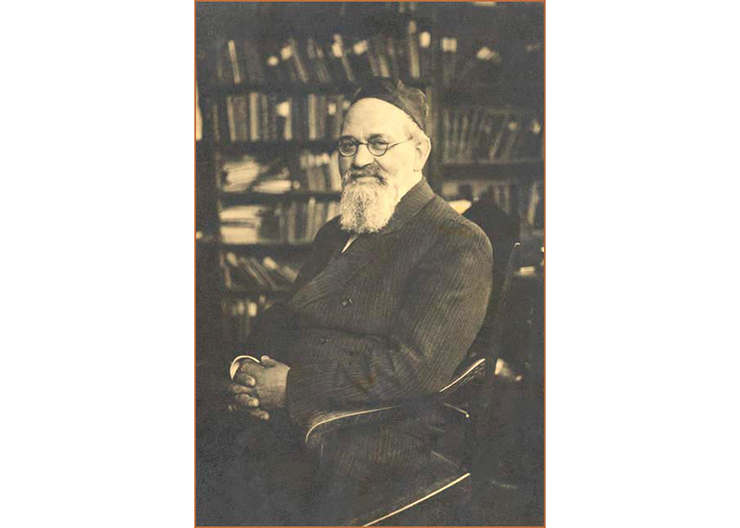

On the Saturday night before Rosh HaShanah in 1917, the words of one German rabbi, Joseph Carlebach, evoked a powerful message.

In 1915, sixteen German rabbis were sent by the German army high command to the Eastern front to administer to the needs of Jewry under German occupation in the Eastern Zone. These lands included Lithuania and Poland. This was a daunting task, as Jewish masses suffered from pogroms, expulsions, starvation, and disease.

These rabbis were also entrusted with an additional task.

The German occupation forces deemed it important to provide an education for Jewish children that included secular subjects. One of the rabbis, Joseph Carlebach, was delegated the task of organizing an educational system for Jews under German occupation in the Lithuanian city of Kovno. The rabbi devised a program based upon the German model of Torah Im Derech Eretz, “Torah Education with Ways of the Land,” (integrated subjects) as he consulted with local rabbinical leaders. The relatively small school soon grew as parents put their trust in Rabbi Carlebach. The rabbi was also responsible for the reopening of the great Slobodka Yeshiva, which was closed due to the ravages of the war.

On that Saturday night, Selichot services, September 15, 1917, Rabbi Carlebach spoke at the synagogue, Ohel Yaakov, in Kovno. Jews assembled there to hear the words from the esteemed scholar and leader. The German commanders insisted that the German-Jewish soldiers sit on one side of the synagogue, Russian Jewish prisoners of war on the other, and in between them, the local Jews.

That night, Rabbi Carlebach stunned the audience, which expected to hear words in support of his native Germany. He began with the common phrase in German circles, “We did not want this war,” implying that Germany’s enemies, the Entente, drew her reluctantly into the conflict. But the rabbi’s message was far different. He was actually implying that no one in that room wanted this destructive and devastating war. Rabbi Carlebach did not absolve Germany from its responsibility for the war and its resulting carnage.

The rabbi also praised the level of Torah study in the Eastern territories and stated that German Jews had much to learn from the Eastern Jewry. He mentioned how German Jewish soldiers were learning Torah from local Jews. He also stated that it was symptomatic that Jews from different sides sat together in synagogue, separated by a German ruling, prohibited from mingling.

That night they sat together as one entity. They were not enemies on opposing sides or superiors; they were not victors and prisoners. They were indeed brothers commiserating over the immense tragedy of that war, praying to the same Father in Heaven. Amid the horrors, there was some light.

Rabbi Carlebach’s words were reported to the authorities, who had the rabbi sent to the front lines for a month as a punishment. There must have been at least one irate German soldier present who reported the event. If not for the intervention of friends, the punishment would probably have been far worse.

During those moments of reflection as Rosh HaShanah was approaching, the rabbi spoke directly to the audience expressing regret. Germany, whose leaders had professed equality for all its citizens regardless of religion and ethnic background when the war began in 1914, was already turning its back upon its Jews. By 1916, the failures and losses incurred were already being blamed upon the Jews, who were being accused in the press and by some politicians of disloyalty, despite their zealous support and sacrifices on behalf of the war effort.

Russian Jewry was also faced betrayal. About 600,000 Jews had fought valiantly for the Czar while at the same time some Russian and aligned Cossack forces were committing heinous crimes against Jewish civilians on both the Russian and Austrian fronts.

Together, Jews on opposing sides could reflect upon the events of the day and call out to their Heavenly Father as one beseeching His mercy upon Jewry and mankind.

That Selichot night was a moment of reckoning, where Rabbi Carlebach’s messages resonated.

Parts of this article were from “Voices of Opposition to the First World War Among Jewish Thinkers” by Rivka Horowitz. Leo Baeck Institute vol XXXIII, 1988.

Larry Domnitch is the author of The Impact of World War I on the Jewish People, (Second Edition), by Urim Publications. He lives in Efrat