A couple of years ago, I wrote about an imagined future for Iraq in which Rabbi Paysach Krohn leads Jewish heritage tours of Pumbedisa and Sura, with the same descriptive expertise as his tours of Poland and kivrei tzadikim closer to home in Queens. Unfortunately, this hypothetical learning experience has yet to become reality. Likewise, the entirety of Eretz Yisrael has not been brought under Jewish control, with Gaza as the hornet’s nest of terrorism that kidnaps and murders Israelis and rains rockets on population centers. But what if the near future made it possible for Jews to visit Gaza safely as tourists? What would they see?

“We have crossed the Green Line and are heading directly to Gaza City for the earliest evidence of Jewish life in this territory,” the tour guide said. “Until now, the only digging that took place here were the tunnels used to smuggle weapons and hide hostages, but if we peel back the layers of history, we will find evidence of Jewish history in Gaza City.”

“Gaza and its environs are absolutely considered part of the Land of Israel,” Rabbi Yaakov Emden wrote in his sefer Mor u’Ketiziah in the 1660s. “There is no doubt that it is a mitzvah (commandment) to live there, as in any other part of the Land of Israel.”

The armored bus entered the outskirts of Gaza City, where residents looked at the bus not with hatred but regret, the same feeling that Germans had as they walked among the ruins of Berlin in 1945. Their “thousand-year reich” went down in flames and their sense of moral superiority was shattered by images of death camps, far from German cities, out of sight and mind to the average citizen. But for the Gazans, images of Jews dying was common knowledge, accessible to anyone with a mobile phone and an Internet connection.

In contrast to the 13-year duration of the Third Reich, anti-Semitism in Gaza festered for more than 75 years, fed by a permanent refugee status that promised return to Israel once it is wiped off the map, sustained by the international community that financed schools that taught anti-Semitism, a government that rewarded “martyrdom,” and expectations that with each UN resolution they were one step closer to realizing their dream. But what if the Palestinians could, against the odds, come to terms with Israel and the role of Jews not as settlers or colonists, but as an indigenous nation that returned to its historic home?

“Our first stop is the Zeitoun neighborhood,” the guide said. Amid these tight alleys is St. Porphyrius, one of the oldest churches in Christendom. Throughout the Muslim world, sharia law segregated Muslims from nonbelievers. “If this is the Christian Quarter, surely there must have been a Jewish Quarter in Gaza. As there were in Jerusalem, Damascus, and Baghdad.”

The last members of Gaza City’s historic Jewish community fled from this city in 1929, when riots across British Palestine devastated Jewish communities. The most famous example was in Hebron, where 67 Jews were murdered, and the survivors were evacuated by British police. Less known were the smaller communities in Tulkarem, Shechem, Jenin, and Gaza City.

“They were put on a train to Lod. It was their ticket to survival,” the guide said. “After 1948, this small city ballooned into a metropolis for displaced Palestinians, and stories of the much smaller numbers of Jewish refugees displaced by Arab violence were forgotten.”

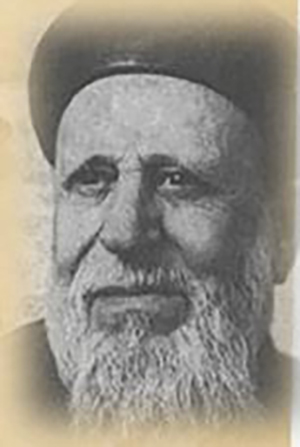

One of the travelers raised his hand. “If there were Jews living here, they must have had a synagogue, mikvah, and cemetery, testifying to their presence.” Gaza Chief Rabbi Israel Najara, author of the popular Shabbos song Kah Ribon Olam, is buried in the city’s long-forgotten Jewish cemetery, which was developed during the Egyptian occupation prior to 1967.

This guide opened a Hebrew language book, A Jewish Community in Gaza, published in 2020 by journalist Haggai Hoberman, a former resident of the Gush Katif settlements.

“The image of Gaza is that of a foreign, Philistine, Palestinian city. The juxtaposition of the Jews and Gaza does not quite add up in the mind,” the author said in an interview with Arutz Sheva shortly before the book’s release. “But if we go really far, the ancestors lived in Nahal Gerar, which is Nahal Gaza, and from the Hasmonean period there are Jews living in Gaza City itself.”

Assigned to Sheivet Yehudah, the coastal strip was a center of resistance to Jewish sovereignty as it is today. Next to Zeitoun is the Daraj neighborhood, the highest point in Gaza City. Its defining landmark is the Great Mosque, which was built on the site of a Byzantine church. In turn, that church was believed to be the site of the Philistine temple where Shimshon was held captive. His physical strength brought down the Temple of Dagon, killing everyone inside.

Returning to the former Jewish Quarter, the tour guide spoke about Nathan of Gaza, a mystic who had visions of Shabsai Zvi as the Mashiach. He made that declaration in the city’s synagogue. Failing to gain support from rabbis in Jerusalem, he declared Gaza as the new holy city. “Nathan later followed the false messiah to Turkey, but his name is always associated with Gaza,” the guide noted.

Returning to the Zeitoun neighborhood, the guide pointed out that the Jewish community in Gaza ebbed and flowed throughout the centuries, leaving the city and then returning when it became safe to do so. In the early 20th century, Gaza Chief Rabbi Nissim Binyamin Ohana had good relations with its leading Muslim cleric, Sheikh Abdallah al-’Almi. They co-authored a book Know How to Respond to an Apikores, as a response to Christian missionaries, who established a clinic in Gaza.

One of his granddaughters was married to the late Jewish Press columnist Steven Plaut. “A grandson of the mufti of Gaza...has served as the Hamas representative in Damascus,” Plaut wrote in a 2009 column on Jewish history in Gaza. “Some of Rabbi Ohana’s grandchildren in Israel are in possession of manuscripts written by the mufti. It is their hope that once Hamas is finally defeated and peace is established, the manuscripts will be turned over to the descendants of the mufti, Rabbi Ohana’s close friend.”

By Sergey Kadinsky