Our children are often told that growing up entails becoming more mature. I occasionally ask my students and my children how they define maturity and what it means to them. Their answers are varied and sometimes they can’t really pinpoint what it means to them.

A colleague of mine, who is a seasoned educator, recounts a personal story to new incoming students at the beginning of each school year.

A while back, he was the dean of an out-of-town school. One evening, the local township placed a stop sign outside the school. The next morning, a police officer sat outside in his cruiser, waiting for the first person to run the new, unexpected stop sign. Obviously, it didn’t take long.

One student on her way into class was pulled over on school property. The dean saw the flashing lights, heard how gruff the cop was speaking to his student and saw that his student looked crestfallen. He walked over to her to offer moral support. The officer immediately lashed out at him to get away, but he replied that he just wanted to make sure his student was okay. When the officer repeated that the dean had to immediately leave, he replied that he would do so as soon as he knew the officer’s badge number. That, he admits, was a big mistake.

A moment later he found himself being thrown against the police cruiser, arm raised and handcuffed. He was then thrown into the back of the cruiser. Meanwhile, students and parents were pulling into the school parking lot, trying to figure out why in the world their school dean was being arrested like a criminal.

He was driven to the police station where he was put into a large jail cell with many other inmates. Late that night, he was finally released, and the overly aggressive cop was reassigned to desk duty.

When he was first led into the cell, the other inmates asked him the classic number one jail question: “What are you in for?”

When he explained that he was interfering with a traffic ticket, they hardly believed him. But the part that amazed him, and that he would share with his students, is that he seemed to be the only one who did anything wrong. Every other inmate in the cell, after noting what he was accused of, would insist that he was completely innocent, and was mistakenly arrested or framed. Even the guy with clear blood stains on his shirt, accused of murder, insisted he hadn’t done anything, and they arrested the wrong guy.

After sharing this story, my colleague looks out at the students and notes that they have not come to school that year simply to learn academics, but also to grow as people. An important part of that growth entails taking responsibility. Even when one falls short of his expectations, he must be able to admit to it and assume responsibility, so that he can grow from the experience.

This is the point I convey to my students and my children, as well. An integral component of maturity is taking responsibility and not looking to shift the blame.

Rav Samson Rafael Hirsch explains that the Jewish idea of viduy – confession – does not entail confessing to another person, or even to G-d. Rather, it is an admission to oneself that he has come up short in his responsibilities. In order to say viduy, one must first get past his natural defenses and excuses. “Only if we have the courage to censure ourselves, to consider our blemished past with the same attribute of honesty with which it is viewed by G-d, only then is there hope that we will realize our resolutions and fulfill our duty in the future.”

It is not shameful for one to sin. In fact, to err is as natural as being human. The Torah and the Gemara are replete with statements and stories that demonstrate this. What is shameful is when one cannot fess up to what he has done and refuses to take responsibility for his actions or their consequences. That is a telltale sign of immaturity. Leadership begins with maturity and the courage to assume responsibility and not shy away from it, even when there are challenging consequences.

On February 1, 2001, during the Second Arab Intifada, Dr. Shmuel Gillis, 42, a prominent hematologist and father of five, was shot and killed while driving home from work. Ten days later, Tsachi Sasson, 35, father of two, was also shot and killed while driving home on the bridge between Yerushalayim and Gush Etzion. Both were murdered by Arab terrorists.

In their memory, their widows founded Pinah Chamah – The Soldier’s Corner (literally: The Warm Corner). It is a place where soldiers can rest and relax and enjoy some free refreshments, and a cold or hot drink, provided with a smile.

Pinah Chamah is maintained by volunteers and supported by donations.

In April 2010, I had the great fortune to join an Orthodox Union Rabbinical Mission to Israel together with 25 rabbis from across America.

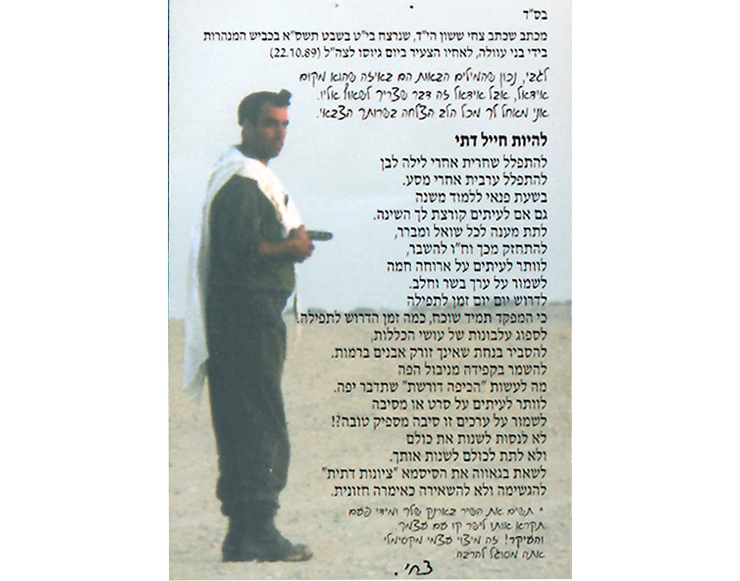

One of the places we visited was Gush Etzion, which included a stop at Pinah Chamah. While there, I noticed a small, printed card with a picture of an Israeli soldier and a Hebrew message. The picture was of Tsachi Sasson, and the message was a letter he had sent to his younger brother Gabi on the day of his induction into the IDF in 1989.

I was very inspired by the message, and I kept the card.

The following is my loose translation of the letter. (I hope it’s accurate.)

*****

To Gabi,

It’s true that the following message is somewhat ideological. But we have to strive for high ideals. I wholeheartedly wish you success during your army service.

To Be a Religious Soldier

To daven Shacharis after a white night[1]; to daven Maariv after a journey.

During free time to learn Mishnayos, even when you feel tired.

To reply to anyone who asks questions or wants clarification, to become strengthened from it and not, G-d forbid, to feel broken.

At times, to forgo a hot meal in order to adhere to the laws forbidding mixtures of meat and milk.

To seek out time for prayer every day, because the commanders often forget how much time prayers require.

To bear the shame of those who make the rules, and to explain that you don’t throw rocks.

To be particular not to use foul language, because wearing a kippah on your head demands that you speak pleasantly.

At times, to forgo watching a movie or attending a party to maintain greater values

Not to try to change everyone around you and not to allow everyone around you to change you.

To bear the title “Religious Zionist” with pride, to live up to it and not allow it to be just a theoretical concept.

Place this card in your wallet and read it periodically to refocus yourself.

The main thing is to demand the most from yourself. You are capable of great things.

Tsachi

*****

Tsachi’s sense of mission and dedication to his values is exemplary. The Army itself commands discipline. But a religious soldier has the added responsibility to be dedicated to his values and the demands of halachah.

His words remind me that I, too, must have that level of dedication and sense of responsibility. I, too, need to view myself as a soldier with a mandate to be uncompromisingly loyal. I, too, must strive to be a mature person despite living in a world of immaturity, always casting blame and aspersions. I, too, must be able to bear responsibility for my mishaps and shortcomings, so that I can be a leader within my own family and community.

It is this attitude and mindset that has maintained the Jewish people throughout history. It is through the tireless contributions of great individuals who have undertaken the responsibility to preserve and perpetuate the Torah. It is how we have returned to Eretz Yisrael after centuries in exile, and how we continue to thrive there despite the odds and daily challenges. It is how the Torah world was rebuilt from the ashes and restored the crown of Torah in Eretz Yisrael.

We view ourselves as soldiers, proud members of the Army that cannot, and will not, ever be defeated.

Rabbi Dani Staum, LMSW, a rebbe at Heichal HaTorah in Teaneck, New Jersey, is a parenting consultant and maintains a private practice for adolescents and adults. He is also a member of the administration of Camp Dora Golding for over two decades. Rabbi Staum was a community rabbi for ten years, and has been involved in education as a principal, guidance counselor, and teacher in various yeshivos. Rabbi Staum is a noted author and sought-after lecturer, with hundreds of lectures posted on torahanytime.com. He has published articles and books about education, parenting, and Torah living in contemporary society. Rabbi Staum can be reached at This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.. His website containing archives of his writings is www.stamTorah.info.

[1] - I assume that means a night without sleep