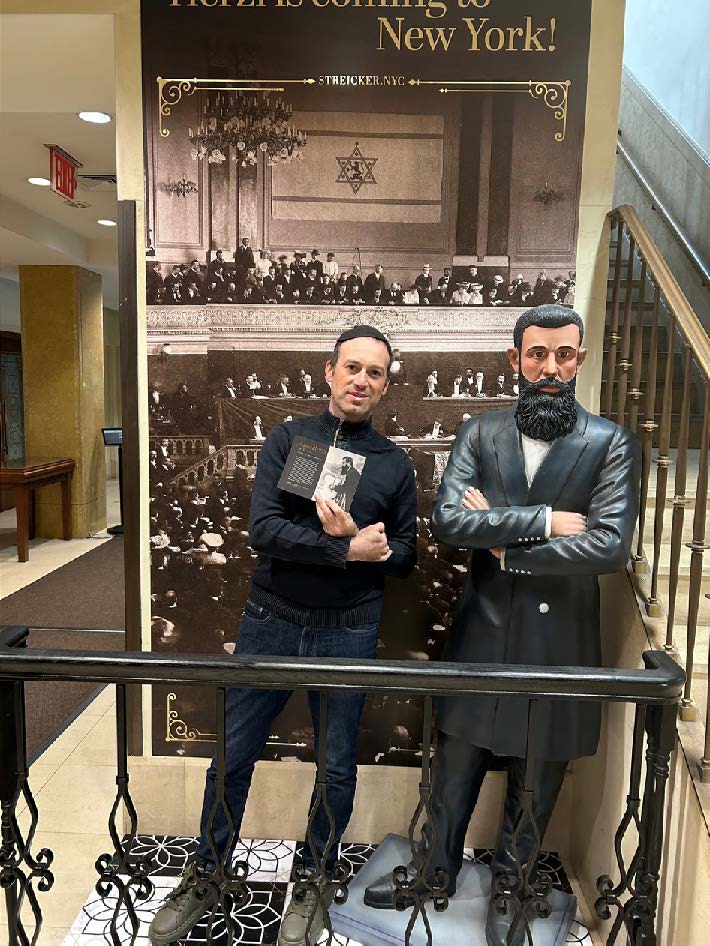

The best-known photo of Theodor Herzl shows him learning on a hotel balcony in Basel, where he organized the First Zionist Congress in 1897. That shot became part of Jewish popular culture, appearing in mosaics, puzzles, carpets, and a flag flying on the side entrance at Temple Emanu-El on the Upper East Side. The flag serves as an introduction to All About Herzl, an exhibit on his lasting image and impact at the temple’s Bernard Museum.

In the city that has a Jewish museum uptown and another downtown, the flagship temple of American Reform Judaism has its own museum that feels intimate, where a visitor can contemplate the displays without distraction. Born to an affluent family in Budapest, Herzl and his wife Julie were expected to live comfortable and assimilated lives, with his education as a lawyer and career writing essays and newspaper articles. The conviction of Alfred Dreyfus in 1894 and anti-Semitic reactions that followed changed his life. He became a full-time activist fighting for Jewish self-determination.

“Let me repeat once more my opening words: The Jews who wish for a State will have it. We shall live at last as free men on our own soil and die peacefully in our own homes. The world will be freed by our liberty, enriched by our wealth, magnified by our greatness,” he wrote in his book Judenstaat, which was published two years after the Dreyfus Trial.

At the exhibit, Herzl’s life begins with a handsome childhood photo and a report card saved by his mother. Fast forward to 1897 and the First Zionist Congress, which looks like a graduation class portrait with the leading faces of the movement: Max Nordau, Menachem Ussishkin, and Achad Ha’am. They also became Zionists after encountering anti-Semitism. Most of the artifacts come from the collection of Toronto lawyer David Matlow, an admirer of Herzl.

The exhibit’s organizers and hosts note that the founding mission of Zionism is misunderstood in today’s political climate and, having died at a young age, Herzl has been claimed by liberals and nationalists within Zionism as their own. Between the First Zionist Congress and his death in 1904, Herzl struggled to gain the support of prominent Jews. A handwritten reply from Baron Edmond James de Rothschild was polite but dismissed political Zionism as unrealistic.

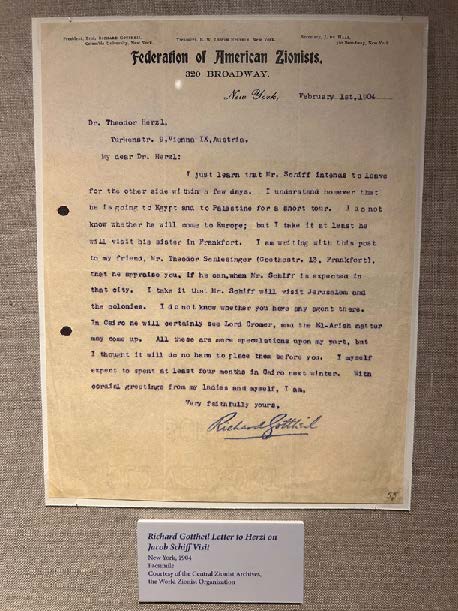

Another letter on display was written by Richard Gottheil, a member of Temple Emanu-El and an early believer in the cause. His letter tipped off Herzl about fellow congregant Jacob Schiff’s planned visit to Palestine as an opportunity to meet the American Jewish philanthropist and convince him of Zionism. Then there is the vote tally on the controversial Uganda proposal, which caused Herzl plenty of anguish. Should Zionists continue to demand Palestine despite opposition from the Turkish sultan, the pope, and noncommittal European leaders, or accept a distant African land as an alternative? Gottheil’s letter was dated February 1, 1904, and he died five months later at 44.

Not trusting Julie, Herzl requested that his mother raise their three children, but she was also not fit for the task and had governesses watching over them. Their lives were short, with Paulina (Tirzah) suffering from mental illness and drug abuse. When she died of a heroin overdose, her distraught brother Hans (Shimon) killed himself. The youngest child, Trude (Frumah) was institutionalized for many years and was killed in Theresienstadt.

At the same time, Herzl’s likeness, the prophetic image of a bearded man gazing from the balcony in Basel, became the defining portrait of his movement. He intended the World Zionist Congress to be a diverse body representing Jews from all corners of the world, spanning the religious and political spectrums. As the movement fragmented between Labor Zionists and Revisionists, secularists and religious Zionists, they all speak with reverence about Herzl.

In this regard, he can be compared to another national father, George Washington, the only president who did not belong to a political party, and who died two years after retiring from office. Both major American parties quote him and depict themselves as his heirs. In a deeply polarized society, people long for the leadership of a unifying founder. In posterity, this is the role that Herzl continues to play 120 years after his passing.

Produced in partnership with the World Zionist Organization, “All About Herzl: The Exhibition” is on display at Temple Emanu-El’s Streicker Cultural Center through January 23, 2025.

By Sergey Kadinsky