Shortly before Rosh HaShanah, I read an article entitled, “His Best Friend Was a 250-Pound Warthog – one day it decided to kill him.”

It told the story of Austin, who lives on a ranch in Texas. Austin loves animals and has spent years caring for them. But there was one animal that Austin invested in more than any other: Waylon the warthog. From when Waylon was born, Austin felt deeply connected to him. “I just kinda became his parent – his dad, really. Early on I’d take him to the drive-thru at Whataburger, and he’d sit in the front seat, happy as can be.” Austin loved to play with Waylon and Waylon would often fall asleep on Austin’s stomach.

Warthogs are not predators and will usually not seek confrontation. But if they feel threatened, they will use their speed – they can run up to 30 mph – agility, and strong tusks to attack effectively.

The article ominously noted that “Experts say a reputation for docility can be the very quality that makes a particular animal dangerous.” One unremarkable October day, Austin entered the enclosure and scratched Waylon’s back. Waylon then trotted alongside him to a nearby feeding trough. By all indications, Waylon was his usual playful self. However, when Austin began walking towards his car, parked at the gate, he suddenly felt his right leg crumble and he was thrust forward 15 feet.

I’ll spare the rest of the unpleasant details, but Waylon had unexpectedly entered murder mode and was attacking relentlessly. Waylon viciously gored Austin about 15 times. By the time Austin was brought to the hospital, he had lost almost half the blood in his body. It took doctors eleven surgeries to repair the damage to his body. Obviously, Waylon had to be put down afterwards.

The article concludes with a quote from Austin: “I don’t think it was Waylon who attacked me. I was attacked by a warthog.”

Since I read the story during the “t’shuvah season,” I had an interesting reflection from the story.

Human beings are a composite of a neshamah (soul) and a guf (body). A body without a soul is just a lifeless mass of blood, bones, and organs. It is the soul that gives it the spark of life.

On the other hand, a soul cannot “live” in the physical world without a body. Although what defines us is essentially our soul, our body enables us to live in this world.

The Gemara (Chagigah 16a) notes that a human is like an angel in three ways and like an animal in three ways. Humans have knowledge, walk upright, and speak in lashon ha’kodesh like angels. But humans also eat and drink, procreate, and excrete like animals.

The sefer M’silas Y’sharim compares the soul-body connection to a peasant who marries a princess. Despite his best efforts to prepare his greatest delicacies for her, she will be unimpressed. He simply cannot relate or match up to the royalty she is accustomed to.

Our bodies enable us to connect with others in this world, actualize our aspirations in life, and function in this world. Still, we must never forget that the body is a loose cannon. If we keep it under control and ensure that we properly discipline ourselves, our bodies will be our most valuable asset, our best friend. However, if left unbridled and given free rein, our body can lead us into a dangerous abyss, and we can drastically hurt ourselves and others physically and spiritually.

A century ago, a mere handful of evil individuals – Hitler, Stalin, Mao, Pol Pot, etc. – were responsible for the deaths of tens of millions of people. They may have been born with souls, but their bodily desires led them to the nadir of humanity.

In contrast, the Midrash (D’varim Rabbah 11:10) relates that when the time came for Moshe Rabbeinu to die, his soul didn’t want to part from his body. Even after Hashem promised Moshe’s soul that it would ascend to the highest heights, it begged Hashem not to be separated from Moshe. Finally, Hashem removed the neshamah against its will and Moshe died.

Moshe had lived his life with so much discipline and had raised himself to a level of holiness that his holy neshamah was completely comfortable remaining with his holy body.

My rebbi, Rabbi Mordechai Finkelman, Mashgiach of Yeshiva Ohr HaChaim in Queens, notes that he often encourages parents to ensure that their children are adequately protected from the dangers of technology. This includes ensuring that any electronic device is adequately filtered. Parents will sometimes counter that they trust their child. In addition, children themselves will often strongly protest efforts to filter or set limits on their devices by accusing their parents of not trusting them. Rabbi Finkelman’s reply is poignant: “Trust your child. But don’t trust your child’s yeitzer ha’ra!” Even the best of people have an inner force that can cause devastation if not monitored and guarded.

It’s no less true for our own yitzrei ha’ra.

The heartbroken Austin was only able to make sense of the tragic end of Waylon by reasoning that it wasn’t Waylon who tried to kill him, but a warthog. But at the end of the day, a warthog can be no more than a warthog, no matter how pleasant it may seem to have been for so many years.

If we allow our bodies free rein to pursue their whims and lusts, we can become degenerate and dangerous people.

On the other hand, we have the capacity to attain greatness and holiness. Doing so means that we contend with our physicality. Although we cannot negate our body, we can channel its drives and desires productively and become wonderful people – not despite it but because of it.

The choice is ours!

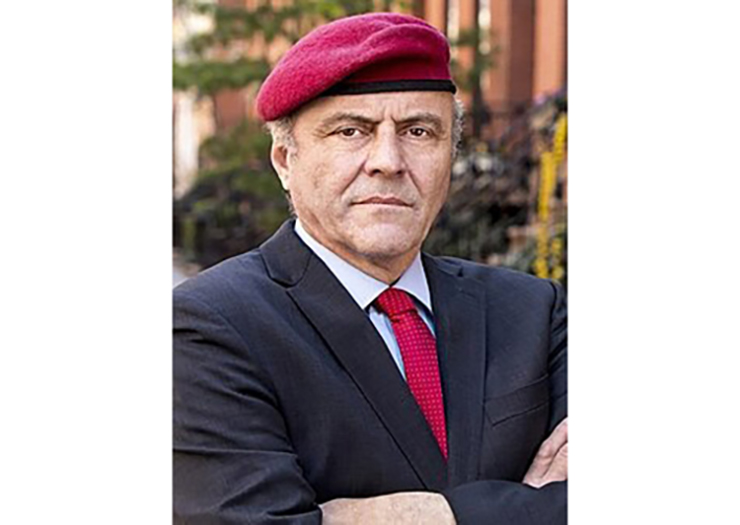

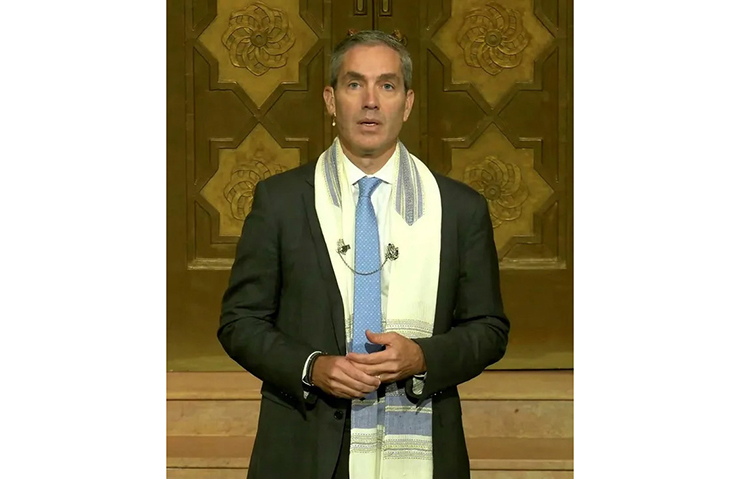

Rabbi Dani Staum, LMSW, is a popular speaker, columnist, and author. He is a rebbe at Heichal HaTorah in Teaneck, NJ. and principal of Mesivta Orchos Yosher in Spring Valley, NY. Rabbi Staum is also a member of the administration of Camp Dora Golding. He can be reached at This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it. and at www.strivinghigher.com