When my family immigrated to New York, we experienced elements of Jewish American culture that were fading from the scene. We vacationed at The Pines Resort in the Catskills shortly before its closing, and having spent many of my after-school hours at the public library, I fell in love with the quick one-liners of the comedians who performed at The Pines in its heyday.

Their illustrated counterpart was the Usual Gang of Idiots, the cartoonists of Mad Magazine, who parodied the politics, films, and events of their time in black and white with hints of their Jewish heritage in their characters and word bubbles. Last week, the last of this gang, Al Jaffee, died at 102.

“Is it raining?” a wife asks her husband as he comes home in a coat soaked in water. “No, I always shower with my clothes on before I come into the house,” he replies in one of Jaffee’s Snappy Answers to Stupid Questions. In this Mad Magazine feature, there are always three answers provided, with a fourth thought bubble containing dotted lines, in which Jaffee gave readers the opportunity to contribute their own smart-aleck reply.

“The main thing about Mad is that it’s not a preachy magazine,” Jaffee said in a 2016 interview with The Guardian. “It’s not selling one kind of politics or one kind of religion or sports team or anything like that.” At the time, he was 95, the recipient of a Guinness World Record for the longest-working cartoonist.

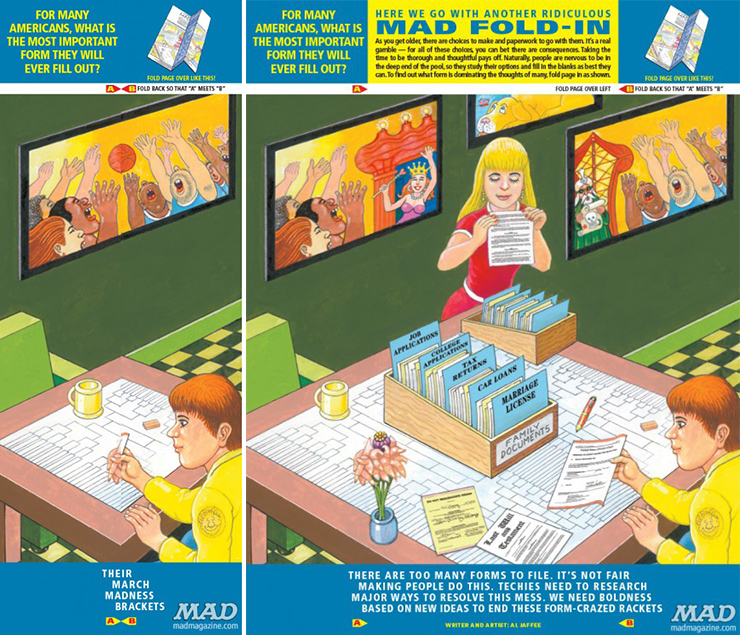

In that interview, much of the attention was given to his Mad Fold-In feature that appeared on the last page. Designed as a parody of centerfolds in adult magazines and advertisements, the fold-in was an illustration with a question. When folded, it revealed the answer in an altered image.

“If they’re doing all of these sumptuous fold-outs, Mad ought to do a cheap, black-and-white fold-in,” he said. In 1964, he pitched his first fold-in to editor Al Feldstein and publisher Bill Gaines, thinking that it was a one-time thing. They loved it enough to make it a regular feature for the monthly magazine.

As I grew in my observance, the magazine was in decline, as it competed against late-night television comics and online humor. In 2001, when Mad Magazine reluctantly accepted advertisements in exchange for color pages, it also became more vulgar and my interest in it diminished. The exception was Jaffee, whose Snappy Answers and Fold-Ins were as timeless as Dave Berg’s Lighter Side, and Antonio Phohias’ Spy vs. Spy.

It was through the Internet that I learned about the Jewish elements of Jaffee’s life and profession. He was born on March 13, 1921, in Savannah as Abraham Jaffee. His parents Morris and Mildred were immigrants from Lithuania with opposite reactions to their experiences in America. His father worked hard as a tailor and rose to become a shopkeeper. His mother kept Shabbos and a kosher home, fearing that their three sons would assimilate and stray from observance.

“My mother took me and my brothers back for a short trip to the town she was born in, in Lithuania,” he said in an interview with The Comics Journal in 2000. “Well, the short trip took four years, and all that while I wrote desperate letters to my father in New York and told him how much my brother Harry and I missed our comics. So, he started sending them to us.”

The village of Zarasai was in an isolated corner of the country, near the present-day borders of Latvia and Belarus. He described the conditions as “19th century,” exacerbated by the Great Depression. With support from his father, he was more fortunate than most of the shtetl dwellers. At age 12, his father sent for him to return to America. His mother stayed in the alte heim and became a victim of the Holocaust.

When the High School of Music and Art opened in 1936, he was among its first students. Among his classmates was Harvey Kurtzman, who was a founder of Mad. Although most of his colleagues were also Jews, with varying relationships towards observance, Jaffee did not express openly Jewish themes in his illustrations.

Typical of the American Jewish experience, it was Chabad that inspired Jaffee to publish Jewish content that inspired observance among young readers. A rabbinical student, David Masinter, was working on a magazine for the youth organization Tzivos Hashem in 1983. With the Lubavitcher Rebbe’s blessing, he sought top talent for his cause. “As a kid growing up in South Africa in the 1970s, Mad Magazine was exceptionally popular,” he said in an interview with Chabad.org. “So, I said, we need to get these guys for the Moshiach Times!”

Rabbi Masinter called on Dave Berg, Joe Kubert, and Jaffee to freelance for his magazine. “We were the Rebbe’s emissaries, so we told them what the Rebbe had taught us: ‘G‑d gave you a talent.’ Instead of just making people smile, use it to really help uplift the world.”

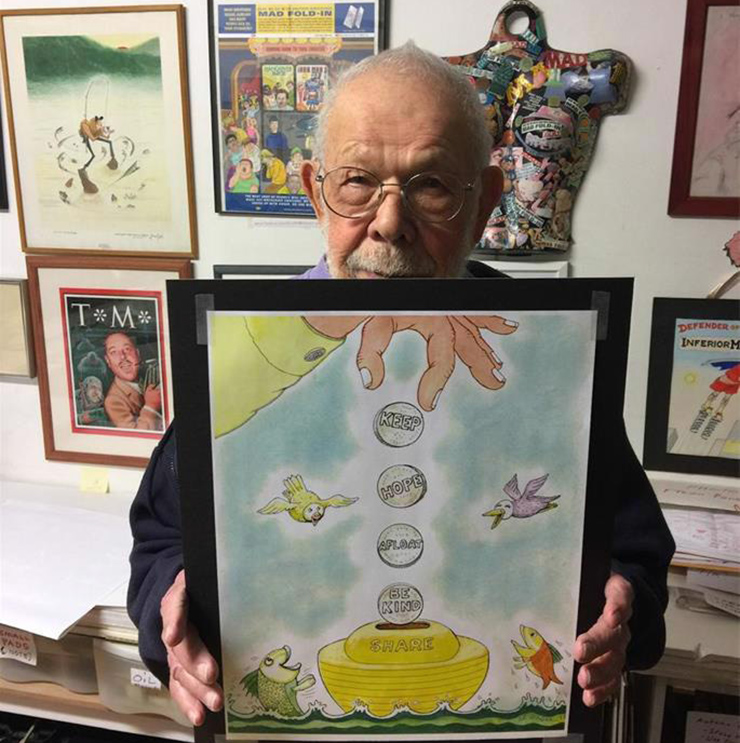

Jaffee opened up to Masinter about his childhood in Lithuania and how it related to his art. “In cheder, we learned about various stories from the Torah. I was fascinated by the story of Noah’s Ark. So, I carved an ark out of wood with little animals that could stand around it.”

Rabbi Dovid Shalom Pape, the editor of Moshiach Times, brought mezuzos to Jaffee, wrapped t’filin on him, and provided for Kaddish in memory of Jaffee’s wife Joyce.

“I enjoy working on ‘the Shpy,’” Jaffee said of his superhero character in Moshiach Times. “Not like Superman or some other hero, he’s someone the kids can relate to. He stands up to the Hamans and the bad guys of the world, protecting Jewish children.”

In 2019, Mad Magazine published its final monthly issue, shortly after Jaffee’s retirement. He was a witness to the prewar shtetlach, the golden age of American Jewish comedians, the rise and decline of a popular humor magazine, the inspiration for many comedians, comic artists, and commentators. I was born in Latvia and loved his illustrated depictions of society. I attended the same art school as Jaffee under its later name, LaGuardia High School.

This past Pesach, in honor of this favorite artist, my daughter made puns, shared her own margin caricatures in a class Haggadah, and then we made up our own “Snappy Answers to Stupid Questions.” His memory lives on.

By Sergey Kadinsky