Part 3

Continued from last week

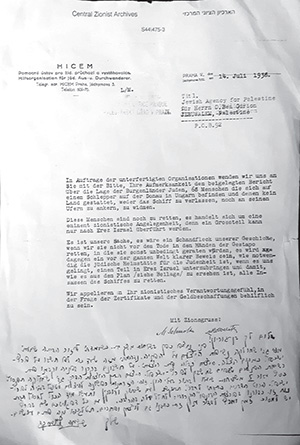

After being evicted from their homes and from their country, the Jews of Kittsee were forced to live on a rat-infested barge for five months, after which they were transferred to a detention camp in Budapest. While they were in Budapest, the workers at HICEM, HIAS, the Jewish Agency, and the American Joint Distribution Committee made efforts to find countries that would be willing to take in these homeless refugees. The families had to prove that they were upstanding people and would not be a burden on society.

Some of the families immigrated to what was then known as Palestine, others to England. My father’s family was able to get mail to my grandfather’s sister who lived in New York at the time. My great-grandparents were very unhappy when their daughter had left Europe to begin a new life in the “treife medina.” But that was yet another example of hashgachah pratis, as it was critical that they had someone advocating on their behalf on the other side of the ocean. My father’s aunt worked tirelessly for their release and, with great effort on her part, she was able to procure visas and arrange for my father’s family to immigrate to the United States. My family was eternally grateful for what my father’s aunt had done for them. No family simchah of my childhood was complete without an expression of hakaras ha’tov to Tanta Perela, without whose efforts it is possible that none of us would even be here today. The family set out from Trieste, Italy, and arrived in the United States in November of 1939 on the SS Saturnia, one of the last ships to leave Europe before the war. A total of 18 months had passed from the time they were forced to leave their home in Kittsee.

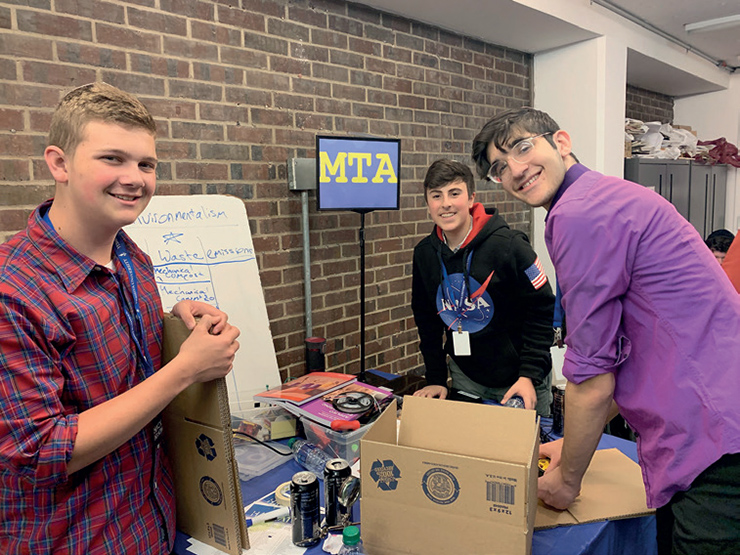

Upon their arrival in New York, the Schapiros lived on the Lower East Side. But after a few short months, my grandparents and their four children – Joseph (my father), Genie, Asher, and Rachel – moved to Spring Valley. My grandfather took a position there as a chazan and a shochet. In those days, there was very little Jewish presence in the area. It was more of a vacation town. My aunts and uncle had no choice but to attend the local public school. One day, shortly before Pesach, my uncle came home from school with painted Easter eggs. That was a turning point. At that moment, my grandfather decided that he must open a school so that his children could get proper chinuch. That is how the Yeshiva of Spring Valley was born. My grandfather was the spiritual leader and guide of the Yeshiva as well as the first rebbe. My grandmother was also very involved in the school in its early stages. My uncle remembers many meetings dedicated to the planning and development of the Yeshiva, which took place around their dining room table. My grandfather was very much involved in all chinuch aspects of the school until his sudden and tragic p’tirah in 1945 at the young age of 42.

In 1973, my father’s mother passed away. One of her final requests was that my father travel to Vienna to visit the kever of her father, for whom my father is named. Two years later, on their way home from Israel, my parents stopped off in Vienna for the day. My father’s experiences there, as a child, prevented him from being willing to sleep there for even one night. First, they took a bus to the cemetery. The Vienna cemetery is huge. My parents asked to be let off at the Jewish entrance but were told that the bus doesn’t even stop there. They got off at the nearest entrance and walked the rest of the way. It took quite a bit of time to find the kever of my great-grandfather. Nobody from the family had been to the kever in over 35 years. When they found it, my father took out a pocket knife and began cutting the overgrown weeds that hid the grave. They said T’hilim and then set off for the shul in Kittsee where my father had lived. Although my father remembered the town well, when they got to the spot where the shul should have stood, it was nowhere to be found. They found a different building standing in its place. When they went to the town hall to inquire about the fate of the shul, they met the Burgomeister (mayor), Mr. Konrad Frey. He explained that in 1950 the building had been demolished. He then asked my father what his name was, as he, too, had lived in Kittsee before the war.

“My name is Schapiro,” answered my father.

“Schapiro? I remember a Schapiro. He was the town shochet and he had four children,” recalled the Burgomeister.

“That is correct. And I am the oldest son,” answered my father.

When the Burgomeister heard that, all of the blood drained from his face from shock. He was quick to explain that although he lived in the town at that time, he most certainly was not involved in harming any Jews. From that moment on, the Burgomeister gave my parents the royal treatment. He took them around in his limousine and showed them some of the sites of Vienna. My father asked if the caretaker of the shul was still alive. He was told that he had already passed away but that his daughter, Resi, was still living in Kittsee. The Burgomeister drove my parents to Resi’s house. When Resi’s daughter answered the door, my father introduced himself and explained who he was. My father thought the daughter was just being polite when she said that she knew exactly who he was. But it turns out that she really did. Her mother had spoken to her family about the Schapiros very often over the years. Resi’s daughter said that her mother had traveled to Vienna for the day. My father left an old family photo with her and drew an arrow pointing to himself so that Resi would know which Schapiro had come by.

Several weeks later, my father received a letter from Resi. She had been waiting for so many years to be reunited with the family and was sorely disappointed that she had missed his visit. Had she known that he would be coming, “wild horses could not have dragged her away from her home.” She recalled the beautiful times that the families shared in the happy years before the war. Who knew then what the future would bring? She remembered the z’miros that my father’s family sang. She wrote that the Nazis auctioned off the possessions of the Jews after they threw them out of their homes. Her father had bought whatever he could afford of our family’s belongings in the hope that one day he would be able to give them back to us. Resi still had some of those objects in her home and had been waiting for someone in the family to come back to Kittsee so that she would be able to return them to their rightful owners.

My father and Resi continued to correspond with each other for a short time, filling in one another about the years that had passed. One day, my father received a phone call from a stranger asking my father to meet him as he had a package for him. My father met the man who then presented him with the tea set from his home in Kittsee. Resi had sent it with the man when she heard he was traveling to New York and begged him not to let it out of his sight for one second until he had hand-delivered it to my father. He was very happy to be relieved of his package.

In 2010, my husband and I went to visit Vienna. We, too, went to the kever of my great-grandfather, another 35 years after my parents had been there. We also visited Julia, one of the caretaker’s daughters who was still alive at the time. She had very vivid and fond memories of my family, which she shared with us. She sang a Jewish song that my father had taught her over 70 years before. I had heard so much about the shul in Kittsee but I had never seen a picture of it. Julia had a picture of the shul hanging on her wall. Even though she wasn’t Jewish, her memories of the shul and the families who lived there were very close to her heart. She took the picture right off the wall and gave it to me.

The story of the Jews of Kittsee was documented in newspapers and was known all over the world. We don’t understand the ways of Hashem, but we do know that all Hashem does is for the good. When the Jews of Kittsee were thrown out of their homes and were not accepted into any country, I am sure they questioned why they had to undergo such hardships. They most certainly wished they could have returned to their homes and to their previous lives. But unbeknownst to them at the time, their forced expulsion is in actuality what saved them, by enabling them to escape Europe before it was too late. I shudder to think what their fate might have been had events not unfolded as they did. Rabos machashavos b’lev ish; va’atzas Hashem, hi sakum.

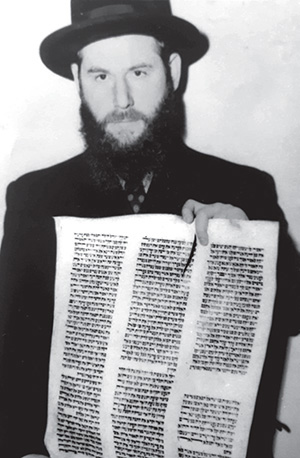

Somehow, my grandfather had been able to smuggle a sefer Torah out of Vienna and bring it to the United States. The Nazis had slashed the sefer Torah with a knife, exactly on the words, “v’chaasher y’anu oso, kein yirbeh v’chein yifrotz” – “but the more they [the Egyptians] oppressed them, the more the Israelites proliferated and spread” (Sh’mos 1:12). The Jews of Kittsee were similar to the Jews of Mitzrayim in this way. The more they suffered at the hands of the Nazis y”sh, the more they increased and grew stronger. Klal Yisrael was dealt an extraordinary blow during the Shoah, but baruch Hashem, we survived as a nation and continue to persevere and flourish.

Suzie (nee Schapiro) Steinberg grew up in Kew Gardens Hills. She works as a social worker and lives with her husband and children in Ramat Beit Shemesh.