Astronauts really are made of the right stuff. They are exceptionally bright, have complex technical skills, are in outstanding physical condition, and have perfect vision. They are also exceptionally courageous, reliable in case of an emergency, and trusted with highly prized secrets. Their missions into space helped transform the present into a better tomorrow. Many, interestingly enough, are Jewish.

Mission Almost Impossible

A ride on a spaceship may look like a lot of fun, but it’s also a whole lot more than that. Astronauts agree that the feeling of a rocket lifting off is exhilarating. Peggy Whitson, who has flown on three missions for NASA, describes it this way: “Six seconds before the launch, the main engines ignite and the vehicle is doing a tilt action. When it comes back to straight up, that’s when the solid rocket boosters ignite. You are pushed back in your seat, you feel the G-forces and the acceleration immediately, and the vibration is pretty intense.”

Return to Earth is also no piece of cake. Often it causes dizziness and nausea, and right before reentering Earth’s atmosphere there is a feeling of free-fall – not a very pleasant experience. Lift-off and landing are the most dangerous times of a mission.

Flying the Flag

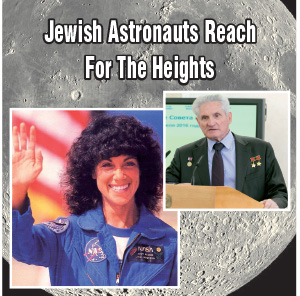

Most Jewish astronauts flew with an American flag on their spacesuits – but not all did. In fact, the first Jew in space was a Soviet cosmonaut.

Boris Volynov earned a degree as a pilot-engineer-cosmonaut; but in the Soviet Union in the 1960s, being Jew hindered selection on a mission into space. Apparently, luck also is a factor.

Volynov trained as one of two possible commanders for the Voskhod 1 mission in 1964, but he and his fellow crew members were bumped just three days before their scheduled launch date.

Volynov spent another year training for another mission, the Voskhod 3, but his luck was no better on that one. Just ten days before launch, this mission was scrubbed.

But in January 1969, he finally got his big break. The Soyuz 5 was supposed to rendezvous and dock with the Soyuz 4 in space; then these vehicles were supposed to separate, and Volynov was prepared for a solo re-entry to Earth.

Because of technical problems, however, the vehicles began to tumble. When Volynov regained control of the ship, the danger had still not passed. Following re-entry, the parachutes deployed only partially, causing a hard landing, which broke some of Volynov’s teeth.

Volynov had an even more harrowing experience aboard a subsequent mission, the Soyuz 21. A crew member became ill and Soviet mission control decided to bring the cosmonauts back as soon as possible. A series of equipment failures made that impossible and the craft was out of range of ground communications. This emergency lasted for an entire orbit – 90 minutes – until the spacecraft finally responded to commands. When the vehicle was returning, it made a scary, hard landing.

In the years since, Volynov’s career has been more tranquil; he received numerous honors, awards, and even had his likeness appear on a postage stamp.

“Never Played Anything Softly”

Pianist turned astronaut Judith Resnik was born in Akron, Ohio. According to Wikipedia, she was raised in an observant Jewish home in a family of rabbinical descent, studied at Hebrew school every weekend, and celebrated her bas mitzvah. She was only the second American woman to go into space and the first Jewish woman of any nationality.

When still a child, she was recognized for her “intellectual brilliance”; and in elementary school, classmates nicknamed her “The Brain.”

In her youth, Resnik was accepted by Juilliard and planned on a career as a concert pianist. However, after receiving a perfect score on her SAT exam – at the time, one of only 16 girls in US history to do so – she was persuaded to shift gears, and careers.

Resnik turned down her place at Juilliard to study at Carnegie Mellon, where she earned a degree in electrical engineering. Subsequently, she earned a PhD with honors in that field at the University of Maryland.

Resnik made good use of her talents, becoming an electrical engineer, a software engineer, a biomedical engineer, a pilot, a gourmet cook, and a classical pianist who could play “with more than technical mastery.” Questioned about her intensity, she replied that she “never played anything softly.”

As a Mission Specialist on the first voyage of Discovery, Resnik was in charge of the shuttle’s robotic arm, which she helped create and at which she was an expert. She also was a Mission Specialist on the Challenger in 1986.

Before that flight, Resnik consulted a rabbi about lighting Shabbos candles Friday night. Since lighting a fire on a spaceship was not possible, she did the next best thing: lighting electric lights at the time of the onset of Shabbos at her hometown of Houston.

The Challenger exploded 73 seconds after it was launched when an O-ring seal in the right solid rocket booster failed; all seven crew members were killed. Resnik earned high marks from her fellow astronauts, and her passing, along with those of the rest of the crew, deeply saddened Americans.

Israel’s First Man in Space

Ilan Ramon was born in Ramat Gan, Israel. His father fled from the unfolding nightmare in Germany in 1935, but his mother and grandmother were taken prisoners in Auschwitz. Ramon became a pilot in the IAF in 1974 and accumulated thousands of hours of flying experience. He became adept at flying a variety of fighter planes used by the IAF, including the Mirage III, the Phantom, and the F-4 and F-16. He was so skilled a pilot that he was selected for Operation Opera, Israel’s top-secret mission that destroyed Iraq’s Osirak reactor – the youngest pilot on that mission.

In July 1998, Ramon began training as a Payload Specialist for the Space Shuttle Columbia. At the same time, he made a point of speaking to Holocaust survivors. “They look at you as a dream that they could have never dreamed of,” he said. The Columbia lifted off on January 18, 2003.

Ramon saw his mission in a broad perspective. “I feel I am representing all Jews and all Israelis,” he said. He requested kosher food for the flight, and asked a rabbi for guidance about observing Shabbos, since a day in space is only 90 minutes. And on Friday night, when his craft flew over Jerusalem, he recited Kiddush, sanctifying the Sabbath.

Ramon also carried other very precious items into space, among them: a pencil sketch of how the Earth looks from the Moon made by 14-year-old Petr Ginz (who died in Auschwitz), a miniature Torah that survived the Holocaust, and a barbed-wire mezuzah as a symbol of the Holocaust.

In a tragic accident, 15 days later the Columbia exploded, just 16 minutes before its scheduled landing. The entire crew perished.

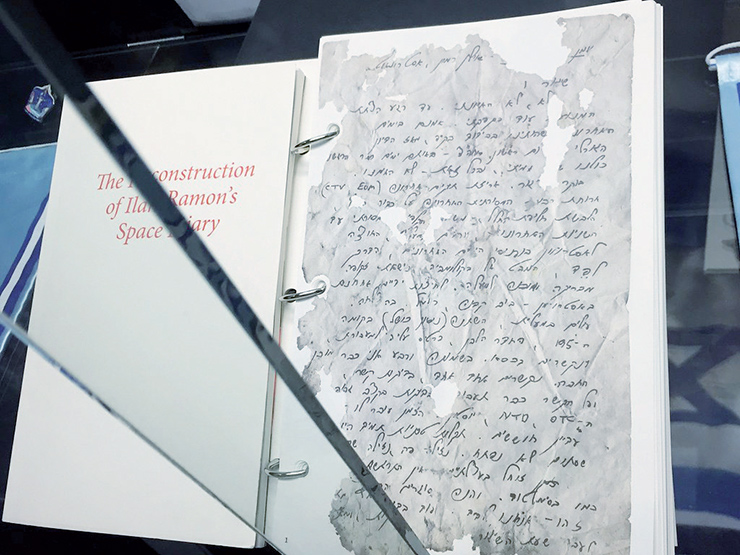

While in space, he kept a diary about his flight. Thirty-seven pages miraculously survived the extreme heat of the explosion, extreme atmospheric cold, and microorganisms that covered the pages in the months after they fell back to Earth. “There is no rational explanation for how it was recovered when most of the shuttle was not,” the curator of the Israel Museum said. Ramon is the only foreigner who ever received the United States Congressional Space Medal of Honor.

Showing Their Jewishness

There have been other Jewish astronauts, too. Among them:

- Jeffrey Hoffman was the first Jewish American man in space and the first person to ever bring a Torah into space; it was wrapped in his grandfather’s talis katan. During his 1996 mission on the Space Shuttle Columbia, he read verses in Hebrew from B’reishis as the spacecraft passed over Jerusalem. Hoffman also took four mezuzos with him on the Discovery 2 mission.

- David Wolf was in orbit during Chanukah. Much like Resnik, he wanted to light candles on a menorah, but he, too, was not able to light a fire. However, there were no restrictions on spinning a dreidel and he did. In the zero gravity of the space capsule, he said he “probably made a record dreidel spin; it went for about an hour and a half until I lost it.” The dreidel showed up a few weeks later in an air filter. “I figure it went about 25,000 miles,” he said.

Wolf described his first spacewalk as a religious experience. He and fellow Jewish crew member Martin Fettman also took a shofar and some mezuzos into space. Wolf fasted on Yom Kippur, although he wasn’t sure when to do so because the spaceship orbited Earth every 90 minutes.

- In 2008, Gregory Chamitoff took mezuzos shaped like rockets on the International Space Station and placed them on the door post near his bunk bed.

- Gary (Garrett) Reisman was the first Jewish astronaut to live on the International Space Station. Reisman flew right before Pesach and asked for permission to bring matzah aboard with him. Mission control thought the crumbs could pose a problem and his request was reluctantly turned down.

Other Jewish astronauts include Mark “Roman” Polansky, Scott “Doc” Horowitz, John Grunsfeld, Jerome “Jay” Apt, Marsha Sue Ivins, and Ellen Louise Shulman Baker.

One other name should be added to this list of Jewish astronauts – that of Yuri Gagarin – maybe. Gagarin received international fame when in 1961 he became the first human to travel into space. Gagarin claimed to be a devout Christian. In 1968, he died when the MIG-15 jet he was piloting crashed, and that touched off the controversy about his religion. The following day, a relative, who was a professor at a US university, said that Gagarin was Jewish but kept that fact secret so his career would not be hindered. The cause of the crash of Gagarin’s jet has been subject to a great many conspiracy theories. If Gagarin was really Jewish, he took that secret to his grave.

That so many of America’s astronauts are Jewish should be a source of pride to all of us. It should also elicit appreciation to our government for allowing and even helping astronauts practice their religion. After all, not all governments are that considerate.

Sources: airspacemag.com; aish.com; aaas.org; britannica.com; forbes.com; inc.com; israelstamps.com; jewcy.com; space.com; wikipedia.com

By Gerald Harris