for a rally, and when they arrived in Washington, just as they left the buses, they heard the news that Israel had won the war. The rally turned into a celebration, with Jews of all types joining hands and dancing near the White House.

Dr. Medoff shared that in the 1940s there were immigration quotas, but there were 200,000 slots from Germany that were never even filled. He added that a rabbi like Stephen Wise had an obligation to do everything he could to rescue Jews as a leader of a Jewish organization.

He noted that there were many anti-Semitic remarks in the diaries of government officials of that time period. There was a broad dislike of foreigners. Some 130,000 Japanese citizens were rounded up into camps during that time.

Rabbi Marcus led T’hilim in memory of the k’doshim. Following this, Mr. Kenny Mittel, vice president of the Young Israel of Queens Valley, led the singing of “Ani Maamin.” It was an extremely meaningful and informative program.

The program was sponsored by the following shuls of Kew Gardens Hills: Agudath Israel of KGH, Bais Medrash of KGH, Bais Yosef D’Ulem, Congregation Chasam Sofer, Congregation Etz Chaim, Congregation Ohel Yitzchok, the Jewish Heritage Center, the Young Israel of Kew Gardens Hills, and the Young Israel of Queens Valley. The program was also sponsored by the Queens Jewish Link and the Bukharian Jewish Link.

By Susie Garber