An overlooked Jewish community with a long and unique history is the subject of a virtual photo exhibition sponsored by Queens College. This past Thursday, the school hosted a Zoom conversation involving Greek-American activists and members of the Romaniote Jewish community in a discussion on “Romaniote Memories, a Jewish Journey from Ioannina, Greece, to Manhattan: Photographs by Vincent Giordano.”

“Vincent Giordano was neither Jewish nor Greek. He stumbled upon Kehilla Kedosha Janina in 1999. In 2006 he traveled to their ancestral home in Greece for the High Holidays,” said Queens College President Frank Wu. “He devoted the last decade of his life to this community. It’s multiculturalism at its best.”

Ioannina is a city in northwestern Greece whose Jewish history began shortly after the Churban Bayis Sheini (Destruction of the Second Temple), when the Romans destroyed Jerusalem, triggering the dispersal of Jews across their empire. One group settled in Greece and developed its own Judeo-Greek dialect, piyutim, machzor, and wedding customs. “The Romaniote community is the oldest Jewish community in Europe,” said Greek Ambassador to the US Alexandra Papadopoulou. “The conversation focuses mostly on Thessaloniki and I’m proud that we’re focusing on the Romaniote community.”

Papadopoulou was referring to the city known in Jewish history as Salonika, where an influential Sephardic population lived until the Holocaust. They arrived in Greece following the inquisition in Spain, and quickly outnumbered the older Romaniote community in this country. “The Sephardim came at the invitation of the sultans. They were richer, more powerful, and more politically connected,” said Samuel Gruber, president of the International Survey of Jewish Monuments. “They superseded the Romaniote communities.” Both communities lost most of their members in the Holocaust, with most survivors immigrating to Israel and America.

Giordano died in 2010, and his widow Hilda donated his photographs of the Romaniote community to the Hellenic American Project at Queens College, headed by Professor Nicholas Alexiou. In partnership with the Queens College library, an exhibit was planned for this year, but the global pandemic forced it to go online. With support from the International Survey of Jewish Monuments, a website was created to show some of Giordano’s work that documented America’s only Romaniote synagogue, Kehilla Kedosha Janina on Manhattan’s Lower East Side; and the synagogue in Ioannina, with images of celebrations and prayers on both sides of the ocean. Giving the Zoom meeting an authentic look, Gruber used Giordano’s photo of the synagogue in Ioannina as his background.

The virtual exhibit included congratulatory messages from Professor Arnold Franklin, Jewish Studies Department Chair, Archbishop Elpidophoros of the Greek Orthodox Archdiocese of America, and the Greek Embassy in Washington, among other organizations.

“Beautiful things don’t ask for attention. Sometimes they hide in the shadows. This is the story of the Jewish community,” said Greek Consul General in New York Konstantinos Koutras. “It is a distinct culture with a dialect, prayer books, and food.”

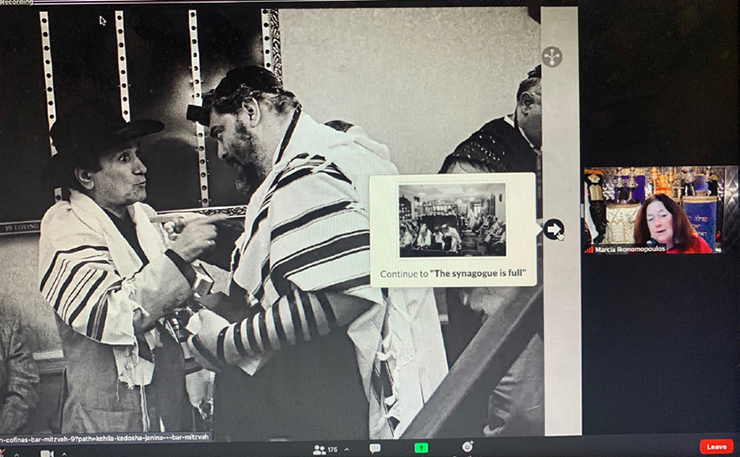

In one photo, two members appear to be staring each other down and pointing fingers at the Romaniote synagogue in Manhattan “This is not an argument, it’s a conversation,” said Marcia Ikonomopoulos, director of the museum at Kehila Kedosha Janina. “Before COVID-19, services on a regular day were very important.”

Besides the museum, the synagogue has hosted an outdoor fair since 2014 on its Broome Street block that brought Jews and Greek-Americans together in a celebration of their shared culture. In the photo exhibit, Giordano documented the bar mitzvah of Seth Cofinas in 2007. The unique aspects of Giordano’s work are the grainy black and white appearance of his subjects, giving them a timeless quality in a synagogue that has not changed anything in its rituals since opening nearly a century ago. Each photo has a detailed explanation so that any viewer can understand this community, its people, and their rituals.

Woodmere resident Asher Matathias, whose father was born in Greece, spoke of the struggle to pass on history and minhagim. “We are assimilating, intermarrying perhaps. It is a challenge to maintain our identity,” he said.

Perhaps it is inevitable for the children of olim and immigrants to blend into the larger American Jewish community, or the Israeli Jewish population. In this intra-Jewish “assimilation,” the cultural differences between Hungarian and Polish Jews are blurred as they are absorbed into the larger Ashkenazi identity, and likewise for Jews of Middle Eastern and North African ancestry, who are associated with Sefardi Jewry. Descendants of Romaniote Jews argue that their community is neither Ashkenazi nor Sefardi.

Their ancestral hometown, Ioannina, today has fewer than 50 Jewish residents. In 2019, Moses Elisaf was elected as its mayor, the first Jewish mayor in any Greek city and a source of pride to Romaniote Jews worldwide. He also extended his congratulations to Queens College on its virtual photo exhibit.

In total, over a hundred photographs are featured in this exhibit, divided by topic. “I wondered how a community and its culture wither away and vanish – which forces are at work, and which are not? I began to photograph and document the synagogue and the community,” Giordano said in a statement in 2007. “This effort was transformed into an incredible personal journey of discovery, filled with wonderful people, interesting experiences, and fascinating places.”

The online exhibit can be seen here: www.scalar.usc.edu/works/romaniote-memories/index.

By Sergey Kadinsky