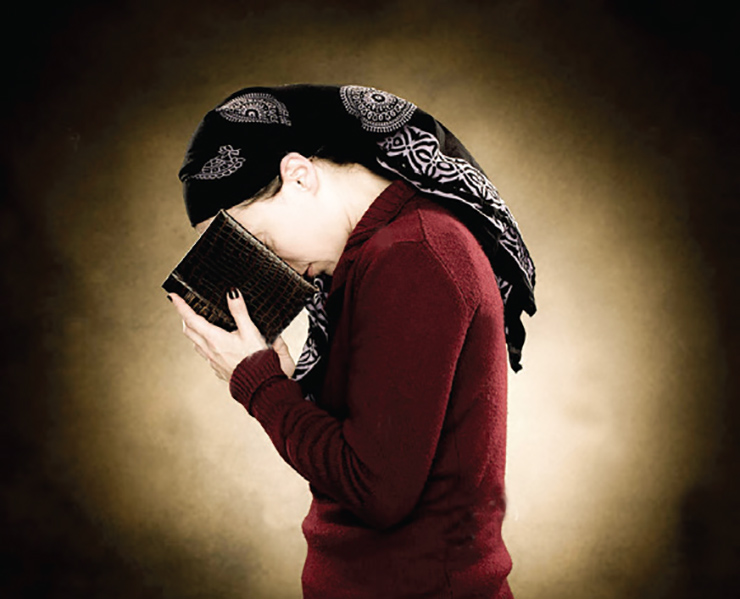

An old man sat with his grandson by the campfire, gazing into the dancing flames. With a sparkle in his eye, the old man looked at the young boy and began telling him a story. “Legend has it that there is a fight going on inside each of us between two wolves. One wolf is evil, filled with anger, envy, sorrow, regret, greed, arrogance, self-pity, guilt, resentment, inferiority, lies, false pride, superiority, and ego. The other wolf is good: He is joy, peace, love, hope, serenity, humility, kindness, benevolence, empathy, generosity, truth, compassion, and faith. These wolves are constantly at war, a war that rages on within each of us.”

The grandson thought about this quietly for a minute and then asked his grandfather: “Which wolf wins?”

The old man looked at his grandson and replied, “The one you feed.”

The Mateh: Good or Evil?

There is a principle in Jewish thought that many of the most fundamental aspects of Torah are expressed in the most deceptively simple manner. Our job is to delve into these seemingly mundane topics and reveal their inner depth and meaning. One such example is Moshe Rabbeinu’s mateh (his staff). It plays a pivotal role within the story of Y’tzias Mitzrayim (the Exodus from Egypt), and yet how often do we ponder its paramount significance?

The mateh first appears at the sneh (the burning bush), where it turns into a snake. (Sh’mos 4:3; see Rashi – Hashem turns it into a snake in Moshe’s hands in response to Moshe speaking lashon ha’ra about the Jewish People.) When Moshe confronts Pharaoh’s court, the mateh once again turns into a snake (Sh’mos 7:12 – Chazal equate the mateh of Aharon with the mateh of Moshe). In Jewish thought, the snake represents evil and the yetzer ha’ra (evil inclination), so it would appear as if the mateh represents evil.

However, the mateh is also used to perform all of the Makos in Mitzrayim (Sh’mos 4:17), as well as K’rias Yam Suf (the Splitting of the Red Sea) – the pinnacle of the miraculous, transcendent experience of Y’tzias Mitzrayim. Additionally, the Midrash explains that Hashem’s name was crystalized into the mateh itself. It therefore appears that the mateh is a very spiritual object, the exact opposite of the evil it seems to represent. What, then, is the true nature of the mateh?

Everything Is Potential

In order to understand the meaning of the mateh, we must first develop a fundamental principle. The Maharal explains that nothing in the physical world is objectively good or evil. Rather, everything has the potential to be used for either good or evil. The choice is solely up to us. This can be illustrated by a number of examples:

Electricity is neither good nor bad. An outlet can be used to charge your appliances, but it can also give you an electric shock.

The same applies to money: It can be used to enable Torah learning, but it can also be used to fund destruction and chaos.

A charismatic personality can be used to inspire others to grow or to seduce them down the wrong path.

Everything in this world is merely potential, waiting to be used. Evil, therefore, is the misuse of potential, when we choose to use an object for something other than its true purpose. Evil is the breakdown and corruption of good. This is why the Hebrew word for evil is ra, which means brokenness or fragmentation.

Hashem created the world in this way so that human beings can have free will. We get to choose whether to use things for their true purpose, actualizing their potential, or to misuse them, getting pulled into the clutches of evil.

The More Power, the More Potential

Having established that everything has the potential to be used for good or evil, it’s also important to realize that the more power there is, the more potential there is. For example:

A 110-volt outlet can either charge your phone or give you a small electric shock.

But 20,000 watts can either light up your neighborhood or electrocute you.

The point is: The more power, the more potential. Of course, this results in an important principle: The value in any power is only in as much as it can be controlled. Otherwise, the more power you have, the more destruction you will have, as we often see with nuclear energy and money. Just think about giving a child the power to cross the street by himself. When do you give him such a power? Only when he has the ability to control it, i.e., to know when not to cross the street.

The Mateh: Potential for Good or Evil

Now we can begin to understand the mateh. It is neither good nor evil. Its nature depends solely on the one who holds it. It can represent the nachash, the snake of evil, but it can also be used for spirituality, e.g., to carry out Hashem’s mission in this world. When in the form of evil, it causes Moshe to run away in abject terror; but when in the form of good, it enables the world to witness Hashem’s miracles. While this alone is an essential point, we can develop this theme even further.

The Bent Path and the Straight Path

The Midrash compares Mitzrayim and the nachash to a “bent path,” while the mateh symbolizes a straight path. What is the deeper meaning behind the concepts of the bent and straight paths?

Imagine you are walking along a straight path. At any point along the path, if you turn around, you can see exactly where you came from. However, if the path suddenly takes a sharp turn, bending off its straight course, then if you turn around, you can no longer see the starting point of your journey. The same is true of the physical world in which we live. Originally, the physical world faithfully and perfectly reflected its spiritual root. When you looked around, you saw and experienced Hashem, and you knew that He created the world; it was like looking back down a straight path. However, after Adam sinned, the entire world fell. The world became a bent path, and it is no longer clear where we come from. When we look around, we no longer see a universe that clearly and loyally reflects its G-dliness.

The nachash bends and slithers, representing a bent path, a world of evil and brokenness, where you can no longer see Hashem. The mateh represents a straight path, through which you trace yourself back to your source.

When Moshe first encounters Hashem, he is told to thrust the mateh to the ground, where it then transforms into a snake. When something is thrust to the ground, low and distant from its transcendent source, it becomes bent and evil. But when Moshe lifted it up, toward the sky, tracing it back to its source, straightening the bent path, it became a mateh, a source of good.

Explaining Moshe’s Showdown with Pharaoh

With this deep understanding of the bent and straight path, we can understand Moshe and Aharon’s showdown with Pharaoh in a new light. The Midrash explains that when Moshe and Aharon turned their mateh into a snake in front of Pharaoh, he laughed. Not only did he proceed to do the same thing himself, but he then brought his magicians, and even his wife, to do the same, as well. To drive his point home, he proceeded to bring the schoolchildren in to perform this trick, as well. Laughing at Moshe, he exclaims: “One who has goods to sell should take them to a market that is short on supply. You’ve brought your goods to an overstocked market.” In other words, we are not impressed. Moshe responds, “One who has top-quality produce takes it to a well-stocked market, where the dealers are experts and will recognize the superior quality of the goods.” On that note, Aharon’s mateh swallows all the other snakes, once it has already transformed back into a mateh.

The deep explanation behind this cryptic scene is not just that Moshe overcame Pharaoh and Mitzrayim. Remember, the Midrash explained that the snake and Mitzrayim represent the bent path; the mateh represents the straight path. It doesn’t say that Moshe and Aharon’s snake swallowed Pharaoh’s snakes, it says that Moshe and Aharon’s mateh swallowed Pharaoh’s snakes! This mean that the straight path overcame the bent path; good overcame evil.

Straightening the Bent Path

Everything in our world is potential, having the ability to be used for good or for evil. The choice is ours. Just as in the introductory story, we get to choose which of the two wolves to feed, we also get to choose how to use the potential in this world. The pull and temptation of negative desire can be overwhelming, but the pursuit of truth, of the straight path, must prevail. We each get to choose who we will become.

Let us be inspired to straighten the bent path, build clarity from confusion, oneness from brokenness, and bring the world to its ultimate destination.

Rabbi Shmuel Reichman is the author of the bestselling book, The Journey to Your Ultimate Self, which serves as an inspiring gateway into deeper Jewish thought. He is an international speaker, educator, and the CEO of Self-Mastery Academy. After obtaining his BA from Yeshiva University, he received s’micha from RIETS, a master’s degree in education, a master’s degree in Jewish Thought, and then spent a year studying at Harvard. He is currently pursuing a PhD at UChicago. To invite Rabbi Reichman to speak in your community or to enjoy more of his deep and inspiring content, visit his website: www.ShmuelReichman.com.