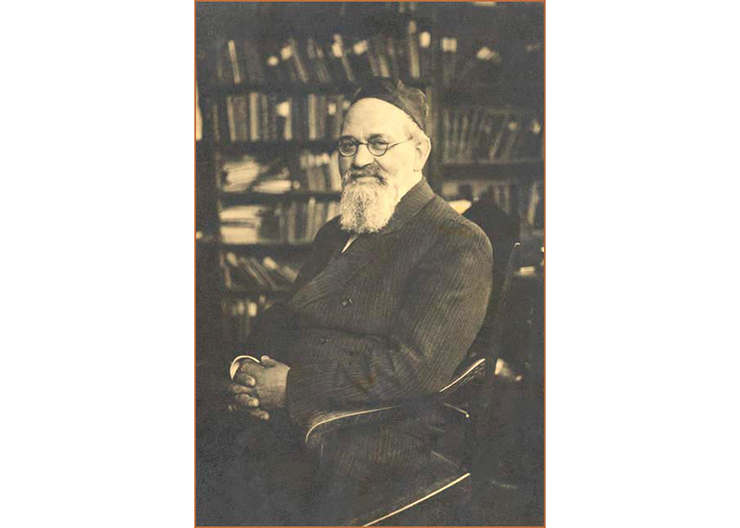

Returning to my childhood neighborhood, it is easy to see how much things have changed. The massive reconstruction of the Beth Gavriel synagogue in Forest Hills continues, as its exterior receives a palatial look and a dome. Inside, the labyrinth of hallways and stairs have not yet been altered. On the second floor, a set of rabbinic portraits on the wall lead to the beis k’neses and the office of Rabbi Emanuel Shimonov, the Rav of Beth Gavriel.

I sought to interview him on the occasion of his 30th anniversary since he immigrated to Queens with his wife Esther and four children. The exact date of his arrival is unclear, depending on how one defines it. “I was born in 1961 in Samarkand,” he said. “When I was born there were no Jewish schools. Only one of the 25 synagogues was open. It had more than 50 sifrei Torah.”

Rabbi Shimonov’s parents were religious, keeping a kosher home in a society where religious observance was discouraged by authorities, and there were no opportunities to openly teach Judaism. The visit to the historic Gumbaz synagogue inspired the young Shimonov to consider a much larger religious community that was forced to consolidate into one building.

“In Penjikent, there was Rav Hiskia Sezanaev. I was four years old. He took me to his cheder. It was an underground yeshivah. I learned there and my parents didn’t know,” he said. “Initially I learned for one hour, then after six months it increased to three hours. We learned Torah, Rashi, and Gemara.”

This underground cheder operated under a method created by Chabad to spread Jewish teachings across the Soviet Union. “It was a group of ten who, in turn, each taught ten men in basements and attics.” Among his teachers was Rabbi Daniel Shakarov, a talmid of Chabad shliach Rabbi Shlomo Leib Eliezrov, who settled in Samarkand in 1890, ensured that the mikvah and meat were kosher, and taught his students how to do sh’chitah.

In the early Soviet years, Rabbi Shakarov operated a yeshivah. When it was closed by the government in 1930, he took the classes underground, continuing to educate generations of Bukharian youths during the Soviet period.

Rabbi Shimonov shared the book Defiance in Samarkand by Rabbi Shlomo Chay Niyazov of Borough Park, which provides a detailed account of Chabad’s role in secretly educating Bukharian Jews during the Soviet period.

“When he died, I moved to Tashkent and learned with Rabbi Moshe Aron Geisinsky. Then I served as a shochet and mohel.” He davened at the Or Avner synagogue, which reopened in 1986 and was led by Rabbi Shakarov, who lived next door to it.

When Soviet leader Mikhail Gorbachev announced the glasnost policy in 1986 allowing for freedom of expression, Jews across the country reopened synagogues, yeshivos, and Hebrew classes.

“Our house was open to all, where we discussed Jewish questions and learned with people. I received and distributed matzah from Israel, America, and Moscow. It was very important to have matzah for Pesach,” he said. “We had 650 students in the Jewish school. Half of the day was devoted to secular subjects, and half to religious instruction. We received support from around the world. We had a kollel, ulpan, and glatt kosher meat.”

When the Soviet Union broke apart in 1991, Uzbekistan declared independence and its storied Bukharian Jewish community was apprehensive about economic uncertainty, the civil war in neighboring Tajikistan, and antisemitic incidents, many immigrated to Israel, the United States, and Austria. With their country open to the world, Bukharian Jews learned about economic and religious freedoms in the West.

“People left Samarkand quickly, as teachers told us about the world. At the airport, we took down their future addresses so that children would immediately attend yeshivah in their new homes.”

As many of his neighbors and students were making the move, his family followed in 1994. Upon landing in Queens, he was invited by Rafael Normatov to be the mohel for his son’s bris milah on that day, with accomplished musician Avraham “Avrom” Tolmasov serving as the sandak.

However, as the Chief Rabbi of Uzbekistan, Rabbi Shimonov had many responsibilities in the old country: performing bris milah, weddings, funerals, kosher supervision, and the upkeep of synagogues and cemeteries. A month after arriving with his family in New York, Rabbi Shimonov flew back to Tashkent to perform his communal duties.

“It was very difficult and tiring to fly back and forth,” he said. On the ground in Uzbekistan, he then traveled to perform bris milah and shechitah in Kattakurgan, Hatyrchi, Paishanbe, Shahrisabz, and other cities.

“I asked my family to stay in America and I returned to Tashkent where I continued to serve for three years,” he said. “It was difficult. My family said either you come to us or we go to you. They said that they couldn’t live there, so after one more month after a successor was selected, I returned to America.”

With the support of philanthropist Lev Leviev and Chabad, Jewish education and rituals continued to be practiced in Uzbekistan, even as the community declined and aged.

“I studied for a year in kollel, and a year later Beth Gavriel was founded. “We initially rented space inside an Ashkenazi yeshivah, and then the synagogue owned this building.”

The sound of children going to class is heard outside Rabbi Shimonov’s office as Beth Gavriel is more than a synagogue. It hosts the Yeshiva Sha’arei Zion High School, along with learning for adults from morning to evening every day. Since 1997, new Bukharian synagogues and schools have opened across Queens, the suburbs, and other states.

When Bukharian Jews return to 108th Street to shop, celebrate simchos in nearby catering halls, and visit family members, they pass by Beth Gavriel and recall that for many in the community, this is where their American lives began, where their Jewish observance was restored, and it remains a thriving institution.

Among its congregants are children of immigrants who succeeded in their careers and personal lives. Under the guidance of Rabbi Shimonov, Chazan Ezro Malakov, Rabbi Israel Itshakov of the second-floor youth minyan, and its distinguished board, Jewish leaders emerged from this k’hilah, such as brothers Ruben and Shimon Kolyakov of Torah Anytime, and Rabbis Ilan and Yaniv Meirov of Chazaq, among other organizations.

“This shul is the most open to events and shiurim. This is the reason for their success,” said Rabbi Yaniv Meirov. He spoke of how Rabbi Shimonov encouraged more minyanim in the building, such as the youth minyan, netz minyan, and a morning kollel.

“Beth Gavriel hosts the Chazaq Tish’ah B’Av marathon. He is always encouraging Chazaq to do more and directs students to be involved with Chazaq.”

Rabbi Itshakov was involved with Beth Gavriel for only a year longer than Rabbi Shimonov, when it had just one minyan renting space inside the building. “A lot of things happened,” following his arrival to the community. “We purchased this building and the Sha’arei Zion building.”

As the main rabbi of Beth Gavriel, he leads the minyan in the main hall, conducts bris milah, weddings, funerals, and speaks at yushvo gatherings (the memorial meals that are customary in the Bukharian community). Speaking Russian and Bukhori, he attracts older congregants back to observance, while encouraging younger members to do right by their fellow Jews. As the honorary president of the Samarkand Fund, Rabbi Shimonov coordinates efforts to preserve the historic Gumbaz synagogue and Jewish cemetery in his birthplace city, with the cooperation of local authorities.

The ongoing reconstruction of Beth Gavriel will expand its capacity for prayers, social functions, and classes, along with the completed mikvahs and library.

“What nobody else can do is that when a husband doesn’t want to give a divorce, he has ways, nonviolent, to find a way to convince the man,” Rabbi Itshakov said. “He can do it, and I personally know ten such cases.”

In an interview with Veliyam Kandinov of the Bukharian Jewish Link, Rabbi Shimonov spoke of efforts to preserve shalom bayis among couples in his community.

“Men should not have illusions that the material well-being they create for the family is the only condition for spiritual closeness and mutual understanding with the wife. A man’s courtesy and attention towards his wife, a kind word or a tender compliment are very often incommensurate with the wealth of the house and the most prestigious car, bought as a gift for his beloved woman,” he said. “It is not for nothing that it is generally accepted that ‘a woman loves with her ears.’”

“So much has to be done here. We need more synagogues. If there are 500 people in each one, that’s only 20,000 people attending services. We have more than 90,000 Bukharian Jews in America,” Rabbi Shimonov said. On the wall behind his chair is a photo of Israeli Sefardi Chief Rabbi Shlomo Amar and philanthropist Simcha Elishaev. He spoke of Rav Ovadia Yosef zt”l, known as the Maran, or master, who led a religious revival and political awakening among Sefardi and Mizrachi Jews in Israel, and its parallels among Jews in Queens.

“We need to restore the crown,” quoting the Maran.

By Sergey kadinsky