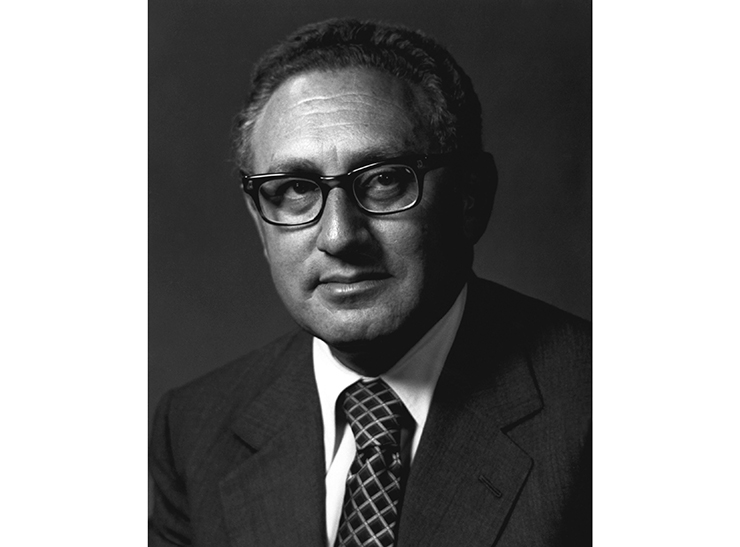

Henry Kissinger, who died last week at the age of 100, was the first Jewish Secretary of State and arguably the most powerful Jew in American history. But was he good for the Jews?

Heinz Alfred Kissinger was born on May 27, 1923, in Furth, Bavaria, Germany. His parents, Louis and Paula (Stern) Kissinger were observant Jews who tried to raise him to become a loyal member of the shul in Furth. His parents saw the handwriting on the wall in the Hitler years and immigrated to the United States in 1938. They settled in the largely German Jewish neighborhood of Washington Heights and joined the world-famous Khal Adath Jeshurun, led by Rav Joseph Breuer zt”l. With his first name Americanized to Henry, he attended George Washington High School and City College before being drafted into the Army during World War II. To this very day, there is a plaque in the Breuer’s shul that includes Henry Kissinger on the Honor Roll of member of the kehillah serving in the military. While Kissinger as an adult was no longer religiously observant, he always showed great respect for his parents and made it a point to attend family religious events like the Pesach Seder. He spent much of the war and its aftermath in Germany working on intelligence. He returned in 1947 and enrolled at Harvard.

Before 1969, Kissinger was primarily an academician and author. He appeared often on television as an “expert” on foreign affairs. This brought him to the attention of President Richard M. Nixon, who appointed him as National Security Advisor. He was the Nixon administration’s key point man on foreign policy. In 1973, the position of Secretary of State was added to his portfolio, making him the only person to hold both top foreign policy positions in the executive branch.

Kissinger is best known for his role in the opening to China and détente with the Soviet Union. But he also had an enormous impact in the Middle East.

Early in his administration, President Nixon supported the plan of his Secretary of State William P. Rogers for an Israeli withdrawal to the pre-1967 boundaries. Kissinger convinced President Nixon that a strong Israel was in America’s best interest. It was at this time that the United States became Israel’s main weapons supplier. At the same time, Kissinger was telling Egypt and other Arab states that only the United States could get Israel to make concessions.

On the morning of Yom Kippur, October 6, 1973, Israel was taken by surprise when the Egyptian Army crossed the Suez Canal into Sinai. Israeli intelligence had carefully observed Egypt’s military maneuvers but told the government that Egypt was unlikely to launch a full-scale war. By the morning of Yom Kippur, it became obvious that war was imminent. Kissinger spoke to Prime Minister Golda Meir, telling her that if Israel refrained from launching a preemptive strike, it could count on US support. The message was clear. If Israel did launch a preemptive strike, there would not be American support. Prime Minister Meir would later say that the need to retain American support was critical in her decision not to launch a preemptive strike.

James Schlesinger, who was Secretary of Defense at the time, said that Kissinger told him, “The best thing that can happen for us is for the Israelis to come out ahead but to get bloodied in the process.” With that in mind, he delayed resupplying Israel with military equipment. Sensing the possibility of an Arab victory, the Soviet Union launched an airlift to resupply the Egyptian and Syrian armies.

At first, the war went badly for Israel. Prime Minister Meir thought the end of the Third Commonwealth was near and considered committing suicide. Anxious to stave off Israeli defeat, Kissinger tried to get America’s allies to propose a ceasefire, to no avail.

By this time, President Nixon was consumed by the Watergate scandal and the resignation of Vice President Spiro Agnew. Kissinger was effectively in charge of American policy.

With Israel on the brink of defeat, three of Israel’s closest friends in the US Senate, Henry Jackson of Washington, Hubert Humphrey of Minnesota, and Ed Brooke of Massachusetts, met with President Nixon and urged him to act immediately to resupply Israel. After the meeting, Kissinger told the Senators that he was a Jewish refugee from Nazi Germany and would never allow Irael to be destroyed.

A massive airlift to resupply Israel helped turn the tide of the war. Forces led by General Arik Sharon broke through the Egyptian lines in Sinai, crossed the Suez Canal and encircled the Egyptian Third Army. Israel was turning near catastrophe into a clearcut victory. The Soviet Union threatened to intervene on behalf of the Egyptians. The United States put its armed forces on alert. The hotline between Washington and Moscow, which was designed to provide for instant communication between the United States and the Soviet Union, to prevent misunderstandings that could lead to nuclear war was used for the first time. Kissinger traveled to Moscow where a cease fire was announced. The cease fire prevented Israel from winning a more sweeping victory.

The Yom Kippur War ended the way Kissinger hoped it would, with Israel victorious but bloodied.

After the war, Kisinger conducted shuttle diplomacy between Israel and Egypt and Syria. Under the first separation of forces agreement with Egypt, Israel pulled out of Egypt and moved back from the Suez Canal. The disengagement agreement with Syria provided for an Israeli withdrawal from the part of Syria that was occupied during the Yom Kippur War and from the city of Quneitra in the Golan Heights.

Kissinger’s next attempt was to arrange for an Israeli withdrawal from the strategic Mitla and Gidi passes in Sinai and the Abu Rhodes oil fields. Israel refused to withdraw without a non-belligerence agreement with Egypt. By this time, Gerald Ford had become President. He and Kissinger announced a “reassessment” of American policy towards Israel, a thinly veiled threat that Israel had better get with the US-sponsored program. A few months later, Israel agreed to the proposal it had earlier rejected.

Kissinger was not always a friend of Israel. His forcing Israel to refrain from launching a preemptive strike on Yom Kippur of 1973 and his delay in resupplying Israel led to significant Israeli losses. His timing in arranging the cease fire deprived Israel of winning a clear-cut victory.

Yet Kissinger did come through for Israel when it meant the most. The airlift of American supplies was critical to turning the tide of the Yom Kippur War. The alert of American forces prevented the Soviets from intervening in the war on the Egyptian side.

After the Six-Day War, the humiliated members of the Arab League proclaimed the “three no’s”: “No peace with Israel, no negotiations with Israel, no recognition of Israel.”

By orchestrating an end to the Yom Kippur War that enabled Israel to survive while restoring Arab pride, Kissinger paved the way for Anwar Sadat’s historic visit to Jerusalem and the first peace treaty between Israel and an Arab country. Israel gave up the Sinai. But the largest Arab army was taken off the battlefield.

One of the things for which Kissinger is best known is for détente with the Soviet Union. A battle between two Henrys, Kissinger and Jackson, over the connection between détente and the right of Jews to leave the Soviet Union would dramatically transform the Jewish world.

By Manny Behar