A Pulitzer Prize-winning graphic novel of Holocaust survival was banned by a county school board in Tennessee last month on the excuse that its content is inappropriate for young audiences.

“There is some rough, objectionable language in this book, and knowing that and hearing from many of you and discussing it, two or three of you came by my office to discuss that,” said McMinn County Director of Schools Mr. Lee Parkison. “We decided the best way to fix or handle the language in this book was to redact it.”

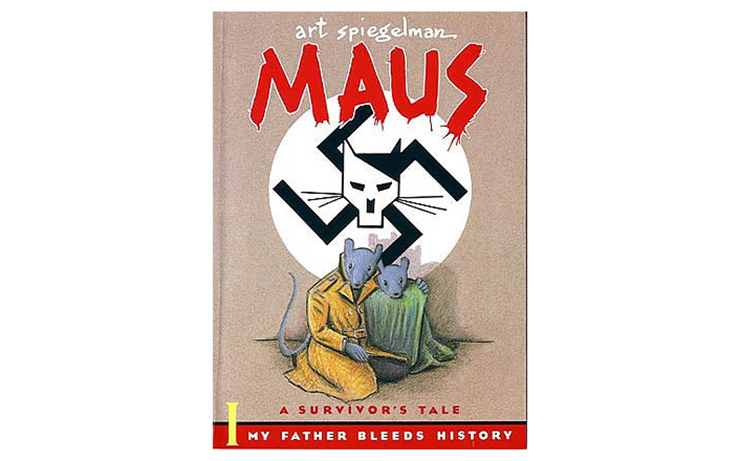

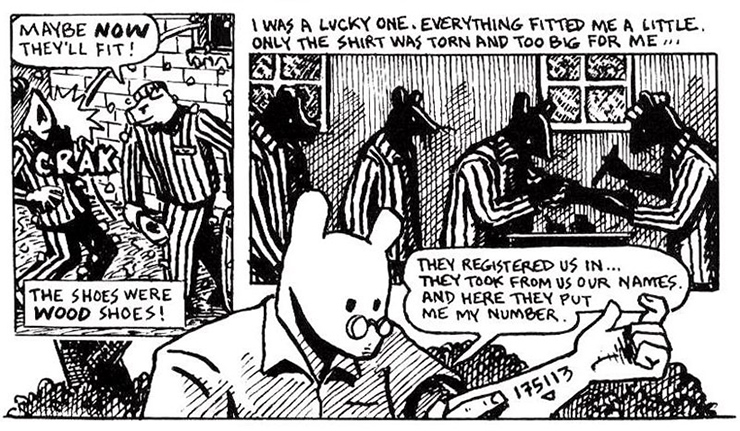

The controversial book is Maus, a cartoon account of the author interviewing his father Vladek about his surviving the Holocaust. Prior to that school board meeting in Tennessee on Monday, January 10, Maus was part of the eighth-grade curriculum in McMinn County’s public schools. The book’s use of vulgar language, and depictions of nudity, murder, and suicide, led the school board to pull it from classrooms.

“I think any time you are teaching something from history, people did hang from trees, people did commit suicide, and people were killed, over six million were murdered. I think the author is portraying that because it is a true story about his father who lived through that,” supervisor Melasawn Knight said at the meeting. “He is trying to portray that the best he can with the language that he chooses that would relate to that time, maybe to help people who haven’t been in that aspect in time to actually relate to the horrors of it.”

The removal of the book became a national story in context with the politics of McMinn County – deeply conservative – where there is also opposition towards teaching “critical race theory,” and other history lessons that describe unpleasant events in terms of the injustices committed, and connecting them to contemporary situations relating to race, ethnicity, and economic class. It has also become a big story as it tackles the question on appropriateness based on age.

“You can certainly teach the Holocaust in many ways without emphasizing blood, in an age-appropriate level, even from kindergarten,” said Rabbi Moshe Rosenberg, a fifth-grade teacher at the SAR school in Riverdale. He is also the author of the Harry Potter Haggadah. “Our school has grade-appropriate programs. My father escaped on a Sugihara visa.”

At the same time, Rabbi Rosenberg recognizes why there were complaints about the book, and he recalled how Jewish readers felt about Maus when it was published between 1980 and 1991.

“You’ve got mice that are undressed, perish the thought. That’s what upset the school board. A lot of Jews were uncomfortable with alternative ways of telling the story. We’ve gone way beyond that at this point. Life is Beautiful turned it into a game with an emotional wallop. You have to be creative in certain ways.”

Spiegelman’s depictions may not be appropriate for a yeshivah audience, but in public schools the average eighth-grader is aware of vulgar language and violence from popular culture. “No reason not to use that in eighth grade,” Rabbi Rosenberg said. “The graphic novels that kids read. They’ve seen Hunger Games. We’ve gone beyond that.”

At Yeshiva Har Torah the approach towards holocaust education is based on age, starting with broad topics which become specific as the student grows older. “We start with artifacts and heirlooms. Only in the fifth grade do we discuss the Holocaust, but none of the trauma,” said Rosh HaYeshiva Rabbi Gary Menchel. “In middle school we study cities in Europe as they were before the Holocaust. Finally in eighth grade, students can volunteer for Names Not Numbers, a project where they interview survivors and we prepare them for it.”

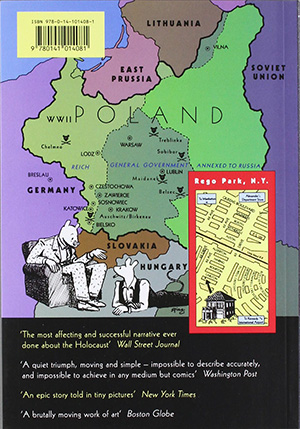

My first exposure to Maus was during middle school, on a visit to the Rego Park library near my childhood home. I was excited to see a map of the neighborhood on the back cover, and the cartoonish appearance of Jews as helpless mice suffering under the merciless German cats. Each time I read this book, I understood in it more detail and the choices that Spiegelman made in this book. Cartoons are relatable to young audiences, but the depiction of humans as separate species is a very mature and thoughtful way to express the intentions of the Nazis.

When I was exposed to the political novel Animal Farm by George Orwell, I understood the value of depicting Jews, Germans, and Poles as different animals. In the nature, each has its place on the food chain and that is how Nazi ideology regarded non-German ethnicities and races.

Rabbi Rosenberg added that the choice to depict Jews as mice is a factual example of Nazi policy. “Jews were described as vermin. They were dehumanized. Vermin are not murdered. They are exterminated.”

Spiegelman is not a religious Jew, and his resume includes work for adult magazines, but in his choice to depict people as animals, he tapped into a popular Jewish method of storytelling, the use of allegory. “Jewish tradition has a long history of m’shalim. Sefer Shoftim, perek tes, is an example. Uncomfortable information is conveyed in a mashal,” Rabbi Rosenberg said.

In his interview with MSNBC host Joy Ann Reid, Spiegelman described the McMinn County school board as “stupid.” He noted two examples from the book, an illustration of his mother’s suicide and him cursing at his father for burning his mother’s journal, which told the account of her survival. In a separate interview with CNN, Spiegelman described the school board’s unanimous decision as “Orwellian.”

“The book puts memories in order, and that’s what comics do. It was about learning how to get inside somebody else’s head, it’s not about being programmed,” Spiegelman told Reid. “In a time when there was never such a thing as graphic novels.”

By Sergey Kadinsky