“You shall not hate your brother in your heart; you shall reprove your fellow and do not bear a sin because of him.”

– VaYikra 19:17

Why Should I Be Punished for Your Sin?

When the Torah mentions the obligation to rebuke a fellow Jew, it ends with the words, “and do not carry a sin because of him.” The Targum translates this as, “and do not receive a punishment for his sin.”

According to the Targum, it appears that if Reuven ate a ham sandwich and I didn’t rebuke him, I would be punished for his sin. This seems difficult to understand. Why should I be punished for his sin? At most, you might argue that if I was capable of rebuking him and didn’t, I would be responsible for the sin of not rebuking him. But how do I become responsible for the sin that he perpetrated? He transgressed it; I didn’t.

One Nation, One People

The answer to this question is based on understanding the connection that one Jew has to another.

The Kli Yakar brings a mashal. Imagine a man who is on an ocean voyage. One morning, he hears a strange rattling sound coming from the cabin next to his. As the noise continues, he becomes more and more curious, until finally, he knocks on his neighbor’s door. When the door opens, he sees that his neighbor is drilling a hole in the side of the boat.

“What are you doing?” the man cries.

“Oh, I’m just drilling,” the neighbor answers simply.

“Drilling?”

“Yes. I’m drilling a hole in my side of the boat.”

“Stop that!” the man says.

“But why?” asks the neighbor. “This is my cabin. I paid for it, and I can do what I want here.”

“No, you can’t! If you cut a hole in your side, the entire boat will go down.”

The nimshal is that the Jewish People is one entity. For a Jew to say, “What I do is my business and it doesn’t affect anyone else” is categorically false. My actions affect you, and your actions affect me – we are one unit. It is as if I have co-signed on your loan. If you default on your payments, the bank will come after me. I didn’t borrow the money – but I am responsible. So, too, when we accepted the Torah together on Har Sinai, we became one unit, functioning as one people. If you default on your obligations, they come to me and demand payment. We are teammates, and I am responsible for your performance.

The Targum is teaching us the extent of that connection. What Reuven does, directly affects me – not because I am nosy or a busybody, but because we are one entity, so much so that I am liable for what he does. If he sins and I could have prevented it, that comes back to me. A member of my team transgressed, and I could have stopped it from happening. If I did all that I could have to help him grow and shield him from falling, I have met my obligation and will not be punished. If, however, I could have been more concerned for his betterment and more involved in helping to protect him from harm and didn’t, then I am held accountable for his sin.

Don’t Rebuke Others – It Doesn’t Work

This perspective is central to understanding why rebuke doesn’t work.

When Reuven goes over to Shimon and “gives it to him good,” really just showing what he did wrong, the only thing accomplished is that now Shimon hates Reuven.

To properly fulfill the mitzvah of tochachah, there are two absolute requirements. The first is in regards to attitude, and the second relates to method.

What Is My Intention?

When I go over to my friend to chastise him, the first question I must ask myself is, “What is my intention?”

If my intention is to set him straight and stop him from doing a terrible sin, then I will almost certainly fail. The only intention that fits the role of a successful mochiach is: “This is my friend; I am concerned for his good.”

If I am looking out for k’vod Shamayim, or if I am a do-gooder concerned for the betterment of the world, then my words will accomplish the exact opposite of their intended purpose. I won’t succeed in separating my friend from the sin; I will only succeed in separating him from me. The first requirement for the proper fulfillment of tochachah is that it must be out of love and concern for my friend.

The second condition for tochachah to be effective has to do with the way it is delivered.

Do You Shout When You Put on T’filin?

The Chofetz Chaim was once approached by a certain community leader who complained that no matter how much he reproached the people of his town, they didn’t listen. The Chofetz Chaim asked this person to describe how he went about rebuking his townspeople. The man described his method of yelling fiery words at them. The Chofetz Chaim asked him, “Tell me, when you put on t’filin, do you shout and carry on? Why do you feel the obligation to do so when you do this mitzvah?”

One of the most basic concepts of human relations is that people hate criticism. We hate it worse than poison, and we avoid it like the plague. When you criticize me, I become hypersensitive. If you whisper, I hear it as loud speech, and when you speak quietly, I hear it as if you are shouting in my ears. Being aware of this is vital in choosing the method, tone, and words with which I approach my friend. The mitzvah of tochachah is to help my friend improve. Without a strategy that is sensitive to human nature, even the best of intentions will backfire. To succeed in this mitzvah, I need to choose my words very carefully, making sure that they are as soft and non-offensive possible. This is the second requirement of the mitzvah.

Out of Concern and Love

The reality is that this is a very difficult mitzvah to perform correctly. Typically, we find ourselves either not wanting to get involved or saying things that cause more harm than good. But when the driving force in doing this mitzvah is concern for the good of our friends, and we carefully study human nature and choose our words guardedly, Hashem will help us to perform it properly.

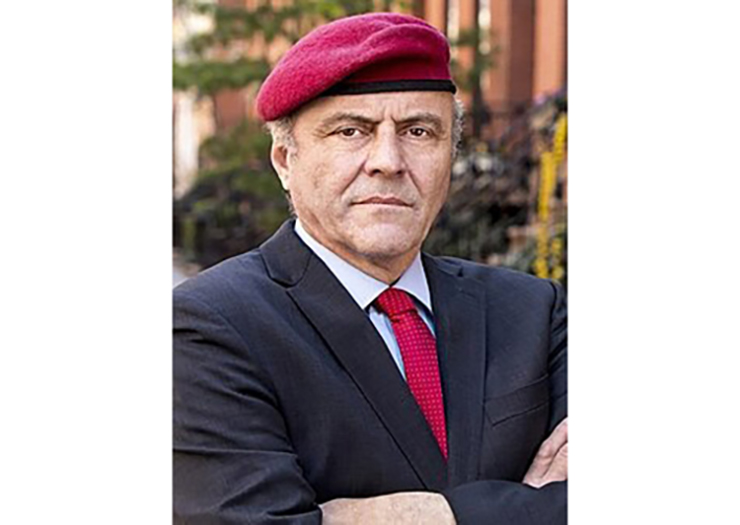

Born and bred in Kew Gardens Hills, R’ Ben Tzion Shafier joined the Choftez Chaim Yeshiva after high school. Shortly thereafter he got married and moved with his new family to Rochester, where he remained in for 12 years. R’ Shafier then moved to Monsey, NY, where he was a Rebbe in the new Chofetz Chaim branch there for three years. Upon the Rosh Yeshiva’s request, he stopped teaching to devote his time to running Tiferes Bnei Torah. R” Shafier, a happily married father of six children, currently resides in Monsey.