While Israel’s fight for its survival in the wake of the brutal terror assault on October 7 remains the focal point of headlines in recent weeks, it is also an opportune moment to reflect on pointed anniversaries this November. November 9-10, 2023, for instance, marks the 85th anniversary of Kristallnacht, “the Night of Broken Glass,” when German Nazis perpetrated a wave of violent Jewish pogroms all throughout Germany, and annexed Austria and part of Czechoslovakia in occupied areas of the Sudetenland. At least 91 Jews were killed as 7,500 Jewish businesses were vandalized and 1,400 synagogues destroyed. As recorded by Yad Vashem, up to 30,000 Jewish men were arrested, many of whom were taken to concentration camps like Dachau or Buchenwald. Many died in these camps. All of these horrific scenes were but precursors to the horrors of the Shoah, which was still years away.

Within a week of Kristallnacht, the British government allowed unaccompanied minors under the age of 17 from the German Reich, including the aforementioned annexed territories of Austria and Czechoslovakia, to enter Great Britain as refugees. Great Britain’s child welfare organizations arranged for the care of children upon arrival to the country. Their journey came to be known as Kindertransport. The plan, which took shape on November 15, 1938, was made whereby it became the responsibility of private citizens and specific organizations to guarantee payment for each child’s well-being. The first Kindertransport ship arrived at the port in Harwich, Great Britain, on December 2, 1938, and included around 200 children from a Jewish orphanage in Berlin. Most of the transports left from Berlin, Vienna, Prague, and Gdańsk. Some organizations and individuals participating in these rescue operations included Inside Britain and the Movement for the Care of Children. By 1939, Britain was home to over 60,000 Jewish refugees, 50,000 of whom settled permanently, as reported by the Holocaust Memorial Day Trust.

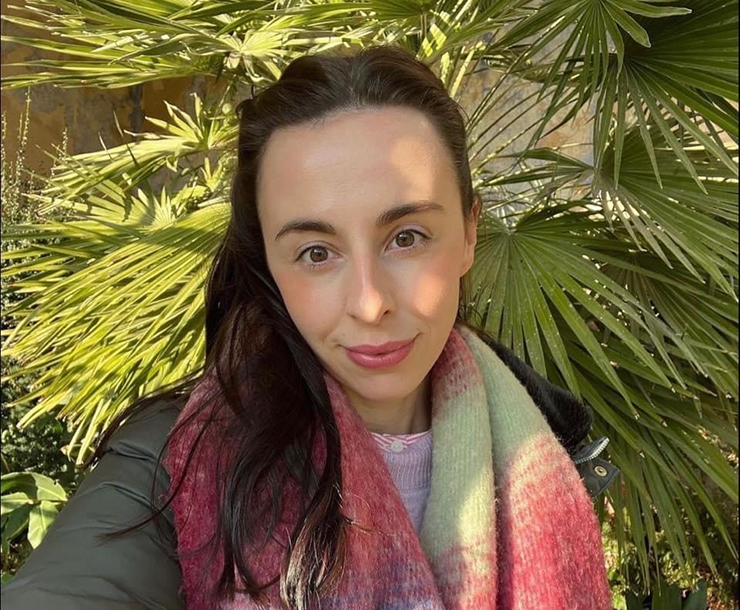

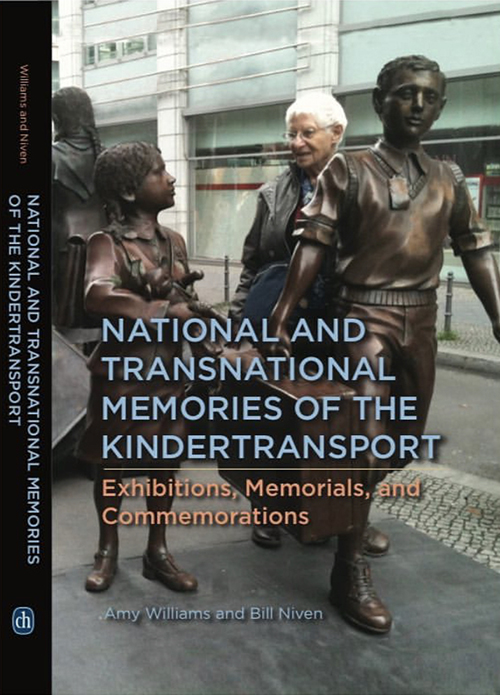

Dr. Amy Williams, a Birmingham, UK, native who currently serves as a Postdoctoral Fellow at the Zolberg Institute on Migration at the New School for Social Research in Manhattan, has co-authored a big volume on the subject with UK Professor Bill Niven. The book, which was published in August, titled National and Transnational Memories of the Kindertransport: Exhibitions, Memorial, and Commemorations, was co-written with Prof. Niven, who taught Dr. Williams during her undergraduate years while also supervising her dissertations. She credits him as her academic mentor. Speaking exclusively to the Queens Jewish Link, Dr. Williams has illuminated the importance and enduring legacy of this unique landmark and seminal touchstone within the annals of Jewish history.

“The splitting up of families because of Kristallnacht led many mothers to make the brave decision to send their children to strangers,” says Dr. Williams. “I’ve spoken with about 150 families from all over the world. Hanna Zach Miley [for instance] is a survivor who I speak with most days, and we have become great friends. We have learned so much from one another, and our friendship means the world to me. She is so inspiring, kind, and so open to talk about everything and anything with me. I’m so grateful for her presence in my life. All the survivors’ stories are so dear to me, [and] I am so thankful to them for sharing all that they do. Their determination to educate us is awe-inspiring, and their personalities and energies also encourage us to do more.”

Dr. Williams says she grew close to the subject of the Kindertransport since her father “was sent to Switzerland with the Red Cross when he was a child for health reasons. My grandparents had this old, battered suitcase in the loft with a little Red Cross logo on it. They also had letters, documents, photographs, and many Swiss objects around the house. When I was looking into our family story, I learned that Switzerland had a long history of taking in poorer children. The invitations to this country were part of a long-established humanitarian program. Similar visits involving French and Belgian children had taken place during the Second World War and continued into the late 1940s for displaced and refugee children across Europe. There was initially some discussion as to whether children from Britain should be invited to take part, because they did not fall into the same displaced category.

“This is essentially how I came to the Kindertransport [subject], as many ‘Kinder’ were helped by the Red Cross and taken to areas where my Dad stayed some 20 years earlier,” continues Dr. Williams. “These connections run deep for me [and my interest] grew because I spoke with the Kindertransport family. It is because of them that I am still researching this topic some ten years after my first degree. I always wanted to study this topic because I saw that there was a disconnect between how Britain remembered this historical event and the complex personal transnational memories of the survivors. My work aims to try to present the Kindertransport in all of its complexity.”

Dr. Williams is a member of the Kindertransport Association (KTA), a non-profit organization with chapters in Florida, California, and New York. Its mission continues to connect child Holocaust survivors with families and their descendants. “It means everything to be a member of the KTA, [as] I wouldn’t be able to do my work without them. They are incredibly supportive, and [many of whom have] become close friends. They also have put me in touch with many survivors and organizations, so I’m very grateful to them.” After the war ended, many Kindertransport children stayed in Britain or immigrated to the United States, Canada, Australia, and the newly formed State of Israel.

By Jared Feldschreiber